Ynes Mexia

Ynés Enriquetta Julietta Mexía | |

|---|---|

| Ynés Mexía | |

| |

| Born | May 24, 1870 Washington, D.C., United States |

| Died | July 12, 1938 (aged 68) Berkeley, California, United States |

| Nationality | Mexican, American |

| Citizenship | United States Mexico |

| Alma mater | University of California, Berkeley |

| Awards | Life member of the California Academy of Sciences |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Mexia |

Ynés Enriquetta Julietta Mexía (May 24, 1870 – July 12, 1938) was a Mexican-American botanist notable for her extensive collection of novel specimens of flora and plants originating from sites in Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. She discovered a new genus of Asteraceae, known after her as Mexianthus, and accumulated over 150,000 specimens for botanical study[1] over the course of a career spanning 16 years enduring challenges in the field that included poisonous berries, dangerous terrain, bogs and earthquakes for the sake of her research.[2]

Biography[edit]

Ynés Mexía was born on May 24, 1870, in Washington D.C. to Enrique Mexia, a Mexican diplomat, and Sarah Wilmer Mexía.[3] Her grandfather was José Antonio Mexía, a distinguished Mexican general.[1] Sarah Wilmer was related to Samuel Eccleston, the fifth Catholic Archbishop of Baltimore.[4]

In 1873, her father returned to Mexico, and her mother moved Ynés and her six half-siblings to a ranch in Limestone, Texas, later to be called Mexia.[1][5] Later, the family moved around in various eastern cities such as Philadelphia and Ontario, where she received a private school education.[6] They settled in Maryland, where Ynés attended St. Joseph's Preparatory School in Emmittsburg.[1] In 1887, she moved to Mexico where she remained with her father for ten years.[1][2][7]

While residing there in 1897, Mexia married her first husband, Herman de Laue, a Spanish-German merchant, who died in 1904.[8][9][5] Around the time of his death, Mexia started Quinta, a pet and poultry stock raising business, at the hacienda she inherited from her father's estate.[10] Later, she married D. Augustin Reygados, but the union ended in divorce in 1906, after he effectively bankrupted the business.[8][5][11][10]

In 1909, at the age of 39, Mexía suffered a mental and physical breakdown and left Mexico for San Francisco in search of medical care.[2] She was treated by Dr. Philip King Brown, founder of the Arequipa Sanatorium in Fairfax,[12] for a total of ten years.[13] While in Northern California, Mexía began going on excursions with the Sierra Club into the mountains, and thus became interested in the region's ecology such as redwoods, birds, and plants.[2]

In 1924 Mexía became a United States citizen.[14]

Ynés wrote to Alice Eastwood in July 1925, advising Eastwood that she was about to accompany Stanford's Assistant Herbarium Curator, Roxanna Ferris, on a collecting trip to Mexico, which would be her first botanical exploration in that country.[3] In middle age, Mexía had found her purpose in life, writing: "… I have a job, [where] I produce something real and lasting."[14]

Over the course of the next 13 years, Mexía traveled from the northern regions of Alaska to the southern tip of Tierra del Fuego. Her habits often surprised people she met because she was not acting in a manner typical of a woman of the early 20th century: traveling alone, riding horseback, wearing trousers (knickers), and preferring to sleep outside even if beds or indoor accommodations were available.[2] She wrote about her rejecting of such stereotypes and commented that "A well-known collector and explorer stated very positively that 'it was impossible for a woman to travel alone in Latin America,'"[2] and emphasized that "I decided that if I wanted to become better acquainted with the South American continent the best way would be to make my way right across it."[2][11]

In 1938, while on an expedition to Oaxaca, Mexico, Mexía became ill. Forced to abort the trip and return to the United States, she was subsequently diagnosed with lung cancer and died a month later at the age of 68.[2] William E. Colby, then secretary of the Sierra Club, wrote, "All who knew Ynés Mexía could not fail to be impressed by her friendly unassuming spirit, and by that rare courage which enabled her to travel, much of the time alone, in lands where few would dare to follow."[2][11]

Career[edit]

