Relationships

10 Essentials About Midlife Love Relationships

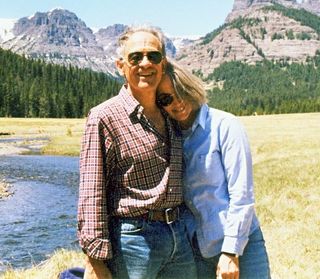

Strategies for honoring and nurturing romance over forty

Posted November 27, 2016

Sometimes age matters and sometimes it does not. Forty, fifty, or sixty years of life experience are not the same as twenty or thirty. A person’s relationship to himself or herself claims increasing attention as the body, mind, emotions and spirit require more and sometimes different care. Love relationships, often coasting along on automatic pilot, may shift in positive or painful ways, especially when hormone changes alter sexual desire, or memory patterns and shifts in vision and hearing affect communication.

Patterns once put in place to override physical, spiritual or social needs for nourishment, for rest and recovery, even for growth, can become inadequate. Bodies change and, along with those changes, so can the attention and time they require.

Household tasks can expand along with the size, composition, and changing needs of a family. Perhaps a child is involved in serious athletic or music activities; perhaps a relative has joined the household and, in addition to bringing resources into it, needs occasional support from it.

When children leave, the empty nest requires additional adaptations. At work, those born a decade or two later mature with new perspectives and ideas and we realize we are no longer the Young Turks. Career dreams may have matured or been modified.

Many of these changes arrive gradually, barely noticed by our conscious selves. At the same time, the years can bring hard-won wisdom born of struggling through our life lessons, dealing with losses and new opportunities, learning what we do and do not want, what brings pleasure and what simply clutter, what creates meaning in our lives and what makes our life feel empty.

Because we are each embedded in our own generation, we come of age into adulthood with peers who shared the culture we grew up in. We instinctively compare ourselves to those who were in school when we were, who voted in the same elections and perhaps served in the same wars, who remember the same hurricanes and earthquakes, watched the same celebrities and television shows. Those born before MTV videos hear the music of their teen years in their heads; those born after, see the videos.

Each age cohort learned its culture through similar media. They contemplated international travel, global warming, the rise or fall of divorce rates through a particular frame of reference and perhaps with different conclusions. By midlife, we no longer experience or discover the world—or ourselves—as quite the exotic place or person they once were. Both the forces of age and of our specific generation frame relationships as they evolve.

The research of Stanford psychologist Laura Carstensen can help us make sense of the changes that come as we move through our years. She has devoted her professional life to studying the near universality of midlife changes in motivation and, with them, goals. She and her colleagues coined the term “socioemotional selectivity” to describe the midlife shift, an increased tendency of people as they age to value experiences and relationships that bring positive emotions and meaning in the current moment more than novel information with its potential excitement or influences on future goals. No more networking, instead of sharing a drink with friends; or working unreasonably long hours, instead of making time for family dinners; or spending time with a colleague you don’t really care for, rather than hanging out with a neighbor whom you do.

According to socioemotional selectivity theory and data, pleasure, joy and meaning in the present begin to override pursuit of some vision that may or may not ever materialize. For example, I happily gave up my dream of piloting a plane because I cared more about providing security for my college-bound children. Physical risks and financial costs were not worth the anticipated accomplishment. Instead, I found less spectacular ways to meet and master challenges that better served the life I was in. On the other hand, for my own integrity, once my children were grown, I also realized that I needed to return to Paris. And, eventually, to write and publish a memoir, the story that began with that trip. I wanted to share it with others whom it might inspire.

As centrality of career fades, emotionally meaningful personal relationships, including romantic ones, become more important. Awareness of mortality brings an increased priority for using the time one has remaining for investing in fewer but more rewarding connections to others. Those that are not rewarding can be abandoned. Census data analyzed at Bowling Green State University showed that from 1990 to 2010 the divorce rate among couples fifty years old and over had doubled. More midlife American couples were re-evaluating their choices.

