In 2010, the small community of specialists who pay attention to US road safety statistics picked up the first signs of a troubling trend: more and more pedestrians were being killed on American roads. That year, 4,302 American pedestrians died, an increase of almost 5% from 2009. The tally has increased almost every year since, with particularly sharp spikes in 2015 and 2016. Last year, 41% more US pedestrians were killed than in 2008. During this same period, overall non-pedestrian road fatalities moved in the opposite direction, decreasing by more than 7%. For drivers, roads are as safe as they have ever been; for people on foot, roads keep getting deadlier.

Through the 90s and 00s, the pedestrian death count had declined almost every year. No one would have confused the US for a walkers’ paradise – at least part of the reason fewer pedestrians died in this period was that people were driving more and walking less, which meant that there were fewer opportunities to be struck. But at least the death toll was shrinking. The fact that, globally, pedestrian fatalities were much more common in poorer countries made it possible to view pedestrian death as part of an unfortunate, but temporary, stage of development: growing pains on the road to modernity, destined to decrease eventually as a matter of course. The US road death statistics of the last decade have blasted a hole in that theory. (A similar trend has been observed with regards to the country’s cyclists: a recent analysis found that cyclist fatalities decreased through the 80s, 90s and 00s, but since 2010 have increased 25%, with 777 cyclists killed in 2017.)

Trouble, albeit of a less dramatic sort, has also been brewing in the UK and western European countries, long seen as bastions of pedestrian-friendly (and cyclist-friendly) conditions. Through the 70s and 80s, these countries’ fatality rates were just as bad as America’s, or worse. But, since then, their progress has been more substantial and more enduring. The problem is that, since 2010, that progress has mostly sputtered to a halt. In general, the fatality numbers are not going down. “There’s immense frustration,” says Philip Gomm, of the RAC Foundation, a UK organisation that studies road safety issues. “Things were getting better, and now they’re not.”

In almost every country in the world, regardless of national prosperity, it remains on average more dangerous, per mile of travel, to be a pedestrian than to be a car driver or passenger. Worldwide, more than 700 pedestrians die every day, disproportionately in poorer countries. At least four times that number are seriously injured. We talk a great deal about how cars congest our cities and pollute the atmosphere. We talk less about how they keep killing and maiming people simply trying to get from A to B on two feet.

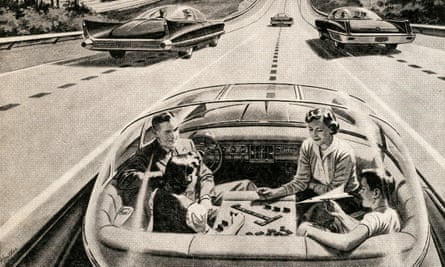

Lately, our cultural conversation about road safety has been dominated by visions, sold by Silicon Valley, of vehicles that minimise or even eliminate the need for input from a fallible human driver. Every year, more cars come armed with “pedestrian detection and avoidance” systems; soon, these systems will likely be standard issue. And not long after that, we are promised, sensors and self-improving algorithms will take over the driving process altogether, eliminating human error from roads and ushering in a new golden age of safety for all their users, whether or not they’re cocooned by a car’s steel frame. Since 2017, General Motors, the US’s largest car manufacturer, has claimed that it is developing self-driving vehicles in the service of a “triple-zero” world: zero crashes, zero emissions and zero congestion.

The possibility of making pedestrians safer is a welcome one, not least because walking is so undeniably good. Walking boosts physical and mental health, draws communities together and produces no carbon emissions. But there are good reasons to be sceptical about the promises made by the proselytisers of the high-tech car future. Car companies swear they are here to help – by selling us products that hardly ever hit anyone or anything. But the truth is that this promise is, at best, a distraction. In fact, much of our discourse around cars, self-driving or otherwise, is less about transforming the status quo than maintaining it, obscuring paths to progress exactly when we need them most, and leaving pedestrians right in the line of fire.