Mexía began her career in botany in 1922 when she joined an expedition led by Mr. E. L. Furlong, the Curator of Paleontology at University of California, Berkeley.[6] Her successes started to mount in 1925 with a two-month excursion to western Mexico under the auspices of Roxanna Ferris, a botanist at Stanford University.[9] Mexía fell off a cliff, fracturing ribs and injuring a hand.[9][14] Despite the trip being halted, it yielded 500 botanical specimens, including several new species. The first species to be named after Mexia, Mimosa mexiae, was discovered on this voyage, and was dedicated to her by Joseph Nelson Rose.[9][10] Various other species that she discovered were later named for her, including a flowering plant that is a member of the daisy family called Zexmenia mexiae, now named Lasianthaea macrocephala.[15] She collected the type specimen of Mexianthus in December 1926, south of Puerto Vallarta.[16]

In 1928 she was hired to collect plants in Mount McKinley National Park in Alaska, which yielded 6100 specimens.[6] The next year she went to South America and travelled by canoe down the Amazon River, covering 4,800 kilometers in two and a half years, ending at its source in the Andes.[17] This expedition resulted in 65,000 specimens.[6] On that expedition she spent three months living with the Araguarunas,[A] a native group in the Amazon.[18] During this trip she was briefly accompanied by her contemporary Mary Agnes Chase. While in Ecuador, Mexía worked with the Bureau of Plant Industry and Exploration, under the Department of Agriculture.[19] Her work focused on the cinchona or wax palm, and specific herbs that bind to the soil.[19]

In personal correspondence from 1980, the botanist John Thomas Howell refers to Mexía as a "close friend of Alice Eastwood." He relates that "In 1933 she accompanied Miss Eastwood and me on the first Eastwood and Howell collecting expedition.….in an open Model T Ford, that traversed parts of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and California...and netted over 1300 collection numbers... Mrs. Mexía was to me a dear good friend."[3]

Nina Floy Bracelin served as Mexía's collection manager[14] In her will, Mexía left sufficient money to the California Academy of Sciences to hire Bracelin as an assistant to Alice Eastwood.[14][10]

All of her research and collecting excursions were funded by the sale of her specimens to institutions and private collectors.[20]

Documentation of her expeditions appeared regularly in The Gull, the newsletter of the Audubon Society of the Pacific, from 1926 to 1935.[21][22] The Sierra Club Bulletin Archived 2019-02-26 at the Wayback Machine published two accounts of her travels: "Three Thousand Miles up the Amazon" (SCB, 18:1 [1933], 88–96),[23] and "Camping on the Equator" (SCB, 22:1 [1937], 85–91).[23] Several additional were published in Madrono, the journal of the California Botanical Society.[24]

Mexía was an active member of many scientific societies, including the California Botanical Society which she joined in 1915, the Sierra Club, the Audubon Association of the Pacific, the Sociedad Geográfica de Lima, and the California Academy of Sciences. She was also an honorary member of the Departamento Forestal, de Caza y Pesca de Mexico.[6] She also guest appeared as a lecturer at various scientific organizations in the San Francisco Bay Area on account of her riveting accounts of her journeys and her skillful photography lending visuals to her content. Her specimens are housed at the California Academy of Sciences (main collection), the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, the Field Museum of Natural History, the Gray Herbarium, the New York Botanical Garden, the Smithsonian Institution, the University of California, Berkeley, and the U.S. National Arboretum, as well as several museums and botanical gardens throughout Europe. Her personal papers are preserved at the California Academy of Sciences and at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley.[3]

Accomplishments and legacy[edit]

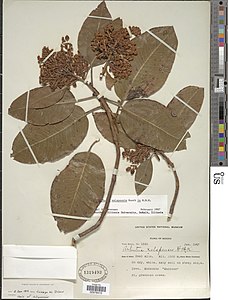

- Example specimens collected by Ynés Mexía

Mexía was atypical for a botanist or botanical collector of her era, as a woman, a person of Mexican heritage under-represented in her field, and an older person who had begun her career in her mid-fifties.[2] Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis, a professor of the history of science at the University of Florida, explains that:

