Last November, a systems engineer at a large company was evaluating security software products when he discovered something suspicious.

One of the vendors had provided a set of malware samples to test—48 files in an archive stored in the vendor's Box cloud storage account. The vendor providing those samples was Cylance, the information security company behind Protect, a "next generation" endpoint protection system built on machine learning. In testing, Protect identified all 48 of the samples as malicious, while competing products flagged most but not all of them. Curious, the engineer took a closer look at the files in question—and found that seven weren't malware at all.

That led the engineer to believe Cylance was using the test to close the sale by providing files that other products wouldn't detect—that is, bogus malware only Protect would catch.

Protect has been highly ranked by a number of industry analysts for its innovative approach to "advanced endpoint security," the broad term used to describe products designed to stop modern malware and other threats to personal computers. Protect bases its detection and blocking of malware on machine learning technology. Rather than use heuristics that look for behaviors matching specific rules, Protect has been “trained” using "the DNA markers of 1 billion known bad and 1 billion known good files," said Cylance's vice president of product testing and industry relations, Chad Skipper. The company's idea has drawn investors; in fact, the stakes in Cylance taken by venture capital firms thus far value the company at $1 billion.

One reason Cylance and other new malware protection contenders have drawn so much investment—over $1.8 billion in venture capital since 2014—is that the malware protection industry is ripe for disruption.

"I've always been of the opinion that the antivirus industry is a little weird compared to the rest of infosec," said Carl Gottlieb, CTO of the UK-based security consulting firm Cognition. "It's the one industry where if you talk to any end user, they pretty much hate the product they buy every year."

But over the past year, competitors and testing companies have accused Cylance of using product tests that favor the company. These critics have also accused Cylance of using legal threats to block independent, competitive testing.

"Even if [Cylance products] score well in our tests," said Peter Stelzhammer, co-founder of the testing organization AV-Comparatives, "they 'trust' only their own sponsored test, where they can dictate the methodology."

Cylance executives, in turn, have accused some testing companies of running tests that inaccurately represent performance—or of outright "fraud," as one Cylance exec has repeatedly asserted in blog posts and interviews.

In an interview with Ars, Cylance's Skipper said that current malware testing was out of step with the real threats. "There are testing organizations that do see the need to change and are working to adapt their testing methodologies," he said. "But there are others who are frankly pay-to-play and will do anything the vendor wants them to do when it comes to the testing. We've seen our software pirated, put in with an older version on purpose, a lack of updates, and those sorts of things."

So Cylance has run a series of its own shootout events to prove the superiority of Protect—tests that at least one competitor has called out as being "unfair."

Such concerns around anti-malware testing extend far beyond Cylance and have existed for years.

"Sometimes you see weird things," remarked Luis Corrons, the chief technology officer of Panda Security, speaking broadly about the industry. "There are many ways to poison a test or try to influence it."

Corrons and Righard Zwienenberg of ESET presented a paper at the Virus Bulletin Conference in October 2016 on the potential gaming anti-malware product tests. In it, they noted a few obvious examples. "Some testers organize their malware testbeds by naming the files by their hashes," the two wrote. "There have been cases where products were not able to detect malware in a file with a ‘normal’ filename, while it was detected when the name of the file matched the file’s hash."

In short, this is an industry where it can be hard to know the "objective truth"—or if such a thing even exists.

Packing it in

The case against Cylance turns on the practice of "re-packing" existing malware samples—essentially turning them into "fresh" malware. Rather than passing prospective customers raw malware samples to test, Cylance first alters the files using software utilities commonly referred to as "packers." Packers convert executable files into self-extracting archives or otherwise obscure their executable code.

Packers have been used by some software developers (and malware authors) for over a decade to reduce the files needed for an application down to one, to control software licensing, or to defeat reverse-engineering or signature-based detection by changing the checksum value ("hash") of the file in question—which may allow malware to slip past signature-based file checks.

Cylance executives said that they have used packing utilities to create "mutated" malware for testing, including some of the samples used in the company's "Unbelievable" demos. "We do exactly what the enemy does," said Skipper. "They share malware and repackage that malware to evade signature-based detection."

Skipper contrasted this with how other vendors test products, claiming that the repositories of malware samples competitors rely on—such as the Anti-Malware Testing Standards Organization (AMTSO) and its Real Time Threat List (RTTL)—are fundamentally compromised.

"If you just go and you pull down malware from any of the well known virus repository sites," Skipper said, "anyone who has a relationship with those sites is going to score a 100 on the test" as a byproduct of already having access to all the malware samples. "So that's not really an effective test, and it's also not representative of the malware that's going to hit or target a human organization. When it hits, no one is ever going to have seen it before. So that's more representative of what's happening today."

The AMTSO says RTTL samples are contributed by both vendors and independent researchers. It's true that some testers use the RTTL, which gets its samples from both malware protection vendors and security researchers, and also tracks the regional prevalence of samples. But some of the leading test organizations don't use RTTL; both NSS Labs CEO Vikram Phatak and MRG-Effitas CEO Chris Pickard told Ars that they collect their own samples live from the Internet and don't share them with vendors until after tests are completed. And there's no shortage of fresh malware out there for others to capture.

In addition to distributing its own malware samples through its “Test it Yourself” website, Cylance has pointed customers to a website called TestMyAV—a source for malware samples and testing methodologies for small and medium businesses to use to evaluate endpoint security products. TestMyAV, which got a shout-out from Cylance Chief Research Officer Jon Miller in a January "Ask Me Anything" session, is operated by Carl Gottlieb of Cognition—that Cylance reseller we mentioned earlier.

Gottlieb said TestMyAv has no connection to Cylance or to his reseller business. "The two don't mix...we just let TMA whir away in the background servicing those that access it," he said. However, TestMyAV also uses packing tools to repackage malware samples.

Skipper's explanation behind malware repacking—that existing collections just aren't fresh enough to be accurate—doesn't get much support from some others in the industry. "Sure, you can create malware," said Luis Corron of Panda Security. "But what for? Why? There are like 300,000 new malware samples every day. If there was some sort of shortage—'malware is so hard to find, no one is getting infected'—okay, fine, but these days the difficult thing is not getting infected with new malware."

There are some obvious problems with using repacked malware for testing. Because of the prevalence of packers in the malware world, signature detection is generally not used as a primary line of defense by endpoint protection products. In fact, some products (including F-Secure) heuristically flag packed files by default because packers like MPRESS and VMprotect have been so closely associated with malware.

Gottlieb acknowledged that, saying that he doesn't use MPRESS (an open-source packing utility), because "Symantec is very good at catching it."

It turns out Protect is also really, really good at flagging files processed with some packers. "The reality is that yes, [Cylance is] very good at detecting packers," acknowledged Gottlieb. But, he added, that's not a bad thing, especially if packed files have been heavily modified—or even if they're benign. "If something has been modified to look like a virus, I'd probably want to know," he said. "I guess it depends on how you look at the world."

Which brings us back to the samples Cylance provided to that prospective customer in November. The files that only Cylance caught in the test were all repacked in some way; five of the files were processed with MPRESS and the remainder were packed with other tools, including what appears to be a custom packer.

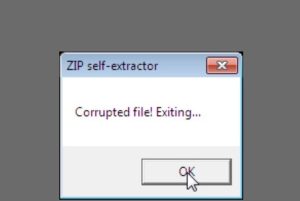

Of the nine files in question, testing by the customer, by Ars, and by other independent researchers showed that only two actually contained malware. One of the MPRESS-packed samples appeared to contain a copy of the MPRESS packer itself. The remainder of the MPRESS files contained either "husks"—essentially empty files—or samples that had been corrupted in packing. Two others crashed on execution, after opening a bunch of Windows resources without using them.

When asked about these files, Skipper said, "We don't give empty files on purpose—it's just not what we do." Cylance contends the non-malware files were included because of an error by a company engineer. (The customer conducting the test in question was unconvinced.)

As for why empty packed files would be caught, Cylance's Vice President of Product Marketing Bryan Gale explained that Protect's machine learning algorithms might identify packed executables as malicious based on what it "learned" about malicious behavior from the training files.

Gale said Cylance Protect will "convict" things as malicious based on their behavior—such as loading junk or empty files into memory—because that might "actually [be] causing harm or introducing a vulnerability on the system." But, Gale insisted, "We're typically not going to go in and blindly block something if it's packed with MPRESS or another packer."

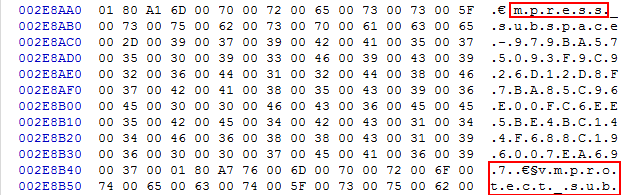

In a December blog post, however, the chief technology officer of MRG-Effitas, Zoltan Balazs, said that he found specific references to the packing tools MPRESS and VMprotect inside a malware protection product while he was viewing its executable code in a hex editor.

"We have no idea what this code does, but it is an interesting coincidence to find these strings in the code of the product, " Balazs wrote."There can be multiple reasons why all packed files are detected as malicious. Either because all packed files are malicious, or because the vendor believes in high false positive ratio in order to have higher true positive detection. Which is fine. But during the demos... every VMProtect packed file will be detected by [Cylance]."

For its part, Cylance denied the screenshot actually showed Protect's code. "It’s a hex view of a sample packed with MPRESS and VMprotect, it looks like," a Cylance spokesperson said in response to that allegation. "It’s a sample from TestMyAV, I believe. It's malware, not Cylance."

However, Balazs insists the code is from Cylance's product. "Yes, it was Cylance Protect," he told Ars, "but we did not reverse engineer their software, we just looked at strings in the binaries." [Update: Balazs further backed up his claims in a YouTube video he posted after this article was published.]

An analysis by Ars of other MPRESS- and VMprotect-packed files found no internal references to either piece of software. (Additionally, Gottlieb had already mentioned he doesn't use MPRESS for files on TestMyAV.)

reader comments

104