Ask a room full of road safety experts what is causing pedestrian fatalities to increase and most will admit that, well, they are not exactly sure. Every time a car hits a pedestrian, it represents the intersection of a vast number of variables. At the level of those involved, there is the question of who is distracted, reckless, drunk. Zooming out, there are factors such as the design and condition of the road, the quality (or absence) of a marked pedestrian crossing, the speed limit, the local lighting, the weight and height of the car involved. In a crash, all these variables and more converge at high speed in real-world, non-laboratory conditions that make it hard to isolate the influence of each variable.

Attempting to explain a trend – to correctly apportion blame not for one but thousands of pedestrian deaths – adds yet more layers of complexity. Economic and employment trends, the availability and quality of public transport, shifts in the age of walkers and drivers: it all matters. Disentangling the threads in a scientifically rigorous way is fiendishly difficult. “There are multiple theories about how to account for what is happening,” says Norman Garrick, a University of Connecticut professor who studies road safety. “We know something radically new is going on. But I don’t think we have an exact answer yet.”

Ask that same room of road safety experts a slightly different question – not exactly why US pedestrians fatalities have risen lately, but instead why the US has more of them than any other wealthy country – and the answers will come flooding out. In recent months, after conversations with more than a dozen such experts, I became familiar with a particular tone of voice: deep frustration at how obvious it all is, but wrapped in a package of professional cheeriness. “Well, where to start?” says Eric Dumbaugh of Florida Atlantic University. “So much of it is relatively simple, which makes the lack of progress that much more aggravating.”

Here is what the frustrated safety experts will tell you: Americans are driving more than ever, more than residents of any other country. More of them than ever are living in cities and out in urban sprawl; a growing number of pedestrian fatalities occur on the fringes of cities, where high-volume, high-speed roads exist in close proximity to the places where people live, work, and shop. Speed limits have increased across the country over the past 20 years, despite robust evidence that even slight increases in speed dramatically increase the likelihood of killing pedestrians (car passengers, too – but the increase is not as steep, thanks to improvements in the design of car frames, airbags and seatbelts). American road engineers tend to assume people will speed, and so design roads to accommodate speeding; this, in turn, facilitates more speeding, which soon enough makes higher speed limits feel reasonable. And more Americans than ever are zipping around in SUVs and pickup trucks, which, thanks to their height, weight and shape are between two and three times more likely to kill people they hit. SUVs are also the most profitable cars on the market, for the simple reason buyers are willing to pay more for them. As with speeding, there appears to be a self-perpetuating cycle at work: the increased presence of large cars on the road makes them feel more dangerous, which makes owning a large car yourself feel more comforting.

More fundamentally, the US is the country in the world most shaped, physically and culturally, by the presumption that the uninterrupted flow of car traffic is an obvious public good, one that deserves to trump all others in the road planning process. Many of its younger cities are designed almost entirely around planning paradigms in which pedestrians were either ignored or factored only as nuisances. Cars move fast and are heavy and hard; humans on foot move slower and are made of flesh and bone. “The layperson can realise, if they think about it for a minute, that if you want to keep people safe, you have to design streets differently,” says Dumbaugh. “You have to slow the cars down. You have to recognise the reality of road users who aren’t in cars. You have to design roads so people in cars take notice of their fellow road users. But these basic realisations aren’t things the US transportation system knows or integrates into practice. And so people keep getting killed.”

While safety experts tend to focus on broad factors – the road environment and what types of behaviour it encourages – America’s cultural discourse on road safety tends to go in the opposite direction, zooming in on that most American of variables: the individual. It is not cars, car culture or bad, car-centric planning that kill pedestrians. Instead, it is individuals making bad choices about how to use the roads.

There is no greater symptom of this worldview than the recurring focus on mobile phones, especially smartphones and their tendency to monopolise our limited attention. Road signs warning against phone use while driving are so commonplace that they almost blend into the landscape. Parents make their kids promise they won’t use their phones while driving. Kids nod and promise they won’t. Phone-tracking studies indicate that most of them do it anyway and that their parents do, too.

