You can also listen on Apple podcasts/iTunes, Spotify, TuneIn, Stitcher and Google Podcasts. Search for ‘That Feels Like Home’ to subscribe, follow, favourite, and share!

MoDA objects relevant to this episode

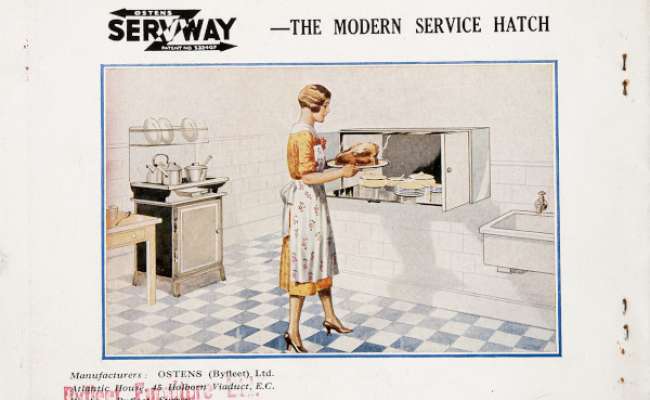

Ostens Servway: The Modern Service Hatch

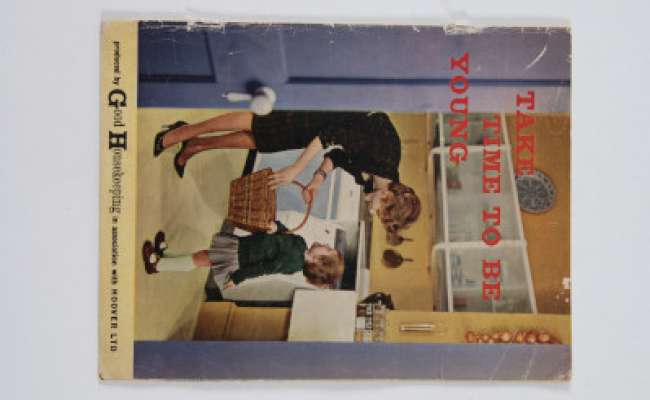

Take Time To Be Young

The One Maid Book of Cookery

Transcript

…No there is no escape from housework! We are three people in our household, and my husband is also working from home, and I’m also working from home, and my kid is also taking his education from home. So we are making three meals a day, we are wearing and taking out our clothes and there are packages coming to our door they have to be taken to balcony, cleaned and then disinfected and then put into new packages again.

So the house feeling became to me much more housework. And even standing at the corner in my house I feel the pressure of this house work. I have to make the breakfast, prepare the lunch, prepare the dinner and wash the dishes. Thanks to my husband that he is, at least helping me washing the dishes, and getting the packages from outside.

If I’m perfectly honest, I don’t think the division of labour has changed that much because he is the person that’s gone to do the shopping. Only one person being allowed in the supermarket, so he’s gone and done that, so that’s great. He does all of our cooking, which is amazing. Again, he’s better at it. He makes nicer food than me, so you know, I do much of the washing up, and I do all of our laundry, but certainly there’s more cleaning that needs doing because there are four people in our house all of the time.

Ana: Welcome to That Feels Like Home, a podcast by the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture (MoDA), reaching you from Middlesex University in London. I’m Ana Baeza, and I’ll be hosting this second season to explore the multiple stories around home in the current Covid crisis. This time, we’re recording in less favourable conditions, from our homes, so please bear with us if the sound isn’t always of studio quality. And in this season I’ll be talking with historians, anthropologists, activists and practitioners to reflect on the many changes brought about by this pandemic on our homes. As usual we draw inspiration from the museum’s collections to reflect on the present through the lens of the past.

Ana: The relationship between work and home has been profoundly affected by COVID-19. As workspaces bleed into home spaces and put pressure on their traditional separation the activities of domestic work have also been impacted. In this episode we consider the histories of domestic work and domestic workers since the late 19th century. Then as now maintaining the home has required skill and constant labour but who’s been responsible for it? We discussed changes in domestic work especially around the so-called servant problem as it emerged in the early 20th century through to the wages for housework in the 1970s, domestic work and migration and new challenges and opportunities we face now under COVID. We’re joined by two guests Rosie Cox and Lucy Delap. Welcome Rosie and Lucy it’s a real pleasure to have you here today.

Rosie Cox: Thank you.

Lucy Delap: Hello.

Ana: Lucy Delap is a reader in modern British and gender history at the University of Cambridge, deputy chair of the Cambridge history faculty and fellow of Murray Edwards College. She has published widely on the history of feminism, gender, labour and religion including the prize winning The Feminist Avant-Garde: Transatlantic Encounters of the Early Twentieth Century and Knowing their Place: Domestic Service in 20th Century Britain in 2011. Her next book Feminisms: A Global History will be published by Penguin in September 2020.

And Rosie Cox is professor of geography at Birkbeck University of London. Her research interests focus on the home, particularly housework, DIY, and practices of homemaking, as well as paid domestic labour and care work in private homes and gendered migration. She was a founding member of the Birkbeck gender and sexuality group and has published widely, including the books: As an Equal: Au-pairing in the 21st Century, from 2018 and The Servant Problem: Paid Domestic Work in a Global Economy 2006.

So thank you both very much for being here. And I’d like to start asking you about housework, in which I’m including domestic work, childcare, elder care, home-schooling, all of this is essential work, it’s what keeps everything going but is often invisible and largely it’s still undertaken by women. And as COVID has hit there’s some research that suggests that women have again been taking more of this increased burden. For example, a recent report from the Institute of Fiscal Studies carried out with 3,500 opposite gender families indicated that women, when they’re still working, are more likely to reduce their working hours than their counterparts to do this kind of domestic work. And 50% of their worktime was being interrupted by shared childcare. So I wanted to start by asking you what you make of these recent analyses and also how this fits with some of the lines of your research.

