Down in the Valley

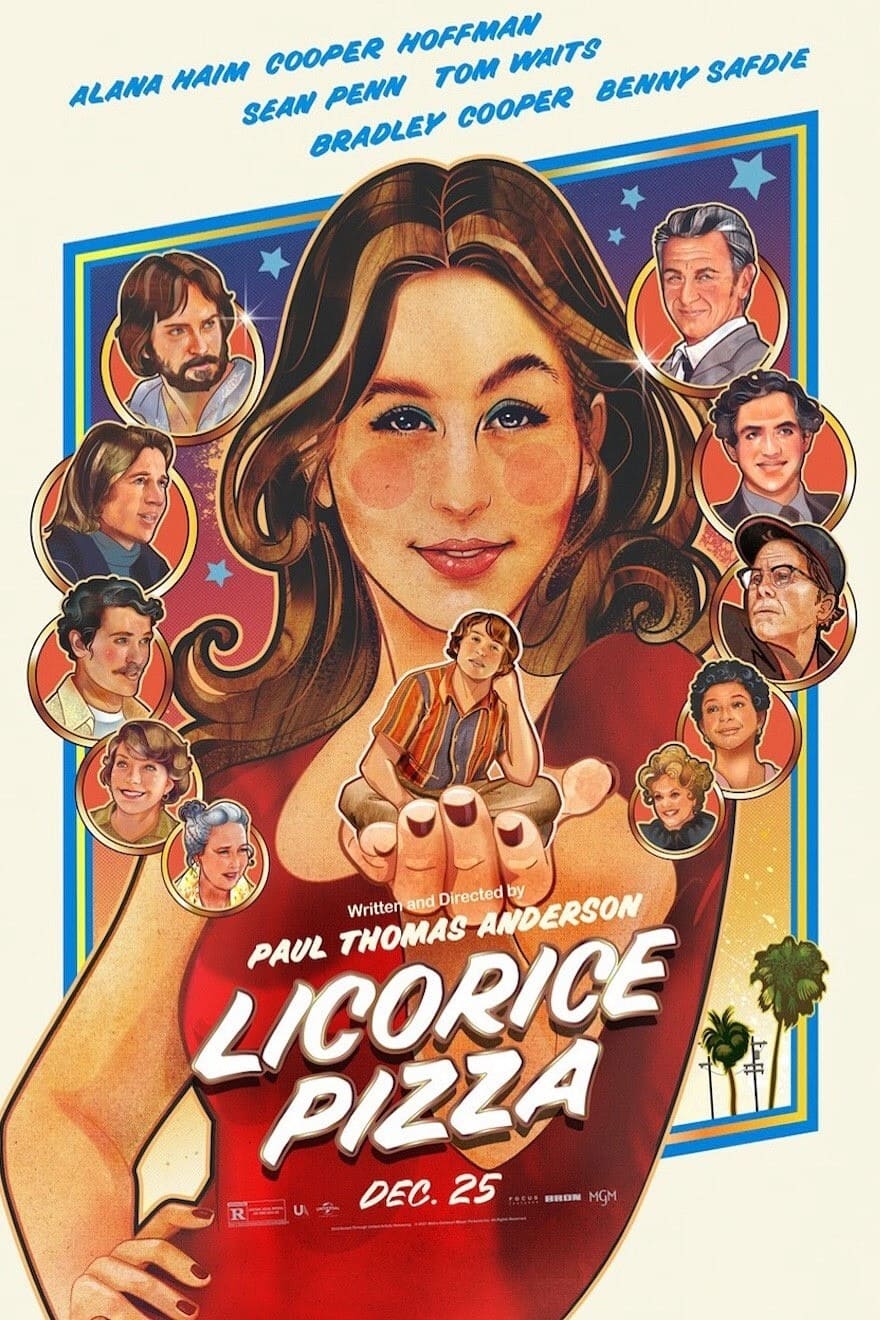

Insofar as we should always sit up and take notice when a major film director produces an obviously intimate and personal work, then yes, we should absolute bow in the direction of Licorice Pizza. The ninth feature directed by Paul Thomas Anderson - who is, by any measure, a major director - isn't a work of autobiography as such (indeed, it is much more directly based on the extraordinary youth of Anderson's friend, child actor-turned-adolescent huckster-turned-adult film producer* Gary Goetzman), but it comes out of an autobiographical place. Very much like Quentin Tarantino's 2019 nostalgia epic Once Upon a Time ...in Hollywood, Licorice Pizza is far more about inhabiting the spirit of a place and time when the writer-director was young than it is about anything else. Its cryptic title is borrowed from a chain of record stores throughout southern California that was absorbed into Sam Goody in the mid-1980s, but which, to Anderson anyway, had its heyday a good decade or more earlier, leading to a strong emotional tug that is, I am entirely certain, quite irresistible to those of a certain age and from a certain part of the world, even if it is almost comically devoid of meaning to the rest of us.