In recent years, America’s fear of the distracted driver expanded to include the distracted walker. This is a replay of an old phenomenon: it was the US that invented the concept of the “jaywalker”, a “jay” being an unsophisticated person from the country who did not even know how to walk correctly. In the US, much like anywhere that cars have taken hold, drivers screaming at pedestrians (and cyclists) that they are doing it wrong is a fixture of national life. More recently, numerous states and cities, including San Francisco and New York, have launched public campaigns against inattentive walking, as has the US National Safety Council. Some jurisdictions have passed, or sought to pass, bills that would make using a smartphone while crossing the road an offence punishable by fine. On Twitter, the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has weighed in on the pedestrian safety crisis primarily by coaching pedestrians on how to protect themselves. “When you are walking, be predictable”, advises @NHTSAgov.

Ask a room full of safety experts about smartphones and you will get a mix of resignation, bemusement and contempt. “I tend not to buy the smartphone distraction stuff,” says Garrick, echoing nearly identical comments from just about everyone I talked to. “To me, it reads as shoving aside actually dealing with the relevant issues.” What particularly bothers him, he says, is how poorly thought out the distraction discourse tends to be. In the UK, Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Austria and Iceland, for example, pedestrian deaths occur at a per capita rate roughly half of America’s, or lower. Are we really to believe that the citizens of these countries are 50% less susceptible than Americans to distraction, by their phones or anything else? Plus, within the US, pedestrian death occurs disproportionately in neighbourhoods populated by people with low-incomes and people of colour. Is distraction really more endemic in those neighbourhoods, or among people driving through them, than it is in wealthier, whiter areas? Or is it more likely that these neighbourhoods are more likely to be criss-crossed by high-speed roads, and less likely to receive investment in transit interventions that protect pedestrians?

“All this talk about pedestrian distraction, driver distraction? It’s such a distraction,” says Ben Welle of the World Resource Institute for Sustainable Cities. “It puts all the responsibility on individuals, and none on the environment they operate in.”

Over the past decade, as the American pedestrian’s plight has worsened, global car manufacturers have stepped forward with news of a supposedly game-changing innovation, one that might at last improve the fate of those who want to travel on foot. This innovation has nothing to do with re-engineering roads, regulating SUV design, investing in public transit or any other intervention that would require using the creaky levers of democratic politics. Instead, people just have to buy new cars.

In spring 2010, Volvo announced what sounded like the inauguration of a new era, one in which cars at last acknowledged pedestrians. Starting that autumn, anyone who bought a Volvo S60 saloon could, for an extra $2,100 (£1,700), have it equipped with Pedestrian Detection, a radar-and-camera-based system designed to sense the presence of pedestrians in the car’s path – and, if needed, automatically brake to avoid hitting them. An older variety of sensor, made available in 2005, had equipped some cars to sense pedestrian collisions while they were in progress and, in response, pop up their hoods a few inches, creating a “crumple zone” between the bonnet and the hard machinery inside, making for a softer landing. But these systems had been sold only in Europe, and they did nothing to stop cars from hitting pedestrians in the first place, or slow them down in advance of the collision.

Every year since Volvo Pedestrian Detection arrived on the market, systems like it – like all “assistive driving” features – have become more sophisticated and more common. As of last year, pedestrian-sensing technology is now standard on close to a third of new vehicles sold in the US, and available as an add-on for another third. In the EU, regulations passed earlier this year will make such systems mandatory on new cars starting in 2022. Their growing popularity is largely attributable to the relevant tech getting cheaper, but endorsements from trusted institutions have also played an important role. Since 2016, Europe’s New Car Assessment Program, which issues influential annual rankings of vehicle safety, has awarded extra points to cars with pedestrian detection and avoidance systems. In the US, the well-respected Insurance Institute for Highway Safety has advocated the widespread adoption of pedestrian avoidance tools. Just this year, the nationally venerated American buyer’s guide Consumer Reports announced that, for the first time, it would factor pedestrian avoidance into its ratings, in hopes of incentivising carmakers to help address rising pedestrian fatalities.

At first glance, this all sounds like a long-overdue corrective to the car-first chauvinism that has made American roads so deadly. But none of the safety experts I spoke to were terribly excited about pedestrian avoidance technology. It wasn’t that they doubted it might save some pedestrian lives. Instead, their recurring concern was that it reflects an ongoing focus on individual shortcomings – on flawed drivers and walkers – and a neglect of flaws built in to the roads they are forced to use.