Rosie: Sure I thought this research was extremely useful because basically it seemed to confirm what a lot of us had suspected which was that in all sorts of ways COVID was just reinforcing lots of trends that already existed. And it seems that women’s totally taken for granted responsibility for care has been writ large at this time, and that when you have a family where there is a mother and a father and both parents have started working from home the additional burden of home schooling and childcare it’s just taken for granted that the woman will try and do that alongside her job. And we also see that one of the reasons why women are more likely to cut their working hours is because women are paid less. So it’s a logical thing for a family to do to say that the woman will cut her working hours. And so we then have this real structural reinforcement of women having a lesser place in the workforce, that families act on and seemingly in an individual and logical way, but actually it’s a social process. And that’s just been, like I say, writ large by COVID.

Ana: And I wonder how that fits with some of the historical trajectories of this phenomenon and whether Lucy you might be able to comment on that from your perspective of the histories that you’ve looked at of labour and work in the home?

Lucy: It is really interesting when we look at this historically because this idea that there might be a shift whereby domestic labour becomes more equally shared is encountered across the 20th century at numerous moments, people keep finding what they might call companionate marriage, a more kind of reciprocal, more equal kind of marital relationship or sometimes it was termed the symmetrical family, the idea that men and women might make equal contributions within the home. That is repeatedly discovered in the interwar years, in the years after World War II in the 1980s and 1990s. And the fact that it has to keep being discovered reminds us really of the limits of it, that although it’s talked about there’s a rhetoric of equality and sharing, when you actually do the counting up of the hours of labour it doesn’t ever measure up to the idea of equality.

So I do think there are changes across the 20th century in who does work and in what kind of work is undertaken within the home. And there is a shift actually in the last sort of 30 – 40 years whereby certain kinds of labour are more likely to be shared, in particular some of the parenting work – it’s less about mothering it’s more about parenting, fathers are more present in the lives of their children. But what isn’t shared, and what remains a real source of inequality, are the less favoured kind of domestic tasks, the boring stuff of the washing up and the nappy-changing and so on. And also of course the organisational labour, or the ‘worry work’ as some people have termed it that mothers and female caregivers tend to take on around making all the arrangements happen. So it absolutely doesn’t surprise me that this report from the Institute of Fiscal Studies reminds us that women are doing that disproportionate form of labour.

Ana: And when you talk about the arrangement of tasks I wonder are you thinking also here about I suppose the emotional labour, the mental load of even delegating those tasks in the home? Is that what you’re getting at or could you expand on that point?

Lucy: Exactly yeah the idea that someone needs to have the plan in their head, somebody needs to remember the dentist appointments. Even if they don’t end up going to the dentist somebody needs to have that sort of controlling role. It would be nice to think that those things could be shared more equally but in practice they do tend to be taken on by women, and I include in that absolutely the emotional labour of remembering to buy the present for the birthday party or remembering to send a card at Christmas or whatever it might be. That kind of work is what it is to create kin and to create family. Danny Miller the anthropologist talks about ‘making love in supermarkets’ and he gets that idea that when women go and do the family shop they’re not just putting the meal on the table they’re actually attentively caring and choosing out snacks and treats and preferred foods, and avoiding foods that some people in the family don’t want to eat. And I love that idea of the making love in supermarkets; it’s the capturing of emotional work and organisational work which is absolutely not shared in current households.

Ana: Right so there’s this interesting aspect I guess of all the affective dimensions that accompany the care work, housework, but I wonder what you make of this in the context of what other have been saying that actually there is a silver lining in this recent report that does suggest that men are picking up some of the housework during this COVID pandemic and whether this could potentially shift gender roles but whether it might do so bearing in mind all of that emotional affective labour that we were just talking about, if you have some thoughts on that?

Lucy: So there’s still a massive disparity in terms of hours worked but you’re right that there have been some indications that men are doing more. I still think that the kinds of tasks that they’re likely to pick up are quite gendered, quite stereotyped. The silver lining for me has actually been the prospect of involving older children more in domestic labour and I think anecdotally lots of people have said to me, ‘Oh yes it’s a great chance to get my kids to cook, or get them cleaning the bathroom or sweeping the stairs,’ or whatever it might be. So I like the idea that we could throw this a bit wider than simply thinking about the gendered division of labour and think about what children might do in the home as well, and of course to remember that some children are primary caregivers and those young carers already know absolutely what it’s like to clean the bathroom and sweep the stairs.

Rosie: I completely agree with what Lucy’s saying that yes there has been some evidence of men doing a little bit more domestic work during lockdown but proportionately nothing like the growth that women have seen in the burden of work that they’ve taken on. We’ve also seen that what men have tended to take on is parenting, as Lucy was saying before, rather than the additional cleaning. And some families have taken on masses of more additional cleaning as well as things like supermarket shopping being much more time-consuming, you know if you have to stand in line and this kind of thing.

So the research does show that men have tended to do more of that, the socially valued parenting work rather than the toilet cleaning end of domestic work. And there’s certainly been no evidence of that worry work shifting between family members. I think for me the silver lining is about the fact that we’re having these kinds of conversations that lots of families, including lots of men who perhaps were not aware quite how much labour went into running a household have suddenly had it forced under their attention. And I think that there has been the time-consuming nature of all forms of care work, the importance of this work has been hugely important during the COVID lockdown and for me that’s part of the silver lining is the visibility of all these different forms of care work and domestic work that we’re actually having these conversations about why they matter and who’s doing them.

Ana: We’ve been talking about the way in which work is distributed in the household but the nature of households has obviously changed a lot so I wonder if you’ve got some thoughts, both from the historical perspective but also thinking about what household are like now? Lucy would you like to start?

Lucy: Yeah thanks Ana. Well I mean historically across the 20th century we’re seeing quite a lot of demographic change and a reduction in the number of children which I think changes the nature of the household and the kind of labour within it. And of course that goes with technological changes that massively change the nature of the household. And just thinking about the contemporary situation we talked about redistribution within the home and who is in that household is changing. When we look at the kind of profile of UK households there are, you know more than eight million people who live alone, there are a lot of single person households, as we’ve seen with the debate about loneliness during the COVID lockdown. There are a lot of young people in their 20s or early 30s who live with their parents, about a quarter of young people of that age group live at home. There are a lot of same sex families, a vastly growing category in the UK. So in terms of sexuality and generations and demographic patterns this question of who does the labour and how do we redistribute is not as simple as simply saying, oh well there’s a man and a woman as a couple and we need to think about the distribution of labour between them, actually the household is a much more complex and historically changeable category.

Rosie: I think it’s very, very easy when we talk about domestic work to kind of revert it to the stereotype of thinking about the heterosexual nuclear family, because housework is so much part of the gender wars between men and women and when we have children present it’s much more of an issue generally than when we don’t. But we do need to be sensitive to the changing nature of the household and the way that it creates different demands for domestic work, for different forms of care work, particularly as the population ages. And it is a much more complex and nuanced environment than a lot of the simplistic descriptions of women do this and men do that, might perhaps suggest.

Wages for housework [14.15]

Ana: I’d like us to think a bit about the precedents of these discussions because feminists have been speaking loudly about this, about the importance of housework to sustain everything else for a while now, especially if we think of the 1970s Wages for Housework campaign, as a transnational campaign travelling through the US, Italy, Iceland, involving people like Silvia Federici, Mariarosa dalla Costa. So I’d like us to explore that a little bit, also I think Lucy you’re probably addressing this in your upcoming book. They pointed out that the traditional separation between breadwinning and housework was fictitious because housework actually is what helps capitalism reproduce itself. So as part of that campaign Wages for Housework, they were calling for housework to be waged, which is not something we’ve touched on so far. So I wonder can we explore a bit this movement, what were the ideas that they were fighting for and that question of having paid domestic work?

Lucy: The Wages for Housework campaign is a really fascinating episode in feminist history and it was based on the intellectual inspiration of Marxism, of the recognition that so-called reproductive and productive labour are linked and that you can’t have any kind of production without reproduction, and by reproduction of course that’s not just the biological creation of labour through sex but also the domestic labour that is required for the upkeep of human life. So that was a very rich strand of thinking that enabled Marxist feminists to link up the domestic and paid labour. And it’s no surprise that it came about in the 1970s which was a period of enormous change, of austerity, of inflation, of real disruption to the status quo in a sort of geopolitical sense in the headwinds that the global economy was facing, but also a time I think when domestic labour was intensifying, where there were expectations around particularly children and the kind of intensity of parenting, but also around the kind of changing nature of the home and what kind of technologies were found in it. And that created this real momentum for rethinking domestic labour and its value.

And I would say actually that I think it’s very similar today, I think we’re also in a historic moment where things are changing, where there’s a lot of intensification of different kinds of labour regimes and again opportunities to rethink the status quo. And when you unpick what sort of things they were talking about: I think calling it Wages for Housework actually slightly short sells the ambition and the kind of conceptual breadth of what they were doing because the proponents, Selma James, Mario Rosa dalla Costa and so on, they weren’t simply saying, oh let’s take domestic labour and make sure it gets paid. In fact they had a broader critique that was talking about the need to work less, the need for labour to be a less alienating, dominant form of human experience. And that really resonates with me today where we’re actually seeing around the world people talking about, well what might a regular four-day working week look like, what would it be like to simply work less? And of course lots of people on furlough or made unemployed in COVID have been confronting work featuring less in their society, sometimes causing great distress. For other people it’s been a creative moment where they’re rethinking what shape their life might make. And that same campaign in the 1970 also produced talk and thinking about what a guaranteed income would look like.

So Wages for Housework doesn’t look that dissimilar to people today talking about a universal basic income. And in a way they narrowed and strategically chose that kind of specific question of the need to pay people for domestic labour, women primarily, but actually their goals were broader, they were really trying to shake up the whole economic system and the way in which it intersected with systems of the sexual division of labour. So that is super exciting. It’s also worth saying perhaps that they were criticised strongly at the time and subsequently for proposing a policy solution that seemed to root women more in the home, that seemed to say, yes you do a lot of housework, we’re not going to change that we’re just going to revalue it, we’re just going to give you some resources to say thanks you’ve done this labour. And for a whole generation of feminists, people like Shulamith Firestone they were saying no we don’t want women to be rooted in the home, we want women to have choice in their lives for any kind of options and for lots of women that doesn’t involve domestic labour or care work. And so there was a real tension there between this fear that Wages for Housework was really just rewarding women for something that was actually a very confining role. And the Marxist interpretation which is, this is labour and it should be paid for, it should be given it’s true worth. So it was never like a straightforward campaign but I think it did speak to the interests of a lot of working class women who felt that feminism as it had previously been constructed was all about professional women, educated women, women who wanted to free their sexuality and experiment with new forms of living, they felt that the housewife role had been kind of devalued so they wanted a form of feminism that spoke to them, that said, yes we respect your role as a housewife, we don’t denigrate being a housewife, instead we want to give you social and economic approbation for the work you’ve done.

Ana: On this point about the criticism to Wages for Housework as rooting women in the home, doesn’t that raise the question of then who does the work, ultimately this is labour that someone needs to do, so could it be organised and redistributed differently?

Lucy: I think a lot of feminist projects have confronted that difficult question of, you know so who does this then? And quite a lot of projects that have called for a revaluation or a rethinking of who does that work have ended up saying really this work needs to be socialised, this work needs to be done as a public service, it needs to be devolved out of the home and devolved onto other kinds of workers. And so there’s been all sorts of schemes and we might talk about some of this later, to take domestic workers and to support their work better, to nationalise domestic work if you like. But it is tricky because I think personally it has to be done with also a recognition of the need that some work that stays in the household might be redistributed. So I think there’s a kind of twin track here around who we imagine and the work being done by and how it might be done.

Domestic workers

Ana: That leads to something I wanted to ask you about as well which is moving on to thinking about domestic workers when that is privatised or it’s not performed within the context of the family, when families can afford to then bring external domestic workers to do that work that would have previously occurred within the household. And both of you have done work on this area, you Lucy more in the early to mid-20th century, and Rosie you’ve looked at a later period from the 80s to the present. So building on what Lucy was just saying could you expand on this question of domestic work?

Lucy: So there was a huge growth in domestic workers, mostly female, vastly disproportionately female, in 19th century Britain and that paralleled other countries round the world such as the US, Australia. Domestic work became one of the largest sectors alongside agriculture for women’s work. And that peaks, in terms of its size within the economy, the very late 19th century, the 1890s and in terms of absolute numbers working in domestic work it’s continuing to rise until around the 1910s. It then tails off to some extent across the 20th century as you have different options emerge for women workers, but my historical research suggests that while it tails off in the formal sector you have a growth in the informal sector that to some extent takes its place. So instead of having a formally employed live-in domestic servant, if you’re a middle class or upper middle class household, you might instead have a cleaner, a char, a mother’s help, you know there’s a whole variety of different words that are used there.

And maybe that kind of variety of terminology is a sign of how slippery that role becomes, that it becomes hard to see it in the archive, it becomes hard to capture it in kind of formal records. And people who can afford it continue to have this fantasy or this reality that they can get other people to do that work, and it’s very much dependent on the nature of the economy and when you see economic downturns you see more women taking on those roles because they don’t have any other economic options. And I think the same is likely to be true after the economic fallout of COVID hits us and the same was true in the 1980s with the sharp downturns that you saw then and also similarly after the 2008 financial crisis.

So there’s always been a place in the economy, whether it’s formal or informal for domestic workers and I think for a lot of 20th century married couples maybe they did have ideas about symmetrical family, about shared domestic labour but when push comes to shove there’s a lot of conflict over how we distribute domestic labour. And some wealthy families have been able to avoid conflict by devolving so that households are able to not have to face up to the tricky question of who cleans the loo by paying for a cleaner or an au pair or a char to take on that work.

Rosie: Picking up the story from where Lucy’s research leaves off, you know in the mid to late 20th century, what we saw, as Lucy said, from the financial downturn of the 1980s was an increase in the number of domestic workers that we were tracing in the UK and the same trend was found in the US. In other parts of Europe it tends to be a rise in the number of care workers, in Italy for care workers for elderly people working in their homes, but we see this kind of slow growth in the late 1980s, 1990s, and continuing today.

And across the world what we’ve seen historically is that the number of domestic workers correlates with economic recession, so when people don’t have access to other forms of work or women don’t have access to other forms of work that they’ll move into domestic work. But also that the number of domestic workers correlates with inequality in society. So as the incomes of the richest move further away from the incomes of the poorest and the expected earnings for people at the bottom of the wages pyramid then we see a growth in the number of domestic workers.

And as you’re probably very well aware the 21st century has seen extreme polarisation of wealth in a lot of countries, the UK amongst them, and with that we’ve seen a growth in very many different forms of domestic work. As Lucy says in most families that would probably take the form of a cleaner who comes in for a few hours a week and has that incredibly important role in the family of stopping the arguments, possibly stopping a divorce from happening down the line, so it’s very valuable work indeed for a lot of households. We also have seen an increase in people who are involved in providing childcare. Until around 2007/8 that would have been nannies as well as au pairs. Since the change in regulation in 2008 that’s almost entirely au pairs with nannies only being employed by very wealthy families. A nanny could cost you £50,000 a year if you’re employing them properly under all the legal rules. Nannies are meant to be inspected by Ofsted as well as paid on the book, so tax, national insurance and things, whereas an au pair is only given pocket money of maybe £80 a week, so they kind of fall into different positions.

We’ve also seen a massive growth in care workers looking after elderly people as the population ages and the State hasn’t backfilled, hasn’t really expanded enough to do that. And then at the kind of top end of the spectrum we also see an increase in not only things like butlers, you know those domestic workers who are there for status but there are also the chauffeurs, the pilots of private jets and helicopters, the private hairdressers and beauticians and things like that. So at the pinnacle of the ultra-rich people have these whole teams of quite specialist workers who keep their family rolling, looking as they’re meant to, their children not only privately educated but tutored by teams of specialists, they have private chefs all that kind of thing. And then at the other end of the hierarchy we have the cleaners working just a few days a week. And all those parts of domestic labour have grown with extreme inequality in the 21st century.

Ana: The last description that you were giving Rosie was making me think of that recent film, that South Korean film Parasite…which you probably both saw and you were talking about the question of the polarisation of society and how increasing levels of inequality have the impact of increasing these kinds of care work and housework, and obviously we know that a lot of it happens as an informal economy as you’ve said and how much of that precarity [sic] and lack of security will have been exacerbated by COVID and by the conditions of the pandemic. So I wondered if maybe Rosie you could start and you could comment on this and especially in terms of going forward how you think in the aftermath of COVID what we might be seeing and Lucy of course if you’d like to comment on that as well?

