It’s a warm June Sunday in Hamilton, Ontario, and a small strip of Roxborough Avenue is cordoned off. There are yellow bollards and diversion signs at either end. In the middle, blue fences mark out a rough oval shape, about 100ft long.

This is the city of Hamilton’s official street hockey rink – or, at least, the first stages of it. It was Sam Merulla’s idea, the city councillor who says he was inspired to “take back the street” after a group of kids in Hamilton were charged for illegally playing sports in the road.

“Street hockey is somewhat of a dying activity in our community,” Merulla says.

His solution is this rink. It’s not finished yet – there are plans to paint lines on the asphalt, and to add nets. But one thing the city has already been sure to do is put up two big signs on either side of the street, overlooking this spot: one states that physical violence or verbal abuse won’t be tolerated. The other, larger sign lays out the various restrictions. It lists the hours the site can be used for hockey (8am until dusk). It lists safety equipment (including a Canadian Standards Association-approved hockey helmet with protective face cage and “chin strap fastened”). And, most prominently of all, it lists 11 ball hockey rules.

In the cities of Canada street hockey (or road hockey, ball hockey, and hockey bottine in francophone Quebec) generally starts with a pile of hockey sticks in the middle of a residential road. Old ones, plastic ones, the ones nobody minds getting banged up a bit.

Someone brings a tennis ball, somebody else crushes a couple of Coke cans for goalposts. If you’re lucky, someone has an actual net – maybe even with netting still attached. Whether anyone is wearing anything approved by the CSA, particularly a helmet with chin strap fastened, is a non-issue. When cars appear, everybody simply moves out of the way to let them pass.

At least, this is how it used to be on Canadian streets. Walk the neighbourhoods of Halifax, Winnipeg or Richmond, and you might still happen upon the odd game, played mostly in the dying light of the short evenings. More likely, however, Canadian children will be elsewhere – tied up with after school activities, working on homework, or simply playing something else, safely indoors. No skinned knees, no rapped knuckles, no dirty hands.

It’s not just street hockey that’s disappearing from Canadian streets. It’s kids, too.

One reason played out last autumn on Esgore Drive, a wealthy but otherwise typical street in suburban north Toronto. Lined with multi-storey homes set back from the curb on grassy lots, Esgore Drive’s northern end winds up a few hundred metres from the Toronto Cricket, Skating and Curling Club. It is not the kind of street where you’d expect people to be charged with antisocial behaviour.

But Esgore Drive is precisely where a bylaw officer threatened to ticket a group of children for playing ball hockey.

This kind of thing happens all the time in Canada. In 2010, a 10-year-old and his friend were threatened with a ticket for playing hockey in the street in Calgary. In 2014, more than 500 people signed a petition against a Montreal-area bylaw after a father was fined for playing hockey outside with his son.

Most cities are reluctant to endorse street hockey. In Vancouver, you need a written permit. In Montreal it is mostly prohibited (except in alleyways). Ottawa allows it, but feels compelled to insist that “free flow of traffic is maintained once an adjustment in the game has been made to allow the passage of a car”. (For those of you who speak Canadian or have watched Wayne’s World, you’ll know that is the legal definition of yelling: “Car!”)

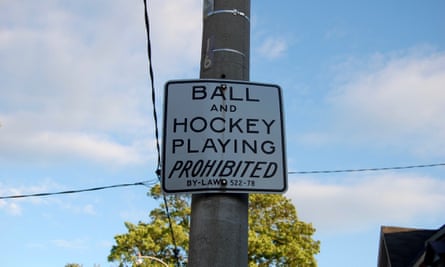

And in Toronto, arguably the nation’s biggest hockey market, the signs are explicit, even italicised for effect: Ball and hockey playing prohibited.

Even the people who defend the bylaws seem essentially baffled by them. They usually argue that the bylaws are only enforced if someone complains, and the city has done what it can to prevent injuries. But bylaws are, by nature, retroactive – they don’t stop accidents.

Regardless, according to Peter Gray, a psychologist and research professor at Boston College, there’s a much bigger problem: the very presence of a bylaw at all.

“Any laws that prohibit children from public spaces work against children’s capacities to play on their own and in their own ways,” Gray says.

Street hockey – unsupervised, improvised, free of adults – offers children something that almost nothing else does: ownership of space in the city.

Road sports are the de facto public space for under 18s. It is space that is, however briefly, controlled by children, and in which the rules are created and enforced by children.

And yet, though the idea that children should use the street as a common play area hasn’t disappeared completely, it has become bizarrely controversial. This is mostly due to the fact that parents are fed a consistent cocktail of worry – about lawsuits, about whether kids are getting into trouble, and about safety.