“Pedestrian detection will probably help a bit,” says Dan Albert, author of Are We There Yet?, a history of American car culture. “But at the same time, it’s pretty clear that these problems can be addressed without hi-tech solutions. And so what are the car companies up to? It’s not just about some altruistic desire for safety, or they would be including these systems on all of their cars, which very few companies are doing. It’s more about creating a range of products that allows them to maximise profit.”

Recent studies have found that high percentages of drivers do not understand exactly what these new systems do. I recently rented a car armed with sensors to help you stay in your lane, sensors to detect other cars and sensors to detect pedestrians; for four days I drove around not knowing to what extent each of these systems was switched on or what they did, exactly. Studies of car dealerships have found that many people selling these systems are not much better informed than I was; in 2015, a video that went viral in the online car world showed a salesperson behind the wheel of a Volvo X60 driving into a crowd of customers; he was demonstrating the car’s City Safety system, but he had failed to understand that, unlike other Volvo safety systems, the one he was showing off did not include pedestrian detection. (None of the people hit were seriously injured.)

Of course, people can learn to understand new tools. More troubling is the fact that very little robust evidence has been available as to pedestrian avoidance systems’ real-world benefits. The organisations rating these systems do so based on tests conducted in laboratories and on test tracks, but it has not yet been reliably established how well these tests predict performance on actual roads, with real live pedestrians instead of crash test dummies (not to mention variable light and rain conditions).

“These technologies are still very much in their infancy,” says Laura Sandt, a pedestrian safety expert at the University of North Carolina Highway Safety Research Center. In the US, pedestrian avoidance systems are rated by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. The organisation, Sandt explains “is only able to test effectiveness in very specific conditions. One big example is that, in their tests, the vehicles are always going straight. But we know that a huge number of pedestrians are hit by vehicles that are turning. We have no way of knowing how well the tests line up with real-world conditions.”

In the US, almost every article about pedestrian avoidance systems cites a single real-world impact study, holding it up as evidence that such systems could decrease pedestrian collisions by 35%. This study is the best one available, for the simple reason that it is the only one available. This makes its weaknesses all the more glaring: it considers only one system, the Subaru EyeSight, and uses a severely limited methodology that – as the study’s authors acknowledge but press coverage never does – meant the authors could not know for sure that they were accurately counting the total number of times Subarus hit pedestrians. No one can honestly claim to know how well these systems do what they claim. A 2018 study concluded that, when it came to simply detecting pedestrians (let alone avoiding them), these systems would have to improve their performance tenfold just to match that of humans.

Plus, as several of the experts I spoke to reminded me: every year since 2010, cars with pedestrian avoidance systems have represented a higher proportion than ever of cars moving around on American roads. And almost every year since 2010, the pedestrian death count has gone up.

The origin story of pedestrian avoidance systems has almost nothing to do with a desire to protect pedestrians. Instead, they grew out of a desire to make war more bloodless – or more bloodless for the US side, anyway. In 2004, the US Department of Defense announced a race, open to all comers. Entrants were asked to build a vehicle that could undertake a journey without immediate human input: no driver in the car, no remote control. Whoever’s vehicle made it through a 150-mile course in the Mojave desert first would win $1m.

For years before the race, the military had been trying and failing to create unmanned vehicles to minimise the loss of life along battlefield supply routes. The widespread use of improvised landmines in post-9/11 warzones had only increased the urgency. The DoD races (there was a desert sequel in 2005 and a San Francisco-based contest in 2007) attracted teams of the world’s brightest and most ambitious engineers and programmers, focusing their energy on a new goal to which very few people had given much thought before.