Anyway, my point: Licorice Pizza is obviously a deeply felt movie pulled from the warmest recesses of the director's heart, and thus a major work by pretty much any standard. And this is not the less true just because I really didn't like the thing at all. I don't count, after all; Anderson has a pretty low hit rate with me, so a film that is, in a sense, the most Anderson of all was coming in at a prohibitive disadvantage. But that doesn't change the fact that, as much as I acknowledge the loving place this movie came from, I found it almost unrelentingly tedious, or even altogether insufferable.

"Almost" unrelenting, because the film has one unabashed strength that I greatly admired, somewhat to my surprise: it has a remarkably interesting look. Anderson served as his own cinematographer for a second consecutive feature, following 2017's Phantom Thread, sharing credit with Michael Bauman, who was credited as the lighting cameraman on that film, and has never before this had a cinematographer credit on a feature at all. Which is to say, we're looking at a film shot by two people who are largely untested in this craft; not that they're bumbling neophytes (Bauman has gaffing and electrical credits stretching back to the 1990s), but they come to the film unburdened by concerns like "this is how I prefer to do things", and truly, you can feel that in the very appealingly smudgy, fuzzed-out images, encased in a warm blanket in grain, that make up the most unmistakably shot-on-film movie of 2021.

It's almost fair to say that Licorice Pizza is "ugly", if we are being honest, but it's the scruffy, lovable kind of ugliness that feels cozy and casual. The film is set in 1973, part of the most visually ugly period in the history of the United States of America, and so a certain grungy, washed-out look just feels so good; even more than the lovingly obsessed-over production design, by Florencia Martin, and costume design, by Mark Bridges, I think it's that entrancingly overlit, earthtone look in the cinematography that really makes Licorice Pizza "feel" like the '70s, or at least the version of the '70s that floats through the pop cultural consciousness. I can't lie; I loved it.

How I wished I loved anything that was being filmed. The scruffy, ultra-casual, "who gives a shit if everything is kind of shaggy and rough" vibe that feeds the cinematography feeds literally every other aspect of the film as well. Anderson is no stranger to shaggy storytelling: the closest to a direct analogue for Licorice Pizza in his filmography is 2014's Inherent Vice, an ambling bit of nonsense that barely even tries to hold together as a focused narrative. But "barely even trying" would be overstating how much narrative momentum Licorice Pizza possesses: its languid 133-minute running time is almost exclusively dedicated to watching people hanging out in individual moments, with an almost defiant refusal to make connections between its oh-so-loosely-defined "acts".

The main hangers-out are Gary (Cooper Hoffman), a 15-year-old child actor who has hit his teenage years with enough of a vengeance that it's starting to make it hard to cast him, not least because he's an arrogant little shit; but he's also a born huckster who comes up with a new business venture on the order of every few weeks, and in the lackadaisical world of the San Fernando Valley in the early '70s, he's even got a pretty open path to pursuing those ventures. The other is Alana (Alana Haim), a 25-year-old whose life is pretty well stalled-out; she's working a crap job taking high school photos when we meet her, and that's also when Gary meets her, and with the brash egoism of a charming brat who has never once been told "no" and probably wouldn't understand the word if he had been, decides to fall head over heels in love with her. For the rest of the movie, he's trying like a maniac to make her think he's cool, and given her bottomless self-doubt, she overcomes the voice in her brain screaming not to encourage this, because it's pretty clearly the only positive attention she gets over the course of an average week. The film doesn't precisely endorse this, but even less does it condemn this, and so it has gotten itself hung up in a small controversy that, to be fair, it did absolutely nothing to forestall despite it being extremely predictable.