"Women were actively dissuaded from doing that kind of work, because it was considered unfeminine and dangerous," says . "You actually have to camp out, you couldn’t wash your hair, you were living a kind of rough life, and that could be dangerous…. But Mexía had agency. She was doing exactly the work that she wanted to do."[2]

Mexía had a lifetime membership in the California Academy of Sciences and published a book, Brazilian Ferns Collected by Ynés Mexía, with Edwin Bingham Copeland, in 1932.[25]

Though Mexía had a short professional career—only 13 years—compared to many other academics, she collected a huge number of plant specimens. According to the British Natural History museum, she collected at least 145,000 plant specimens during her travels,[17] 500 of which were new species (mostly spermatophytes).[22] There have been at least two new genera Mexianthus mexicanus Robinson (Compositae) and Spumula quadrifida (Pucciniaceae) have been described from her work.[6] During her first expedition, she collected 500 specimens, which is the same number collected during Darwin's voyage on the Beagle.[21] Although curators are still working to catalogue her full selection of specimens, 50 new species have already been named after her.[17][21]

Mexía is remembered by her colleagues for her expertise in fieldwork, resilience in the face of difficult and dangerous conditions, as well as her impulsiveness and fractious but generous personality.[9][26] She was known and praised for her meticulous, exacting work and her skills as a botanical collector.[20]

Other researchers benefited from her knowledge of Central and South American culture and natural environment and her fluency with the Spanish language.[27] Thomas Harper Goodspeed, botanist and former director of the University of California Botanical Garden, travelled with Mexía to the Andes mountains, and commented that "the advice and information she gave us concerning primitive life in the Andes and how to become adjusted to it was invaluable."[27]

A large portion of her estate was left to the Sierra Club and the Save the Redwoods League to further environmental conservation.[2] It was Mexía who provided funding for Vernon Orlando Bailey to create and produce his pioneering invention of more humane traps for animals.[14][10]

Google Doodle[edit]

Mexía's legacy was recognized in the Google Doodle for September 15, 2019.[28][15]

PBS Short Documentary[edit]

In 2020, the life of Ynés Mexía was featured in a documentary short included in the Unladylike2020 series produced by WNET for the PBS.[13]

Publications[edit]

- Botanical Trails in Old Mexico (1929)

- Plant lists, Brazil, Mexico, and South America. (1930)

- Brazilian ferns collected by Ynes Mexia. With Edwin Bingham Copeland. Editor University Press (1932)

- Three Thousand Miles up the Amazon (1933)

- Mrs. Ynes Mexiás Route in Ecuador, 1934-1935 (1936)

- Camping on the Equator (1937)

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Aguaruna" and "Araguaruna" seem to be used interchangeably in the botanical and ethnographic literatures. E.g., from the bibliography of Folk taxonomy and evolutionary dynamics of cassava: A case study in Ubatuba, Brazil (underlining added):

- BOSTER, J.S. Classification, cultivation, and selection of Araguaruna cultivars of Manihot esculenta (Euphorbiaceae). Advances in Economic Botany, v.1, p.34-47, 1984.

- BOSTER, J.S. Selection for perceptual distinctiveness: evidence from Aguaruna cultivars of Manihot esculenta. Economic Botany, v.39, n.3, p.310-325, 1985.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Newton, David E. (2007). Latinos in science, math, and professions. New York: Facts on File. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8160-6385-7. OCLC 69679980.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l News (2019-09-15). "Ynés Mexía: Google Doodle Honors tenacious Mexican-American and explorer". Canada Journal - News of the World. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d "Research Archive Cal Academy" (PDF).

- ^ "TSHA | Mexía de Reygades, Ynés". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ a b c "Women in Science: Ynes Mexia 1870-1938". Daily Kos. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ a b c d e f Bracelin, H. P. (October 1938). "YNES MEXIA". Madroño. 4 (8): 273–275. JSTOR 41423462 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Late Bloomer: The Short, Prolific Career of Ynes Mexia". Science Talk Archive. 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- ^ a b Ogilvie & Harvey 2000, pp. 889–90.