It was all this excitement among techies that put the idea of driverless vehicles on Silicon Valley’s radar. In 2009, when Google launched its self-driving car lab, it was staffed almost entirely by participants in the military contests. Like the US military, tech conglomerates had a specific motive for developing these cars. Again, the central concern was not road safety, let alone pedestrian safety. In several industries, from taxis to long-haul transport, one of the major costs is the need to pay human drivers, plus to reckon with those drivers’ human limits, such as the need for sleep and bathroom breaks. By removing the need for humans, and providing the replacement at a lower cost, tech firms stood to reap big profits – especially if the new vehicles relied on wireless internet connections, served as streaming entertainment stations for their passengers, and generated gigabytes of harvestable data per journey. For some transport companies, such as Uber, self-driving vehicles are a cornerstone of their long-term plans. One reason that Uber has never turned a profit is because of the cost of paying human drivers. The company believes that if it can win the race for self-driving technology, it will finally be in the black. Since 2016, it has invested more than $1bn towards achieving this goal; this April, its self-driving team secured another $1bn in investments from Toyota, SoftBank and the Japanese carmaker Denso.

Of course, in time-honoured Silicon Valley tradition, this simple profit motive was quickly swaddled in all manner of high-flying rhetoric about saving lives (of car users and pedestrians alike), saving cities and transforming transportation as we know it. “Every year that we delay this, more people die,” Anthony Levandowski, then of Google, told the New Yorker in 2013. At a 2016 press event, Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla, warned journalists who expressed doubts about self-driving cars – like the type that Tesla plans to sell – that they had blood on their hands. “If, in writing something that’s negative, you effectively dissuade people from using an autonomous vehicle, you’re killing people.”

“There is simply a very good business reason for car companies to sell people a future where everything is better, especially when the way to get there is by purchasing a lot of cars,” says Peter Norton, perhaps the most prominent historian of how Americans think about traffic safety. As Norton pointed out, car manufacturers have long made a practice of stoking consumer dissatisfaction, and yoking it to utopian visions of the future in which cars of the future solve problems created by cars of the present. “I don’t think there’s any chance that autonomous vehicles will deliver us a safe future, and I don’t necessarily think the companies think so either. I think they think we’ll buy a lot of stuff. The safe future will recede before our eyes like a desert mirage.”

The self-driving car “space” is flooded in loose cash. This is why pedestrian avoidance systems are becoming ubiquitous. Investment dollars have both improved the required parts and programmes and pushed down their cost. Otherwise, they would not be affordable enough to sell to any but the richest car-buyers. Meanwhile, the race continues. The tech companies keep saying they are almost there (they know they said they were almost there before, but this time is different, they promise). Almost every major car company has partnered with a lab developing self-driving car technology, either because they think it might become a requirement to stay in business, or because enough of their shareholders think so that they need to make a show of playing along.

All this activity – and the rollout of shiny pedestrian avoidance systems – feeds more credulous media coverage, stoking our cultural sense, unsupported by any evidence, that of course our hardworking nerds are on the brink of unveiling safe self-driving cars. Why not? A car that is basically a smartphone will, of course, have no temptation to look at its smartphone.

One night in March 2018, a 49-year-old woman named Elaine Herzberg was pushing a bicycle laden with grocery bags across a four-lane road in Tempe, Arizona when she was struck and killed by a Volvo X90 operating under the control of Uber’s self-driving software. As is standard practice, a backup safety driver, employed by Uber, was sitting in the car, the idea being that she would take over in the case of error. 1.3 seconds before impact, Uber’s software calculated that emergency braking was called for. According to Uber, self-braking had been turned off to reduce jerky and unpredictable behaviour. With less than a second to go, the safety driver tried––and failed––to swerve away. (The post-crash investigation indicated that she had probably been watching the singing contest The Voice on her phone.) News outlets around the world covered Herzberg’s death in obsessive detail, asking whether it indicated that autonomous vehicles were less “ready” than we had been led to believe.

But, just as the original quest for autonomous vehicles had nothing to do with pedestrian safety, concern over Herzberg’s death often felt curiously divorced from concern for pedestrians in general. Herzberg was killed in March 2018. Between January and June of that year, 124 pedestrians were killed in Arizona, more than all but four other states in absolute terms, and more than all but one on a per capita basis. It goes without saying that none of these pedestrians’ names are known around the world, or that any of them generated a slurry of commentary about whether the American transportation environment is “safe enough” or “as safe as it should be”.