I have no real opinion one way or the other, mostly because I just didn't really like hanging out with Gary and Alana, so I don't really care if they represent something toxic and immoral. The represent something much worse: a waste of my time. The thing about Licorice Pizza, as I'm sure its most rhapsodic fans would happily admit to (there are a lot of them), is that it's a "vibe" movie. You go in, you feel its hazy sensibility, the attitudes of its characters - not just Gary and Alana, the whole universe of colorful figures Anderson has whipped up with a giant cast made out of many people he's close personal friends with (such as, in fact, Hoffman, the son of his late friend and generation-defining talent Philip Seymour Hoffman; and Haim, the youngest of three sister making up the rock band Haim, whose family and Anderson's have been tangled up for years and years) - you sink into that sensibility and those attitudes, and you just ride with it. Anderson has, to some extent, been striving to make this movie almost his whole career: all seven of his films that don't star Daniel Day-Lewis are to some extent or another mostly about just feeling those vibes from the characters and actors, taking in the moment, living in it, enjoying it. And that's great if you can catch those vibes. I've never really been able to, with Anderson, and I don't think I've ever come further than with Licorice Pizza. As far as I can tell, it's not really doing anything to encourage getting on its wavelength; it's just kind of happening, idly and breezily, and you're either there or you're not.

If you're not, as I wasn't, the film is a monstrous, grim-faced trudge through scene after scene after scene of Anderson's famous friends shambling out and riffing. Here's Bradley Cooper, giving everything he's got to playing a parody of Jon Peters, semi-notorious film producer and asshole, as a kind of dark mirror to Gary's guileless egoism. Here's Maya Rudolph, Mrs. Anderson herself, popping up to wave and say hi for about three seconds (almost nobody whose name you'd recognise shows up for more than two or three scenes). Here's a more or less complete absence of any development, though the last third of the movie at least starts to amplify Alana's growing disgust at the life she's letting herself relax into, and that sort of gives it the rough shape of a character arc. Though all of this is pitched into the dustbin by a final two minutes that are just stunningly misjudged.

Compounding all of this, neither Haim nor Hoffman ever really sell themselves as anything but what they are: first-time actors being given the entire weight of a movie to bear by a director who very obviously thinks they're doing great, just great, and so does not really do anything to shape their performances. Haim is trying harder, which cuts both ways: she produces moments where it actually feels like Alana has real inner feelings that give her a lot of discomfort and guilt (and, rarely, pride), but there are also moments where she over-enunciates her lines and severely over-stresses her emotions in the fashion of, well, an enthusiastic amateur, who would have benefited a lot from being told "okay, what if we try it this way?" more often. Hoffman, who apparently has no real designs on being an actor, is really and truly just hanging out, flashing a self-satisfied grin as very nearly his only discernible "choice".

With those two performances driving it, Licorice Pizza ends up feeling very, just, there. But it's not the actors' fault; people with much more mileage are giving basically the same performances. In fact, the only person in the whole cast who struck me as actually trying to do something, weighing her lines and putting readings on them that push into unexpected territory, letting the too-close close-ups work for her rather than just pinning her down, is Harriet Sansom Harris as a flamboyantly unctuous agent - present in all of one scene, but it's memorable and electric and alive. I also mostly liked what Benny Safdie was up to as real-life politician Joel Wachs, though he benefits from having the only character in the entire movie besides Alana who actual has complicated internalised conflicts written into the script.

(Honesty forces me to admit that John Michael Higgins is doing something as well, but what he's doing is so surreally misconceived, both by him and his director, that I would be happier blotting it from my mind).

And the film is very confidently made; it looks casual and formless, but in an extremely precise, manicured way, and this is true right from its grand opening gesture of a long tracking shot in and out of the high school where Alana is plying her miserable trade, an elaborate show-off technique that's used in the film to seem particularly random and off-the-cuff, as the camera seems to just randomly latch onto Alana and Gary as the people to follow. And it progresses past the impeccable design, and the carefully curated list of songs creating a wide array of what one might bump into in 1973, not all of it new, not all of it hip, all the way to the crisp editing that manages to keep things feeling loose even as every cut is very deliberately moving us through this apparently shapeless moments.

So I can't hate the film; it is a very well-made version of what it wants to be. I just find what it wants to be totally alienating and completely without interest. That's my problem, of course, but I don't think that anyone could claim that Licorice Pizza is trying at all to win its audience over. It's just sitting there, vibing, and while I don't want to take that away from the people vibing with it, I also can't say that strikes me as an especially ambitious or admirable way to go about the business of storytelling.