Clearly, Carstensen’s findings were more than a quirky outcome based on a specific generation who came of age during a time of turmoil. Rather, people in midlife are increasingly voting with their feet, leaving situations that no longer meet their needs and striking out into the unknown. The inevitable outcome is that more midlife people are unwed and re-wed. New personal relationships can develop, providing social support, or the benefits of closeness. And romantic love endures.

New singles who have reached midlife bring with them a history of patterns in relationships—whom they choose, how they communicate, what they expect in a partner and from a relationship. These default repetitions are unlikely to change unless some experience makes a person consciously want a different path. But, as Carstensen argues, time alone can bring just that motivation . Other dreams have been confronted and perhaps attained; the bucket list changed from a focus on excitement and discovery to one looking for connection.

By mid-life, people may have become parents, watching their own children move into adult lives. They have usually dealt with illnesses, crises, perhaps a loss of functioning in some area and the death of someone important to them. Their resilience has been tested. With awareness of mortality and the reassurance of their own survival, they come into a new love relationship with a very different perspective than that of the young man or woman who may have not yet explored the role of an intimate relationship in his or her life.

By mid-life, a person is ready to say, along with Robert Browning, “Grow old along with me; the best is yet to be.”

Lessons carried into mid-life relationships:

- This lifetime is not infinite; a search for the new, instrumental or exciting is not as emotionally rewarding as spending time with people who bring you joy, comfort, a sense of close connection, or meaning. Illness and mortality put the present in perspective.

- Loss is inevitable; you may also have learned that you are resilient enough to love in spite of the possibility of loss.

- You have made mistakes and conscious change will be necessary. Twelve-step programs have a saying, “insanity is doing the same thing in the same way and expecting the outcome to be any different”. By midlife, you know that you will need to work on new responses and habits.

- What may have been attractive to you when you were younger often requires revision as your values and goals have changed. Be sure to examine assumptions, especially about what is important in a close and/or romantic relationship, and in a person you want in your life in a meaningful way at this point in your journeys.

- Your visions of the future need to be imagined and, at the same time, they need to be considered only possibilities. Old dreams may require updating. You need to be flexible as your life unfolds; all the events you do not control are likely to change what you think is within your power.

- Moments that are meaningful become distinguished from those that are pleasurable or distracting or necessary. As reliably as a performance of the New York City Ballet can put a smile on my face or an intense bridge game can take my mind off worry about an adult child who has traveled off my radar, meaningful moments (for me) come in three varieties: sharing discovery with another person; learning something new about myself, my world, myself in the world; or being able to improve the quality of someone else's life. The first permits and then leads to acts that can nurture love of another; the second can deepen love for myself; the third allows love and meaning to flow outward.

- Places long associated with personal identity can shift to an abstract level—no longer “home” rooted in the concrete definition of a location, a community, or a career but more in aspects of the self that feel specific, unique yet grounded in the universal of meaningful connections to others. With self-knowledge can come acceptance of vulnerabilities, appreciation for desired growth, and new dreams. Allocation of resources—especially time, energy and money—is then re-evaluated.

- What one wants and needs from a close relationship can change. Agreements may need to be revisited. Some people will fade away as growth in different directions takes them down different paths and brings different interpersonal needs. New relationships can appear in your life, supporting new chapters. Hidden parts of the self may demand recognition and romance that can sustain them.

- Sometimes the burden of a relationship becomes overwhelming and what people want and need from each other cannot be revised or honored. The relationship ends; loss occurs. A new romantic relationship might feel scary, bringing threats of more loss or a rekindled fear of overwhelming burdens that come with aging.

- Everyone is rooted in his or her generation. Who are your peers and how narrowly are they defined in age and therefore culture? Perhaps relationships need to broaden to include younger and older people, as common human needs and wants supplant those sold to us by the cultures in which we are embedded.

Copyright 2016 Roni Beth Tower

Visit me at www.miracleatmidlife.com