- ^ a b c d e Yount 1999, pp. 150–51.

- ^ a b c d e Bonta, Marcia (1991). Women in the Field: America's Pioneering Women Naturalists. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 103–114. ISBN 0890964890.

- ^ a b c Siber, Kate (2019-02-20). "This Trailblazing Plant Collector Found Solace in Nature". Outside Online. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "PCAD - Arequipa Sanatorium, Fairfax, CA". pcad.lib.washington.edu. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ a b "Ynés Mexía". UNLADYLIKE2020. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ynes Mexia | Latino Natural History". latinonaturalhistory.biodiversityexhibition.com. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ a b Harmeet Kaur (15 September 2019). "Google Doodle celebrates Mexican-American botanist and explorer Ynés Mexía". CNN. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ "Type of Mexianthus mexicanus B.L. Rob. [family ASTERACEAE] on JSTOR". plants.jstor.org. Retrieved 2020-10-10.

- ^ a b c Shor, Elizabeth Noble (2000). "Mexia, Ynes Enriquetta Julietta (1870-1938) on JSTOR". plants.jstor.org. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1302002. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ McLoone 1997, pp. 23–30.

- ^ a b Mongillo & Booth 2001, pp. 179–80.

- ^ a b Petrusso 1999, pp. 391–92.

- ^ a b c Serrato Marks, Gabriela (4 May 2018). "Meet Ynes Mexia, late-blooming botanist whose adventures rivaled Darwin's". massivesci.com. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- ^ a b "Ynes Mexia collection, 1918-1966". University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ a b "Sierra Club Bulletin - History - Sierra Club". vault.sierraclub.org. Archived from the original on 2019-02-26. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ "California Botanical Society". calbotsoc.org. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ Mexia, Ynes (1932). Brazilian Ferns Collected by Ynes Mexia. Berkeley: The University of California Press.

- ^ Bailey 1994, pp. 248–49.

- ^ a b Yount, Lisa (2008). A to Z of women in science and math (Rev. ed.). New York: Facts On File. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-8160-6695-7. OCLC 144330722.

- ^ "Celebrating Ynés Mexía". www.google.com. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Mexia.

Bibliography[edit]

- Anema, Durlynn (2019), The Perfect Specimen: The 20th Century Renown Botanist--Ynes Mexia, National Writers Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0-88100-170-9

- Bailey, Martha J. (1994), American Women in Science, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 0-87436-740-9

- Bonta, Marcia (1991), Women in the Field: America's Pioneering Women Naturalists, Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0-89096-467-X

- McLoone, Margo (1997), Women Explorers in North and South America, Capstone, ISBN 978-1560655077

- Mongillo, John; Booth, Bibi (2001), Environmental Activists, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0313308845

- Oakes, Elizabeth H. (2002), International Encyclopedia of Women Scientists, Facts On File, Inc., ISBN 0-8160-4381-7

- Ogilvie, Marilyn; Harvey, Joy (2000), "Ynes Mexia", The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science, ISBN 0-415-92038-8

- Petrusso, Annette (1999), Proffitt, Pamela (ed.), "Ynes Mexia", Notable Women Scientists, Gale Group Inc., ISBN 0-7876-3900-1

- Yount, Lisa (1999), A Biographical Dictionary A to Z of Women in Science and Math, Facts on File Inc., ISBN 0-8160-3797-3

External links[edit]

- Mexía collection, 1918-1966 held by the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley

- Guide to the Ynés Mexía Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Works by or about Ynes Mexia at Internet Archive

- The Memory Palace Episode 107: Roots and Branches and Wind-Borne Seeds

- Oral history transcript of N. Floy Bracelin about Ynés Mexía, 1965 and 1967, via The Bancroft Library

- 1870 births

- 1938 deaths

- Mexican women botanists

- People from Washington, D.C.

- University of California, Berkeley alumni

- Deaths from lung cancer in California

- 20th-century Mexican women scientists

- American women botanists

- American people of Mexican descent

- 20th-century American botanists

- 20th-century Mexican scientists

- 20th-century American women scientists