*That is, a film producer who is an adult, not a producer who mainly works in pornography. In fact, quite an estimable film producer who is an adult, having been involved with a few of the more important Jonathan Demme pictures, and several Tom Hanks projects.

Anyway, my point: Licorice Pizza is obviously a deeply felt movie pulled from the warmest recesses of the director's heart, and thus a major work by pretty much any standard. And this is not the less true just because I really didn't like the thing at all. I don't count, after all; Anderson has a pretty low hit rate with me, so a film that is, in a sense, the most Anderson of all was coming in at a prohibitive disadvantage. But that doesn't change the fact that, as much as I acknowledge the loving place this movie came from, I found it almost unrelentingly tedious, or even altogether insufferable.

"Almost" unrelenting, because the film has one unabashed strength that I greatly admired, somewhat to my surprise: it has a remarkably interesting look. Anderson served as his own cinematographer for a second consecutive feature, following 2017's Phantom Thread, sharing credit with Michael Bauman, who was credited as the lighting cameraman on that film, and has never before this had a cinematographer credit on a feature at all. Which is to say, we're looking at a film shot by two people who are largely untested in this craft; not that they're bumbling neophytes (Bauman has gaffing and electrical credits stretching back to the 1990s), but they come to the film unburdened by concerns like "this is how I prefer to do things", and truly, you can feel that in the very appealingly smudgy, fuzzed-out images, encased in a warm blanket in grain, that make up the most unmistakably shot-on-film movie of 2021.

It's almost fair to say that Licorice Pizza is "ugly", if we are being honest, but it's the scruffy, lovable kind of ugliness that feels cozy and casual. The film is set in 1973, part of the most visually ugly period in the history of the United States of America, and so a certain grungy, washed-out look just feels so good; even more than the lovingly obsessed-over production design, by Florencia Martin, and costume design, by Mark Bridges, I think it's that entrancingly overlit, earthtone look in the cinematography that really makes Licorice Pizza "feel" like the '70s, or at least the version of the '70s that floats through the pop cultural consciousness. I can't lie; I loved it.

How I wished I loved anything that was being filmed. The scruffy, ultra-casual, "who gives a shit if everything is kind of shaggy and rough" vibe that feeds the cinematography feeds literally every other aspect of the film as well. Anderson is no stranger to shaggy storytelling: the closest to a direct analogue for Licorice Pizza in his filmography is 2014's Inherent Vice, an ambling bit of nonsense that barely even tries to hold together as a focused narrative. But "barely even trying" would be overstating how much narrative momentum Licorice Pizza possesses: its languid 133-minute running time is almost exclusively dedicated to watching people hanging out in individual moments, with an almost defiant refusal to make connections between its oh-so-loosely-defined "acts".

The main hangers-out are Gary (Cooper Hoffman), a 15-year-old child actor who has hit his teenage years with enough of a vengeance that it's starting to make it hard to cast him, not least because he's an arrogant little shit; but he's also a born huckster who comes up with a new business venture on the order of every few weeks, and in the lackadaisical world of the San Fernando Valley in the early '70s, he's even got a pretty open path to pursuing those ventures. The other is Alana (Alana Haim), a 25-year-old whose life is pretty well stalled-out; she's working a crap job taking high school photos when we meet her, and that's also when Gary meets her, and with the brash egoism of a charming brat who has never once been told "no" and probably wouldn't understand the word if he had been, decides to fall head over heels in love with her. For the rest of the movie, he's trying like a maniac to make her think he's cool, and given her bottomless self-doubt, she overcomes the voice in her brain screaming not to encourage this, because it's pretty clearly the only positive attention she gets over the course of an average week. The film doesn't precisely endorse this, but even less does it condemn this, and so it has gotten itself hung up in a small controversy that, to be fair, it did absolutely nothing to forestall despite it being extremely predictable.