“There is a pernicious and completely wrong assumption these days that any time a child is not directly supervised by an adult, the child is automatically in danger,” says Lenore Skenazy, author of Free-Range Kids. “That’s why we get people calling 911 when they see a child walking to school or waiting at home alone or waiting in a car. It really is almost superstitious because it’s not borne out by reality … it’s a cultural delusion.”

Gray agrees and points to something else that has adults keeping kids out of the streets: the relatively new idea that children should do most of their development in school.

“School is taking up more of children’s time – there’s much more homework than there used to be,” Gray says. “Parents see themselves as assistant teachers. And they arrange for their kids to be taught even when they’re not in class. That leads to organised sports, where there’s a coach that’s teaching them.”

Despite its prominence as the nation’s most beloved pastime, organised hockey has developed a bad reputation for sucking all the fun out of the sport.

While junior ice hockey is full of salacious stories about parents turning team trips into parties, the more upsetting stories are the ones where they obsess about turning their children into star athletes: sending text messages to coaches marketing their seven-year-olds as top prospects, drilling their kids day and night, and even occasionally straying into physical and mental abuse. In 2013 Hockey Canada, the sport’s official body, and Bauer, a hockey equipment manufacturer, released the results of a study on why kids aren’t playing as much hockey. Among the reasons: “It wasn’t fun.”

“Society has forced us to always consider the worst case first and proceed as if it’s likely to happen: ‘How would you feel if your kid got hit by a car?’ ‘How would you feel if your kid doesn’t get a scholarship because he wasn’t practicing his hockey skills with a trained professional?’” Skenazy says. “Everything is framed that way and parents are scared to death. In response, they keep their kids in only supervised situations and … that’s not fun.”

But fun isn’t just about frittering away time. Because it is enjoyable, disorganised hockey – street hockey – teaches children skills they need to be successful adults, such as focus and concentration and repetition. “The kids have to work out: Was it in or out? What are we using as a goal? Was that cheating? If your kids can’t work that out, they can’t be leaders, they’ll be waiting for someone to work it out for them.”

It’s also how kids learn to socialise with each other in the urban environment. Goofing around, discovering interests, focusing on improvement, and overcoming the frustrations of communal living is what is positive about cities – but kids can’t learn to navigate it “if your mum is there, saying, ‘good shot’ or your dad is saying ‘no, try it this way,’ or the coach is saying, ‘that was out’,” notes Skenazy.

Hockey in general is not quite what it used to be for Canada’s kids. Youth enrolment has been overtaken by soccer, the new number one team sport for kids in the country. Hockey Canada has outreach programmes to attract the children of immigrant Canadians – but many tend to prefer basketball. The prohibitively high cost of hockey (an estimated C$3,700 per season for a child between 11 and 17) has made it a richer person’s sport: a Hockey Canada survey of 1,300 parents showed they had an average household income 15% higher than the national median, and noted: “The majority listed their occupation as a ‘professional, owner, executive or manager,’ a reflection of hockey’s new white-collar base.” But soccer and basketball are also more popular because of all the non-white faces who play. Hockey is a mostly white sport in a mostly multicultural country.

But hockey still matters to the national psyche. Three-quarters of Canadians in a 2013 poll by Statistics Canada still considered ice hockey to be “an important national symbol”. Indeed, it is engrained into the very fabric of the nation – it is a part of the story that we tell ourselves of being northern and free and not American. If we worry when the national teams fail to win, and whether National Hockey League teams will be sold to American buyers or moved to American cities, then we should be worried about street hockey, too. We should be worried that it is no longer a game our kids play, unprompted, unobstructed and unsupervised.

There are hopeful signs that we may at least deal with the suffocating bylaws. This spring, the city of Calgary removed a paragraph on its website stating that hockey nets were banned on streets, making it clear that street hockey is permitted. And this month Toronto’s public works committee started debating whether street hockey and basketball should be legalised again.

It is only the starting point to a solution. “Life brings life,” Jane Jacobs wrote of urban street activity. The more kids are in the streets, the more kids will be in the streets. When children are permitted to own their time and own their play, they will.

This is why, for all Merulla’s plans for Roxborough Avenue, Hamilton’s official street hockey rink won’t solve the real problem. It is a well-intentioned but ultimately wrongheaded cure, highlighted by the rules stamped on those signs. Street hockey’s illness is not a lack of streets, but a lack of kids free to fill them.

Is street hockey disappearing from Canadian towns and cities? Share your thoughts and memories on Twitter or in the comments below and tag your pictures with #GuardianCanada

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion