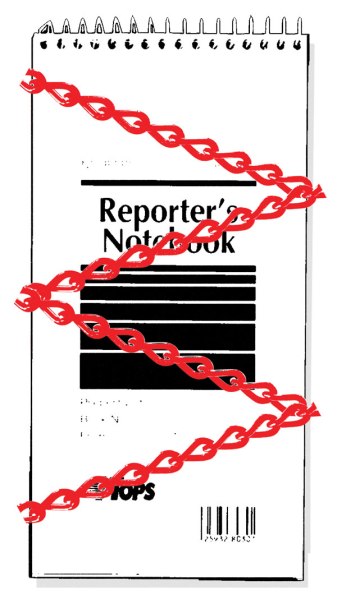

In May, news broke that our government had obtained—without a warrant—copies of phone records of the Associated Press offices in New York, D.C. and Connecticut, as well as reporters’ private lines. When I heard that, I was prompted to look up some easily obtainable data of my own: How many journalists are working in America, and how many Americans have security clearances?

In May, news broke that our government had obtained—without a warrant—copies of phone records of the Associated Press offices in New York, D.C. and Connecticut, as well as reporters’ private lines. When I heard that, I was prompted to look up some easily obtainable data of my own: How many journalists are working in America, and how many Americans have security clearances?

There are about 65,000 journalists working for brands of one sort or another, according to a report in the Nieman Journalism Lab. And 5 million Americans now hold a security clearance.

In other words, there are about 77 people keeping secrets about the government for every single person whose professional duties might include asking questions about that government.

Since the revelations about the warrantless requisitioning of the AP’s calls, this problem has only grown more troubling. We’ve learned about the scale of the surveillance, and we are beginning to see just how far the state will go to protect itself from tough questions.

Besides Ed Snowden’s confirmation of every paranoid suspicion about Big Brother, down in Texas, another skinny white guy about the same age sits in a jail cell, awaiting trial. This one, Barrett Brown, is a journalist, and his crime is copying a URL. Mr. Brown did not perform any hacking himself; he merely linked to a site that published emails hacked from a private security contractor, HBGary.

Mr. Brown now faces a rash of charges for publishing sensitive national security material gained by hacking. If convicted, he faces a century in prison.

Journalists have been covering the national security data-mining story as one about privacy, whistle-blowing or President Barack Obama. Fewer are asking what the new age of surveillance means for the men and women tasked with maintaining the transparency on which democracy depends.

The technology that enables the programs Mr. Snowden revealed has already completely changed the business of newsgathering. The founders of the national security state more than 50 years ago would have had wet dreams about a day like today, had they been able to imagine one.

In the early days of the CIA, the agency itself was still off the books and spy-bureaucrats like Cord Meyer were tasked with infiltrating the intelligentsia the old-fashioned way. In Cold War Washington, journalists like Ben Bradlee and the Alsop brothers were practically on the agency payroll.

In 1969, when military analyst Daniel Ellsberg brought the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times, that all changed. The Nixon government challenged the Times, a case went to the Supreme Court, and journalists won. Mr. Ellsberg, the whistle-blower, survived too, although not for his adversaries’ lack of trying. Among other efforts, Nixon’s henchman G. Gordon Liddy supposedly hatched a failed plot to dose Mr. Ellsberg’s soup with LSD before a major speech so that he would look deranged and discredit himself.

So what’s a little email snooping in comparison?

Mr. Brown is a Texas-based writer perched on the outer edge of what may someday be the new mainstream: self-branded, mouthy and borderline law-breaking journalism. He doesn’t have a Times or Washington Post email address or a CNN pedigree.

He has worked for Vanity Fair and The Guardian, and he got himself a six-figure book deal. He has also worked “the other side” as spokesman for “hacktivist” collective Anonymous.

And he does things mainstream journalists mostly don’t do, calling an enemy “a degenerate pussy” on YouTube and threatening to kill federal agents.

The federal government arrested Mr. Brown last year for disseminating some 70,000 emails that showed, among other things, how that national security data collection has been put to use. Among the creepier initiatives are fake social media personas that robo-spy on dissident individuals and groups, as well as influence public opinion.

But we don’t know what else is in those emails, because Mr. Brown is in jail and his project to analyze the reams of hacked information is dormant.

Lawyer Charlie Swift, known for taking on the government over Guantanamo and representing Osama bin Laden’s driver/bodyguard, is representing Mr. Brown.

“The heart of the case is linking to something,” Mr. Swift said when he took the case. “Classified, secret information held by the government is public property, and, if it’s leaked, the press has the right to publish it. The government now uses private subcontractors to store information, and the question is: Do the same protections apply to private information being compiled for the government?”

This month, the government asked the judge to put a gag order on the Brown case, arguing that the defense was manipulating the media. The defense claims that Mr. Brown hasn’t talked to any journalists, not even to the late Michael Hastings, who was looking at the hacked security emails that were part of Mr. Brown’s project and whose fatal car accident in Los Angeles last month has provoked conspiracy theories.

Whether or not one agrees with Mr. Brown’s style, he is the public face of the 65,000 professional questioners facing off against the 5 million cleared secret-holders in America. He continues to write, and publish, from jail. In July, under a headline “The Cyber Intelligence War and Its Useful Idiots,” he took Tom Friedman to task, pointing out that the columnist’s trust in the government of a dying empire is “misplaced” but acknowledging that half of Americans seem to be equally lulled.

At a fundraiser for Mr. Brown and jailed hacker Jeremy Hammond in Manhattan Monday night, attorney Michael Ratner of the Center for Constitutional Rights said Mr. Brown’s case shows that journalists are the new targets in the government’s effort to protect state secrets. “Brown is in prison for carrying out acts of journalism,” Mr. Ratner said.

While Mr. Brown sits in jail, the journalists who channeled Snowden to the world—Glenn Greenwald and filmmaker Laura Poitras—are also under attack. In a story in last week’s Times, Peter Maas revealed how Ms. Poitras is held at airports and has to stash notes and hard drives in foreign countries and safe deposit boxes. Mr. Greenwald’s partner, Brazilian national David Miranda, was detained at Heathrow Sunday for nine hours, apparently over the Snowden material.

One would think the Poynter Institute, The New York Times and every journalist in the country would be screaming about all of this. On the contrary, there is ominous silence, studded with the occasional attack on rogue disseminators.

This weekend, Time’s Michael Grunwald tweeted, “I can’t wait to write a defense of the drone strike that takes out Julian Assange.” He quickly deleted that ill-considered send, and apologized, but the point was taken. Former Times Executive Editor Bill Keller has made a practice of ad hominem attacks on Mr. Assange since the WikiLeaks dump (which the Times disseminated).

Meanwhile, there has been no shortage of assaults on Mr. Greenwald, and I’m troubled by the collective scoffing at legitimate inquiries about the timing of the car accident that killed Michael Hastings, a journalist who made a practice of pissing off men in the shadows.

The mainstream media’s apparent lack of concern about modern press freedom illuminates the rift between human intel-style journalists and the hacktivists and mavericks who are taking on the surveillance state.

The leaders of our profession have said little about Mr. Brown, save for the notable exception of some insightful essays by Peter Ludlow, a Northwestern University philosophy professor who writes regularly about corporate security contractors tasked with creating alternate realities to fool the public and undermine activists and journalists alike.

Up until recently, I, too, said, yeah, I’m sure they track me, but I haven’t done anything wrong, and so what if they know about my hypochondriacal midnight Internet searches, if it helps keep Al Qaeda from blowing up Indian Point.

Then something about that AP records sweep turned me. At a dinner recently, when a friend piped up about surveillance as the small price to pay to keep another Boston at bay, I found myself firmly on the other side. I thought of philosopher Martin Niemöller’s famous quote: “First they came for the socialists…”

When they came for the AP, that’s when they came for me—and for every card-carrying member of the mainstream media as well. Deadline looms, brothers and sisters. Let’s not wait until there’s no one left to write.