Rosie: Okay well to start with the during COVID it’s actually been very interesting that the situation of domestic workers has again been made visible in a way that it isn’t normally and there are have been reports from a number of different countries about specifically what has been happening to domestic workers. So when we saw the beginning of the lockdown in India for example of lots and lots of rural migrants were trying to return to their home villages, lots of those people were domestic workers who were like suddenly expelled from the urban households that they were working in.

We’ve seen the plight of domestic workers in Brazil has been really important and quite relatively well reported for the extent to which domestic workers are often ignored. The first person in Rio to die from COVID was a domestic worker and she contracted the disease because her wealthy employer had been on a skiing holiday in Italy and brought the disease back. And in fact that’s what’s happened across Brazil is that it was largely relatively wealthy people who started with COVID and then passed it on to their domestic workers who then were living in overcrowded conditions in poorer neighbourhoods and it spread into poorer neighbourhoods.

And domestic workers have found themselves vulnerable to COVID in two ways, either they’ve been told not to work, please go away, and therefore they haven’t necessarily had any income and because very few domestic workers are formally employed they haven’t been able to be furloughed. So that’s one way in which they’ve been vulnerable is they’ve just been made unemployed. And sometimes that’s been domestic workers who were living in who’ve just been kicked out. So I know of au pairs who just got kicked out of the families they were living in, go away, get out of the house now, regardless of the fact that the countries that they came from were not allowing people to return.

So those people were made extremely vulnerable put at very high risk because they were not seen as being members of the family and were seen as not appropriate to be there during the disease. Other domestic workers have been put at risk by not being allowed to return home and being asked to keep working and to keep moving between their own household and the people that they work for and not having control over their exposure to the disease that way. So COVID has been really important to the vulnerability of domestic workers and they’ve been in a very unusual situation because of their place inside and outside the household. During COVID the household has become the unit of disease control, that is what lockdown has created and domestic workers have been one of the few groups that has this very strange status as both inside and outside the households who they work for.

Post-COVID what is likely to happen? We know that the recession is going to hit people who were in personal service and hospitality work. Women have been hit particularly hard by increasing unemployment whereas people with office jobs that they’ve been able to do from home, or middle class people have largely kept their work. So that polarisation of incomes has also increased during COVID. And these are all the conditions that we would expect to underpin a further increase in the extent of paid domestic work.

Lucy: Rosie’s absolutely right to say that this is an informal sector and these workers have been incredibly vulnerable to COVID but maybe it’s worth, on a more optimistic note, saying I do think there has been a revaluation of domestic labour, of cleaning, of the care of children and so on during this lockdown. It’s been extraordinary to see the way in which cleaning services which were always the Cinderella of public sector employers, like hospitals and schools and so on, suddenly realising actually these could be our most important workers. If anyone is going to be brought back it’s going to be the cleaners. And I don’t know whether that will have a knock on effect around the value of activities like cleaning within the home but I’d like to think that it’s possible for us to see cleaning and the reproduction of human life in its full spectrum of activities as changing, as being recognised to be super, super important and valuable after the lockdown.

Ana: You’re listening to That Feels Like Home. I’m Ana Baeza and in this episode I’m talking to Lucy Delap and Rosie Cox about domestic work during Covid and the histories of housework. Stay tuned to hear us talk about domestic workers’ campaigning, rights and the intersections with feminism.

Agency

Ana: Lucy, in your work you talk about ‘agency’ to refer to the ongoing debate among historians as to the extent to which domestic workers might be able to act as historical subjects, which is important to think in relation to campaigning and organising for workers’ rights, then as well as now. Could you explain more how you’ve approached this question?

Lucy: You’re absolutely right: is the clap for the keyworkers outside of one’s house just an empty round of applause or can it be translated into better conditions, better pay, more social recognition of the value of this labour? So we talked about agency and it’s been a hugely important part of history from below, subaltern histories, social histories, the kind of histories that are about the people whose labour is informal, is precarious, is not valued. It’s been important in those histories to say, actually people do act. These workers, these caregivers they do have the power to change their lives, to act in significant ways. So agency is a way of capturing that.

Now I’ve written about this recently to say yes it’s great to show agency but that we shouldn’t be satisfied with that as a full account and what we need to do is say, well what kinds of agency are expressed because it’s I think banally true that all human actors, historical actors have the power to act in one way or another. There is a great literature on this in relation to domestic service, and I’m thinking here of the anthropologist James C Scott who wrote a book called Weapons of the Weak, a very, very significant book that has launched a thousand ships of other studies. And he was interested in what people who don’t have formal power can do to construct their worlds and change their situations.

And in specific terms in the historical literature on domestic workers this is all about the noises off, if you like, the slamming doors, the go slows, the spitting in the soup, the ways in which domestic workers would sometimes very clearly make their voices heard or make their views heard. I would say though that there’s also a lot of evidence in the historical literature that there were limits on that. You can spit in the soup all you like but is it going to get you a pay rise? You can threaten to resign all you like and at some point you’re actually just going to lose your job. So agency is this contested category and when we look at the efforts to organise domestic workers they have been stymied by the fragmentation of that sector, the fact that a lot of domestic workers are very isolated. Sometimes they’re of migrant origins and they are not very well connected necessarily into their host society, they may not have the good language, they may not have networks of support. The union movement which has been hugely important in supporting low paid workers to come together hasn’t got a very good record historically on domestic workers.

But I would say that it’s very exciting that we’re seeing some very powerful shifts towards organising precarious workers, whether that’s the McDonald’s workers, whether it’s hospital cleaners, whether it’s people working in fruit picking. The union movement has recognised I think that it can’t afford to stick with the sort of formally employed, traditional sort of working class roles in manufacturing industries say, and that it needs to go into those service sector roles and into the informal economy and do something about those workers to compel change. So I’m broadly optimistic that there are ways forward even though when I look back it looks as though domestic workers did really struggle to be agents in terms of trade union approaches to organising. So a lot of their agency and the change that they made happen was at these very micro levels of resisting employers on a kind of every day basis.

Ana: So Lucy you’ve mentioned the fractured nature of domestic work so I wonder Rosie if you could expand on that a bit, given that you’ve done research in those areas?

Rosie: Yeah sure, I’ll definitely do that and also tell another good new story about some of the progress that domestic workers have made. So one of the things that Lucy’s made reference to is that domestic work is fragmented, that domestic workers might have an awful lot in common but one of the things they rarely have in common is their workplace or their employer. So unlike other workers who’ve been unionised you can’t get a whole group of people together who work for the same employer and ask for collective bargaining. And that’s kind of frustrated traditional attempts.

But domestic workers quite often have organised, maybe alongside unions or outside unions, and they have made some gains and quite often the issues that they will be tackling, as well as being about their working conditions, their pay, will be really intimately tied up with their migrant status because in the global north there are huge numbers of migrant domestic workers, it’s not necessarily the case in the global south, so quite often we have people are migrants but they are from rural to urban areas within the same country. But in Europe and North America and in Australia we have the complication that lots of domestic workers have a visa status or a migration status that gives them less rights than other workers or that they might be undocumented so they have additional worries around that. So quite often campaigns can integrate both the desire to have a stronger position for the visa, like a visa that lasts longer, that kind of thing, as well as being about working conditions.

But quite often that migrant status is double-sided, it means it’s very difficult for people to organise because they don’t want to raise their heads above the parapet but on the other hand we quite often have organisations, so Filipina domestic workers have been really important in a number of countries around the world in organising together as a national group and pushing for domestic workers’ rights that way and they might come together in cultural associations and then carry on to push their cause as domestic workers. So we see these alternative ways of organising.

But the good news story which I think is really worth thinking about is that at an international scale there’s been a huge leap forward in terms of the recognition of domestic work which was done by the International Labour Organisation and the passing of something called Convention 189 and this made the demand on all members of the International Labour Organisation, which is most countries in the world, to introduce the same rights for domestic workers as for other workers. Which when you think about it, it should be a no-brainer, like why shouldn’t domestic workers have exactly the same employment rights as exist in the law of your country? But there wasn’t a single country in the world where they did. And since Convention 189 was passed in 2011 a small number of countries have been slowly signing up to it. It’s still a tiny minority compared to the total number that could, and the UK is not one of them, the UK will not agree to give domestic workers the same rights as other workers.

But there have been a couple of countries that have signed up which are really important. So again Brazil, Brazil’s very important in these debates because it employs the single largest number of domestic workers of any country in the world. And it did sign up to Convention 189 and introduced workers’ rights for domestic workers and that’s actually had a huge effect on the sector there and has changed the organisation of domestic work from being almost exclusively live in, to much more often a live out job, so that domestic workers can go home to their own families at the end of the day and are generally in a much better position because of that. So there are some histories of really successful organising like even at that great international scale. So we shouldn’t think of domestic workers as being entirely beyond having quite large scale agency sometimes.

Ana: Thanks very much, Rosie, I didn’t actually know about that Convention. In terms of domestic workers’ rights, could you expand on that, what rights are we talking about and how does this compare to other workers?

Rosie: Yeah sure. So say for example if we take the example of the UK the rights that people have because they’re workers would be things like there’s a maximum number of hours that you can work per week, it’s 48 hours per week in this country, unless you sign that you’re not prepared to do that. You have a right to having a certain amount of leave. You have a right to health and safety protections. So those are the kinds of rights that you have because you’re a worker.

Domestic workers don’t have those rights in law. So say for example in the UK we actually still have the category of domestic service, of a domestic servant, and it is written in law that a person who has that role is not protected by the European Working Time Directive, there is no limit on the number of hours that somebody who is a domestic worker can be asked to work in Britain.They have no right necessarily to having holiday. And that’s common across the world that whatever rights exist in law for workers there will be an exemption that says this does not cover domestic workers. This particularly affects live in domestic workers rather than somebody like a professional nanny who comes and goes. So before Convention 189 there wasn’t a single country in the world where domestic workers had equal rights to all other workers. Generally domestic workers don’t have access to minimum wage in the same way as other workers.

So as I’ve been saying in lots of regimes the law says protections for workers don’t affect somebody who lives in. So in this country for example we have minimum wage but we have an exemption to national minimum wage legislation for people who are called family workers, who are live in domestic workers. So living in also means that there are no health and safety protections, the domestic home isn’t recognised as a workplace for ordinary health and safety protections. So legally living in is bad.

But it’s also where the emotional mess happens that means that domestic workers can be super-exploited. So whilst a domestic worker who’s working say 40 hours a week for their employer and then might have to go home and do second shift at home, they’re unlikely to be working as hard as the way the live in domestic workers who are working in the very worst conditions are. So we see cases of domestic workers who are working seven days a week with maybe four hours sleep a night, month after month after month. We see people not being paid, having their passports withheld, being victims of physical sexual and psychological abuse. And because they never leave the house, because they live in, they can’t report it and they can’t seek help. So the ability to treat a domestic worker really appallingly is underpinned by the fact that they live in. So living in is problematic in all sorts of ways.

Lucy: And just following up on that historically Rosie is absolutely right living in does not have a good profile when we think about Britain and its 20th century servants where it was sort of recommended good practice to have a working day that could start as early as 6am and it could go on as late as 11pm and within that you might have a significant number of hours off in the afternoon. But workers constantly reported that during that so-called time off in the afternoon, let’s say it might be 2 – 6 or something like that they were asked to, oh, you know you’re just sitting around would you mind doing this darning, or while you’re going out for a walk could you just pop to the shop and get this stuff? So they felt that their time was never their own, they were often expected to still answer the door during their afternoon off and that sometimes meant making sure that they were fully wearing uniform to answer the door, the kind of black and white cap and apron that we associate with domestic service. So servants really resented the way that they felt as though they couldn’t have hobbies, that they couldn’t have friendships, that their attempts to court and so that their own families were often very heavily policed or just made impossible and so that nexus of demands created by living in made domestic service a really unpopular profession. Even though servants found that they could often make a decent wage and save money because they didn’t have many other expenses most young women employed as servants in the early 20th century still talked about how much they hated their jobs.

Feminism and domestic work [44.55]

Ana: Lucy I think just on what you’re saying now there’s something I’d like to bring up which might be a small sort of sticking point in the early history of feminism in the turn of the century, early 20th century and it’s the ways in which whilst domestic workers as you were saying would have been doing all this work for endless hours at home this might have been making some women suffrage activists to devote their time to campaign for women’s rights. So I wanted to ask you both about this relationship between feminism and domestic work because this is something that we might still be seeing today as women might be employing cleaners or domestic workers and how do you see this historically but also in more recent times?

Lucy: Well maybe I’ll start on the historical front there and yeah there are very strong links between the ability to employ a servant and one’s ability to devote time to campaigning of all sorts of different kinds not just suffrage but also the enormous amounts of philanthropic work that middle and upper middle class women did in the early 20th century.

I was really fascinated by this when I was reading the suffrage press of that period and found in the correspondence columns lots and lots of letters from domestic workers, domestic servants, and from their employers, from mistresses, discussing the nature of the work that was being asked of servants and their pay and so on. So feminism certainly provided a site at which those things could be discussed. Sometimes with good grace, sometimes with quite a lot of hostility and grumbling, and it is a kind of tension I think within the early 20th century women’s movement that it certainly was a space where women’s labour was recognised, where it was sometimes really valued, where servants and their problems were sometimes taken very seriously. So the Domestic Workers Union for example which was founded in 1909 and which Laura Schwartz has just written a terrific book about, that is a product as much of the labour movement as the suffrage movement, it’s very much a coming together of those two projects and lots of the chief figures in that union were also involved in the Women’s Social and Political Union, the militant suffrage organisation and other suffrage bodies. So we shouldn’t just take a simple analysis here that saying, oh it was all based on the labour of servants that allowed middle class women to go and have their suffrage fun, if you like. I think there’s a bigger story about how there were possibilities of dialogue across class boundaries and where working class women often felt that women’s suffrage was a cause that mattered a great deal to them. We certainly shouldn’t think that suffrage was only a middle class movement; there was a very strong, particularly northern English, industrial town, working class suffrage movement.

However there’s also a lot of evidence in those letters and interactions that we see in the feminist press which suggests that middle class women were not that keen to hear what it was like to work as a domestic worker, where they would look at a letter from a domestic worker describing her working day and describing how she doesn’t get any time off, how the wages work out to be very little. And saying, surely this can’t be true, you must be mistaken, just simply refusing to believe that testimony; and listing out their own sense of, well you know the domestic worker costs me 1s6d for their food and this amount for their uniform and I get this amount of work out of them. So they were sometimes pretty coldly clinical about their economic interests in being able to use that labour, to draw on that labour.

So there’s certainly a sense in which the class conflicts did pervade the women’s movement and I don’t think those things were resolved because I think if you look across the 20th century you continue to see wealthier women, educated women, sometimes treating it as their kind of birthright to be able to employ poorer women to do their domestic labour. And I would say that sometimes that precluded having difficult conversations about the extent to which men should be expected to do that labour. So it’s like a long running stone in the shoe of the women’s movement and of feminist history.

Ana: And possibly still to this day? Rosie if you want to add something to that?

Rosie: Yeah I think so. I was also thinking of my favourite story from history is in Alison Light’s absolutely wonderful book about Mrs Woolf and the Servants about Virginia Woolf and the way that she used to make her housekeeper take the minutes for their Labour Party meetings ((laughs)) so the housekeeper was appropriate in the room but not as a member of their little Labour group, only as the servant.

Yeah I think this is a very interesting question and it was silent in this country in the women’s movement until relatively recently and is just starting to be voiced again now and I think Lucy’s description of the stone in the shoe is precisely correct. In other countries it’s a much more active debate, and again in Latin America there’s a very active discussion of exactly how middle class feminists who rely on domestic workers, and this includes academics who are publishing all the research of paid domestic work, what their relationship is to the domestic workers that they employ. And some of that’s led to progressive employer groupings who introduce a good contract, so minimum working hours and a good rate of pay for a particular area that they’re living in, so that the middle class women have organised as employers to try and raise standards rather than directly supporting domestic workers’ agency of their own.

But I think Lucy also raises this point that domestic workers do not only free up women to do these things, they free up men as well. And whenever we see politicians being caught out because they’ve employed somebody who’s undocumented it’s always seen as being the woman who’s employed that undocumented worker. But, you know men live in houses, men make dirt in toilets, their beds do not miraculously make themselves as they jump out of them, their laundry does not do itself, their food does not cook itself. And you know somebody is doing that labour that is freeing up men and we have to keep making that obvious that it isn’t just women’s labour that’s being replaced.

Care and caring

Ana: Yes absolutely I think this goes back to some of the things we were discussing at the beginning and that distribution of labour which leads me to the subject of care. So we’ve been seeing increasingly that people are working longer hours, two incomes are needed to support a family, there’s a diminished welfare state and some academics, scholars have been speaking about for a while now about this crisis of care. And I guess through the pandemic much of this has been made more visible as we were saying earlier. So how do you see this crisis of care evolving into the future?