The sight, to our contemporary eyes, of a car navigating without a human behind the steering wheel, is so viscerally strange – so sci-fi – that it can obscure the extent to which a self-driving car remains … a car. Engine, seats, wheels. Similarly, our contemporary sense that hi-tech disruption comes for all things can obscure the extent to which the world promised by autonomous cars is still a world full of cars. To the extent that the world’s roads and cities remain shaped around the worship of smooth car traffic flow, the laws of physics will continue to make them dangerous places for everyone, especially those not protected by a steel frame and airbags.

The problems of car culture and car-centric planning – with its hostility to an activity as beneficial and simple as walking around – are an American gift to the world, but unfortunately they are not exclusively American problems. Worldwide, urbanisation and car ownership are on track to increase massively in coming years. One in three new cars sold globally are SUVs or “crossovers”: smaller SUVs that get better fuel economy but replicate many of the hazards to pedestrians. To the extent that poorer countries building new roads follow traditionally American models of street planning, pedestrians will continue to be the most vulnerable road users in the world. And to the extent that self-driving car hype influences thinking on the future of road safety, the debate will remain muddled.

“Let’s say these cars are going to be the miracle solution,” says Etienne Krug, a Belgian epidemiologist who works on road safety for the World Health Organization. “I think it’s very naive to think so – but maybe. Even if they were ready tomorrow: it takes a long time for the fleet of vehicles on the road to get totally replaced. Let’s say it takes 10 years. What are we supposed to do in the meantime? Let millions of people die on the road? And then what if the miracle solution never comes? We need to assume it won’t.”

“People in the international road safety community aren’t running around incredibly excited about autonomous vehicles,” says Ben Welle. “We don’t know if they’re going to work, or when they’re going to work. And meanwhile we know what we can do: we can get over this idea that we must engineer unending car flow. And we can do that now. And we need to do it no matter what happens with autonomy. An unending flow of autonomous cars is just as bad. And that could happen if we’re not careful.”

In the UK and western Europe, the question of whether pedestrian fatality numbers can once again decline may depend on political will, which varies from country to country. In Sweden, for example, stagnating pedestrian death numbers have been a cause for immense concern from the country’s safety officials, who have committed to doing whatever it takes, including developing new street surfaces that are softer for pedestrians to fall on, and even banning cars from the core of major cities.

In the UK, by contrast, the coalition government formed in 2010 opted to no longer set goals for road casualty reductions of any kind, because setting goals meant the possibility of admitting failure; no new national targets have been set since, which safety advocates point to as part of the reason for the lack of progress. “We picked off a lot of the low-hanging fruit,” says Joshua Harris of Brake, a UK road safety charity. “And now it’s the difficult decisions that need to be made, decisions about whether we’re going to fundamentally reshape the landscape to be a place where everyone can travel in a safe and healthy way.”

In the US, meanwhile, it remains the case that pedestrian advocates have failed to engineer the cultural process that transforms a scattered mass of dead and injured bodies into a widely recognised problem. They have not come close. When two Boeing 737s went down, killing 346 people, it triggered multiple government investigations. Crash reconstruction and analysis experts showed up. Corporate spokespeople apologised, began handing out cheques to victims’ families and swore to do better. Journalists searched for explanations. But cars kill a 737’s worth of American pedestrians every couple of weeks. Internationally, it is more than three 737s per day. And the news cycle barely stutters.

In 2017, for the first time, each US state was required to submit road fatality reduction targets to the federal government. Most states set extremely limited goals: Wisconsin, for example, aimed to have 342 pedestrian fatalities, instead of 361. Several set a rather fatalistic goal of no reduction at all. Eighteen states went a step further, setting as their target an increase in their pedestrian death count. It is not that they want more pedestrians to die. But they know that people are likely to be driving more, they know what their roads are like and they know the laws of physics. Unlike the unending stream of hype coming from the autonomous car sector, these dour projections received no coverage outside of traffic reform circles. Unfortunately, they are more likely to contain the truth.

This article was amended on 3 October 2019 to clarify the sequence of events before the fatality in Tempe, Arizona.