How pioneers Hill and Adamson created startlingly modern photographs

24 May 2017

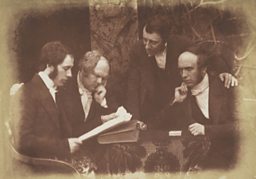

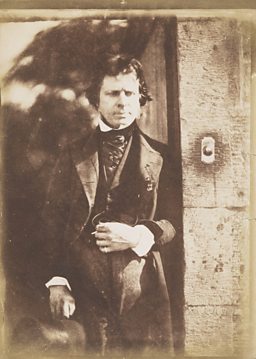

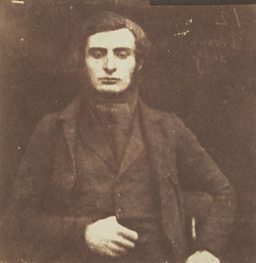

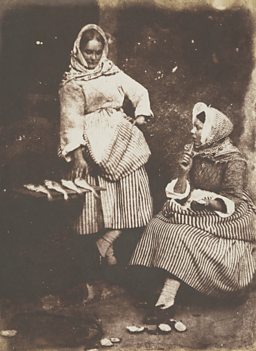

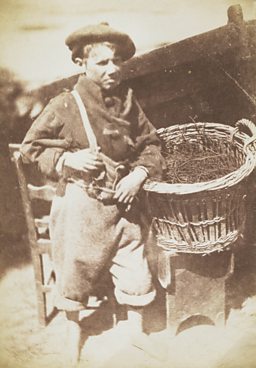

From fishwives to hung-over men, the intimate portraits of David Hill and Robert Adamson are like seeing 19th Century characters come alive. A partnership forged at the birth of photography, the Edinburgh duo turned a scientific novelty into an art form. WILLIAM COOK goes time travelling.

Here on Calton Hill, high above the historic streets of Edinburgh, there is a handsome old house which shaped the history of photography. Today Rock House is a smart rental property for prosperous holidaymakers, but for four momentous years, from 1843 to 1847, it was the home of Hill and Adamson, two Scotsmen who turned a scientific novelty into a new art form.

Photography was only a few years old when David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson founded Scotland’s first photographic studio. In 1839 a Frenchman, Louis Daguerre, had discovered a way of printing photographic images onto silver-coated copper plates. In 1840, an Englishman, William Henry Fox Talbot, had unveiled a similar process, printing ‘photogenic drawings’ onto ‘silver salted’ paper. Yet the pictures they made were staid and static – demonstrations of a new process, rather than artworks in their own right. Hill and Adamson were the first to realise the artistic potential of this invention, creating thousands of dramatic images in their studio on Calton Hill.

Photography was only a few years old when David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson founded Scotland’s first photographic studio

Ironically, the thing that brought these two men together wasn’t a scientific innovation but a religious dispute. In 1843, the Church of Scotland held its General Assembly in Edinburgh, and 400 evangelical ministers walked out, founding a new church, the Free Church of Scotland. This schism was a sensation, as divisive in its day as Brexit, or the Scottish Referendum.

David Octavius Hill was a successful painter, with an eye for newsworthy stories. He decided to paint a picture of these rebels, who’d split the Scottish church in two. However there were 400 rebels, and not nearly enough time to paint them, so he turned to his friend, the physicist David Brewster, for help.

Brewster knew a brilliant young chemist called Robert Adamson, with a keen interest in photography. Why not ask Adamson to photograph them, said Brewster. Then Hill could use these photos to paint his picture at his leisure. The two men met, and hit it off, but Hill became so enthralled by Adamson’s photographs that he forgot about his painting. They started taking photos together, and a creative partnership was born.

Hill was 41, widowed with a young daughter. Adamson was only 22, young enough to be his son. However this age gap was no obstacle. When Adamson asked Hill to move in with him, and bring his daughter with him, Hill was delighted. They lived and worked together for four happy, productive years, until Adamson died of tuberculosis aged just 26.

Hill never found another partner to replace his beloved Adamson, and more or less abandoned photography after Adamson’s untimely death (photography was a team game in those days - the process was so laborious and the equipment so unwieldy that it was difficult to do it on your own).

If Adamson had survived, who knows what else they might have done, but they achieved more in four years than most photographers manage in a lifetime. The Scottish National Portrait Gallery has thousands of their photos, and out of this collection curator Anne Lyden has assembled a stunning exhibition. “They were living and breathing photography,” she says.