Rosie: I think this comes back to a point that Lucy raised right at the start, when talking about wages for housework that this crisis of care shows just how intimately intertwined what happens at home is with what happens in paid work. And I think the question of the crisis of care isn’t just about care, or maybe isn’t even primarily about care it’s about the conditions of paid work. And it’s only when we ask questions of how paid work is organised, how much of it we ought to be doing and you know under what conditions that we can then say there is a capacity to care. So I think if we can ask those questions about why do we work five days a week, why is the number of hours on average that we work growing, for the first time in history, you know it’s been declining for a century or so, why is it going up? Why do we need so many more hours of paid work to ensure a reasonable standard of living? Those are the questions we need to ask in order to solve the crisis of care, as well as attending to the value of care and, you know celebrating it beyond just standing on the doorstep clapping.

Lucy: I think this is really interesting this question of care and I was thinking about this when we were subjected recently to the depiction of the UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, who has just become a father for not the first time ((laughter)). He was trying to demonstrate, you know how great he is I guess and he showed us doing a load of press-ups on the floor of his office. And it’s extraordinary to me that that is quite a macho act and yet, you know he must also be aware that there is a form of care-giving, of care work that he could have depicted, you know he could have talked about what it’s like to have a new baby at home, how that might impact on his work and the work that he might be doing around his growing family. And instead we get an almost Putinesque presentation of him doing these office press-ups. It reminds us of how, yes we’re in a situation where care and domestic labour has been put in the profile, has been revalued, but there are real limits to how far our public conversation takes account of that.

So I guess going forward I would like to see certainly a kind of entrenchment of this question about what do we value and to show how unpaid care work and domestic labour is valuable. I’d like to see a reversal of the tendency for the State to get out of providing that care, the closure of nursery schools in the UK for example. And it would be great to see a renewed public commitment to that care. I’d like to see a redistribution within the home around who does the work, and I’d like to see us really listening to care workers to, you know to amplifying their voices, to hearing about their testimony about their labour and their experiences. And I’m kind of cautiously optimistic that we are actually listening to cleaners and people involved in home schooling and people who are facing the enlarged burden of domestic care at the moment, I think we are hearing their voices and that for me has got to help us create sort of momentum for change.

Rosie: I think Lucy is completely right that we have seen the moment when we are asking questions about how all these different forms of care and carers are being valued and that public conversation is just extremely welcome and I do think that there is some optimism. We know from history that progress in this area is slow and not necessarily always forward, but I do think that this moment has really just made so visible how important caring is and all the myriad forms that it takes. So I hope that we will build on that and not forget this as we have, you know as some kind of bad memory the terrible pandemic that we don’t look back on.

Ana: Well thanks very much Lucy and Rosie for joining us in this discussion.

Lucy: It’s been an absolute pleasure. Thank you very much Ana for hosting us.

Rosie: Yeah absolute pleasure.

Ana: Thank you so much to our guests for this episode, Lucy Delap from the University of Cambridge and Rosie Cox from Birkbeck, University of London, for joining us in this conversation around domestic work and domestic workers. In this episode you also heard the voices of Esra Bici and Kate Murray, who lent their impressions of housework during lockdown, and we’re very grateful for their contributions. I’m Ana Baeza and this podcast is brought to you by the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, Middlesex University. We’ll be back again with more episodes, touching yet more aspects of home life and the everyday under Covid. Stay tuned.

Further Reading

Burikova, Z., 2006. “The Embarrassment of Co-Presence: Au Pairs and their Rooms” Home Cultures 3 (2), 99–122.

Cox, R. and Busch, N., 2018. As an equal? Au pairing in the twenty-first century. Zed Books.

Cox, R., 2018. Gender, work, non-work and the invisible migrant: au pairs in contemporary Britain. Palgrave Communications, 4(1), pp.1-4.

Cox, R., 2013. Gendered spaces of commoditised care. Social & Cultural Geography, 14(5), pp.491-499

Cox, R., 2013. House/work: Home as a space of work and consumption. Geography Compass, 7(12), pp.821-831.

Cox, R., 2006. The servant problem: paid domestic work in a global economy. London, UK: I.B. Tauris.

Cox, R. and Watt, P., 2002. Globalization, polarization and the informal sector: the case of paid domestic workers in London. Area, 34(1), pp.39-47.

Cox, R. and Narula, R., 2003. Playing happy families: rules and relationships in au pair employing households in London, England. Gender, Place and Culture, 10(4), pp.333-344.

Delap, L., 2011. Knowing their place: domestic service in twentieth-century Britain. Oxford University Press.

Delap, L., 2011. Housework, Housewives, and Domestic Workers: Twentieth-Century Dilemmas of Domesticity. Home Cultures, 8(2), pp.189-209.

Delap, L., 2010. Kitchen-Sink Laughter: Domestic Service Humor in Twentieth-Century Britain. Journal of British Studies, 49(3), pp.623-654.

Delap, L., 2007. “Campaigns of Curiosity”: Class Crossing and Role Reversal in British Domestic Service, 1890-1950. Left History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Historical Inquiry and Debate, 12(2).

Hoskins, L., 2011. Stories of work and home in the mid-nineteenth century. Home Cultures, 8(2), pp.151-169.

Light, A., 2008. Mrs Woolf and the servants: the hidden heart of domestic service. Penguin UK.

Schwartz, L., 2019. Feminism and the Servant Problem. Cambridge University Press.

Show Notes

Credits

Produced by Ana Baeza Ruiz, with guests Rosie Cox and Lucy Delap

Editing by Ana Baeza, Zoë Hendon and Paul Ford Sound

Contributions from Esra Bici and Kate Murray

Music Credits

Say It Again, I’m Listening by Daniel Birch is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial License

Let that Sink In by Lee Rosevere is licensed under Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0)

Would You Change the World by Min-Y-Llan is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License.

Phase 5 by Xylo-Ziko is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License.