I have no real opinion one way or the other, mostly because I just didn't really like hanging out with Gary and Alana, so I don't really care if they represent something toxic and immoral. The represent something much worse: a waste of my time. The thing about Licorice Pizza, as I'm sure its most rhapsodic fans would happily admit to (there are a lot of them), is that it's a "vibe" movie. You go in, you feel its hazy sensibility, the attitudes of its characters - not just Gary and Alana, the whole universe of colorful figures Anderson has whipped up with a giant cast made out of many people he's close personal friends with (such as, in fact, Hoffman, the son of his late friend and generation-defining talent Philip Seymour Hoffman; and Haim, the youngest of three sister making up the rock band Haim, whose family and Anderson's have been tangled up for years and years) - you sink into that sensibility and those attitudes, and you just ride with it. Anderson has, to some extent, been striving to make this movie almost his whole career: all seven of his films that don't star Daniel Day-Lewis are to some extent or another mostly about just feeling those vibes from the characters and actors, taking in the moment, living in it, enjoying it. And that's great if you can catch those vibes. I've never really been able to, with Anderson, and I don't think I've ever come further than with Licorice Pizza. As far as I can tell, it's not really doing anything to encourage getting on its wavelength; it's just kind of happening, idly and breezily, and you're either there or you're not.

If you're not, as I wasn't, the film is a monstrous, grim-faced trudge through scene after scene after scene of Anderson's famous friends shambling out and riffing. Here's Bradley Cooper, giving everything he's got to playing a parody of Jon Peters, semi-notorious film producer and asshole, as a kind of dark mirror to Gary's guileless egoism. Here's Maya Rudolph, Mrs. Anderson herself, popping up to wave and say hi for about three seconds (almost nobody whose name you'd recognise shows up for more than two or three scenes). Here's a more or less complete absence of any development, though the last third of the movie at least starts to amplify Alana's growing disgust at the life she's letting herself relax into, and that sort of gives it the rough shape of a character arc. Though all of this is pitched into the dustbin by a final two minutes that are just stunningly misjudged.

Compounding all of this, neither Haim nor Hoffman ever really sell themselves as anything but what they are: first-time actors being given the entire weight of a movie to bear by a director who very obviously thinks they're doing great, just great, and so does not really do anything to shape their performances. Haim is trying harder, which cuts both ways: she produces moments where it actually feels like Alana has real inner feelings that give her a lot of discomfort and guilt (and, rarely, pride), but there are also moments where she over-enunciates her lines and severely over-stresses her emotions in the fashion of, well, an enthusiastic amateur, who would have benefited a lot from being told "okay, what if we try it this way?" more often. Hoffman, who apparently has no real designs on being an actor, is really and truly just hanging out, flashing a self-satisfied grin as very nearly his only discernible "choice".

With those two performances driving it, Licorice Pizza ends up feeling very, just, there. But it's not the actors' fault; people with much more mileage are giving basically the same performances. In fact, the only person in the whole cast who struck me as actually trying to do something, weighing her lines and putting readings on them that push into unexpected territory, letting the too-close close-ups work for her rather than just pinning her down, is Harriet Sansom Harris as a flamboyantly unctuous agent - present in all of one scene, but it's memorable and electric and alive. I also mostly liked what Benny Safdie was up to as real-life politician Joel Wachs, though he benefits from having the only character in the entire movie besides Alana who actual has complicated internalised conflicts written into the script.

(Honesty forces me to admit that John Michael Higgins is doing something as well, but what he's doing is so surreally misconceived, both by him and his director, that I would be happier blotting it from my mind).

And the film is very confidently made; it looks casual and formless, but in an extremely precise, manicured way, and this is true right from its grand opening gesture of a long tracking shot in and out of the high school where Alana is plying her miserable trade, an elaborate show-off technique that's used in the film to seem particularly random and off-the-cuff, as the camera seems to just randomly latch onto Alana and Gary as the people to follow. And it progresses past the impeccable design, and the carefully curated list of songs creating a wide array of what one might bump into in 1973, not all of it new, not all of it hip, all the way to the crisp editing that manages to keep things feeling loose even as every cut is very deliberately moving us through this apparently shapeless moments.

So I can't hate the film; it is a very well-made version of what it wants to be. I just find what it wants to be totally alienating and completely without interest. That's my problem, of course, but I don't think that anyone could claim that Licorice Pizza is trying at all to win its audience over. It's just sitting there, vibing, and while I don't want to take that away from the people vibing with it, I also can't say that strikes me as an especially ambitious or admirable way to go about the business of storytelling.

*That is, a film producer who is an adult, not a producer who mainly works in pornography. In fact, quite an estimable film producer who is an adult, having been involved with a few of the more important Jonathan Demme pictures, and several Tom Hanks projects.