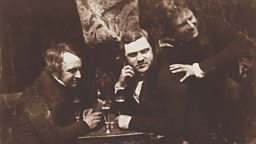

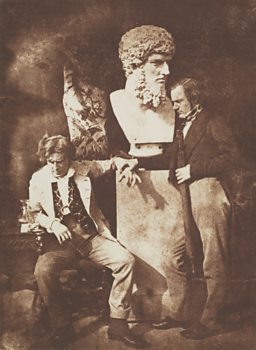

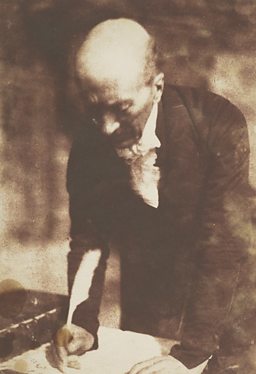

So what was so special about Hill and Adamson’s photographs? Well, the era when they made them, for one thing. Photography was still in its infancy, yet their intimate, informal portraits seem astonishingly modern – more modern than many photos taken half a century later.

Their camera is a time machine, taking us back to the days of Turner and Dickens

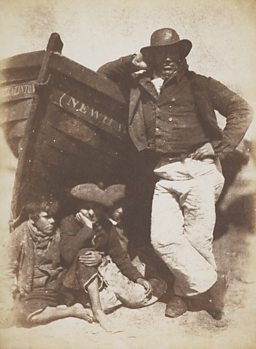

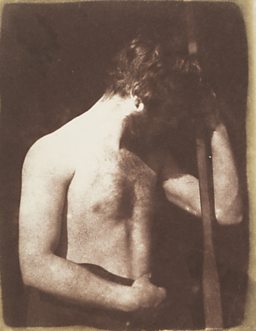

Their dramatic use of light and shade harks back to Old Masters like Rembrandt, but above all their art looks forward, towards the 20th Century. Their stark portraits of Newhaven fisherfolk feel incredibly contemporary. “There’s a sense of them living and breathing, of being flesh and blood,” says Anne.

The other thing that’s so striking is the way their photographs were made. Modern photos lie flat upon the surface of the paper. These ‘salt and silver’ images are imbedded in thick fibrous paper, giving them a painterly sense of depth. “They have a physical property that digital photographs don’t have,” Anne tells me. “They have an ability to speak to us today.”

The cumbersome production process was another asset, in a way. Working outdoors, in bright sunshine, with extraordinarily long exposures, they had to choose bold and simple images, giving their pictures a rugged clarity which more modern photos often lack.

Their camera is a time machine, taking us back to the days of Turner and Dickens. It’s incredible to think that many of their subjects were born way back in the 18th Century.

“They’re working right at the very beginning of photography,” explains Anne, over coffee at Rock House. “It’s only four years since photography’s been announced to the world, yet they’re already producing highly naturalistic, beautiful portraits that still resonate with us today.”

They were also working in a dynamic metropolis, at a time of tremendous change. Then as now, Edinburgh was an important seat of learning - a centre of the arts and sciences and a forum for intense debate. At Rock House they photographed the great thinkers of their age. “People who were changing the course of history were sitting before their camera.”

Steam trains and the penny post brought the world to Edinburgh. Hill and Adamson could travel all over Britain, and send their photos across the globe. Today there are collections of their work worldwide, but Edinburgh’s is the largest, and this new show, A Perfect Chemistry, is a landmark retrospective.

The biggest exhibit is a huge painting, The First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, which Hill finally finished in 1866, 18 years after Adamson’s death. It’s an impressive artwork, but it’s not a patch on their vivid photographs, which will live on long after this workmanlike painting has been forgotten.

A Perfect Chemistry: Photography by Hill & Adamson is at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, from 27 May to 1 October 2017.

All images by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland.

-

![]()

How well do you know your British photography?

From iconic moments of World War One to the polarising work of Martin Parr... take the quiz.

-

![]()

Confronting the one per cent

Glaswegian photographer snaps London's super-rich

-

![]()

Photographing the Heysel disaster

Britain in Focus presenter Eamonn McCabe on the football match where everything changed

-

![]()

Preview Photography season

Watch the trailer for BBC Four's Photography season

-

![]()

Photography season on BBC Four

Explore the past, present and future of photography

-

![]()

Life through a lens

10 great photography features from BBC Arts

-

![]()

When music mattered

The stories behind 10 great rock photographs by Michael Zagaris

-

![]()

Works of heart

15 emotive images from the Magnum vault

-

![]()

Chasing outlaws

How Danny Lyon's images of American outsiders changed photography

-

![]()

Rock Against Racism

Syd Shelton looks back on his work documenting the anti-racist organisation

-

![]()

Best pictures

Capturing the Oscars' golden moments with Marlon, Audrey and Jack

-

![]()

Bob Marley, John Lydon and me

Photographer Dennis Morris on capturing the punky reggae party in the late 1970s

-

![]()

Positive force

The pioneering early photography of Julia Margaret Cameron

-

![]()

Life in colour

Colour photojournalism pioneer John Bulmer's world view

-

![]()

Covering crisis and conflict

Steve McCurry reflects on his 30-year career in photography

-

![]()

The world on film

All photography features from BBC Arts

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms