Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

A properly aligned Shoulderstand is a joyful thing, and props can make it possible.

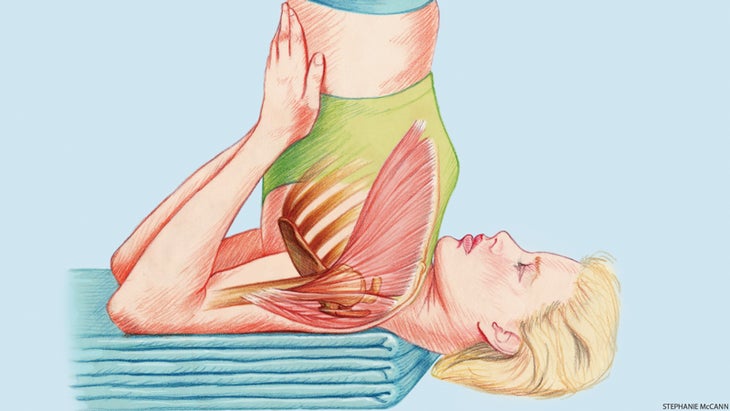

People who love Shoulderstand (Salamba Sarvangasana) really love it, and those who don’t, really despise it. The difference between loving and loathing the pose often depends on whether you can create a clean vertical line with your body and not bend, slump, or tilt. A stable, vertical Shoulderstand is easy, comfortable, and joyful, while a wobbly, crooked one is difficult, painful, and miserable. Several factors contribute to an ability to stand straight up in the pose, and one of the most important is grounding your arms firmly behind you while keeping your chest open. To attain this position, you need flexibility in two muscles: the pectoralis major and the anterior deltoid. Learning to lengthen them—or to compensate for a lack of length in them—can transform the agony of a misaligned Shoulderstand into the ecstasy of a pose that is upright and true.

How Things Stack Up

In order for your body to rise vertically from the floor in Shoulderstand, your skeleton must support you; that is, your bones must stack neatly so they bear most of your weight. With this alignment, the only work your muscles have to do is to contract once in a while to correct the position of your bones when they drift out of line. When your body is lined up this way, you can breathe more easily because your belly and chest are open and the muscles surrounding them are relaxed enough to allow free movement. In other words, when you’re able to create proper skeletal support, the posture will require minimal muscular effort and your breath will flow easily, which will allow you to rest in the pose for a long time without fatigue. Staying in the posture gives it time to work its physiological magic. The prolonged stretch on the neck and upper shoulder muscles relaxes them, interrupting the vicious cycle of nerve activity that keeps them tense, while the inverted posture stimulates blood pressure sensors in the neck and upper chest, triggering reflexes that calm the brain, slow the heart, and relax the blood vessels.

In a poorly aligned pose, the shoulder blades, spine, pelvis, and legs don’t line up vertically. When they don’t rest squarely on each other, their weight tends to make the whole body fold at the joints: The hip joints tend to flex, so the legs fall forward and the pelvis hangs back, and the spine tends to round, making the chest cave in. To pull your body up against gravity, you have to tighten several large muscles very forcefully, especially the erector spinae of the back and the posterior deltoids of the shoulders. When your alignment is out of whack, these muscles don’t just contract intermittently, as they do to correct bone alignment in a vertical pose; instead, you have to hold them constantly tense against the force of gravity to prevent your body from crumpling to the floor. Despite your best efforts, your trunk usually remains partly collapsed in front, so it’s hard to breathe.

Furthermore, if you try to straighten up without sufficient chest and shoulder flexibility, your arms may lift off the floor. Your body then wavers, so you have to make frequent postural corrections by sharply contracting your already tense back muscles. The combination of tense muscles, difficult breathing, and constant vigilance causes rapid fatigue and, oftentimes, sharp pain in the back or elsewhere.

Flexing and Extending

We’re focusing mainly on the arms, chest, and shoulders here, but it’s essential to mention that the ability to align your body vertically in Shoulderstand depends partly on how far you can flex your neck. If you can’t flex your neck very far, you can compensate by elevating your shoulders on a stack of blankets and resting your head at a lower level. Then, your neck won’t have to bend so far forward to get your body to the upright position, and your ability to stand straight will depend on how far you can extend your shoulders.

To understand what shoulder extension is, stand up, interlace your fingers behind your back, then lift your arms and chest upward while rolling the tops of your shoulder blades backward and down. This action of moving the arms behind you and up is shoulder extension. The higher you can lift your arms without collapsing your chest or shoulders, the greater your extension and the greater chance you have of getting a nice vertical lift in Shoulderstand. If you have sufficient range of motion and you do this same set of actions while upside down in Shoulderstand by pressing the backs of your arms firmly into the ground behind you, it will place your body weight squarely on top of your shoulders and impel your chest forward toward the open, upright position. To arrive at a vertical Shoulderstand, your chest and shoulders must be flexible enough to allow your chest to reach the upright position while your elbows and the backs of your arms push strongly into the ground directly behind the shoulders.

Once you reach this milestone, you’re in position to bend your elbows and place the palms of your hands on the back of your rib cage. This allows you to rest the weight of your trunk on your hands, which transmits the load through your forearms and elbows to the ground. If you move your hands close enough to your shoulders, you wedge your forearm bones between the back of your rib cage and the ground, providing buttresslike support to the upper back and chest. This takes a load off the back and shoulder muscles, while stabilizing the vertical line of your skeleton by linking it solidly to the floor. This action is one of the keys to an easy, relaxed Shoulderstand.

To get your arms into this position, you need flexibility in the pectoralis major muscle and the front (anterior) part of the deltoid muscle. The pectoralis major connects the front of your upper arm to your collarbone (clavicle) and to the front of your chest (the sternum, rib cartilages, and upper abdominal connective tissue). When your left and right pectoralis major muscles contract simultaneously, they pull your arms forward (flexion), pull them together in front of you (adduction), and rotate them toward one another (internal rotation). If these muscles are tight, you won’t be able to fully extend your arms behind you in Shoulderstand. Either your elbows will lift off the floor as your chest moves forward, or your chest will collapse as your elbows reach down to the floor. Meanwhile, the frontal adducting and internally rotating actions of the “pecs” will pull your elbows wide apart in back, moving the arms to a position where they can’t support your trunk from behind.

The anterior part of your deltoid muscle connects your upper outer arm to the outer part of your clavicle, near where your clavicle connects to your upper shoulder blade. When the front of your deltoid contracts, it lifts your arm in front of you (shoulder flexion), so if it’s tight, it limits your ability to reach your arm behind you (shoulder extension). In Shoulderstand, tight anterior deltoid muscles will prevent your elbows from reaching the floor, or, if you take your elbows all the way down to the floor, the tops of your shoulders will slump forward toward your chest.

The bottom line is that tight pecs and frontal deltoids will lift your elbows up away from the floor and apart when your body is aligned in Shoulderstand, causing a cornucopia of trouble. The obvious solution is to gradually stretch these muscles so that your upper arms can eventually reach the floor directly behind you in the pose. In the meantime, you can use props, both to help the stretching process along and to make the Shoulderstand not just bearable but actually enjoyable.

To hold your upper arms closer together, you can practice with a belt looped around them just above the elbows (if the belt makes your arms fall asleep, you should loosen it or take it off). To ground your upper arms, use a wedge-shaped prop or a firm, folded sticky mat underneath your elbows.

Put It Together

Here’s how a person with tight pectoralis major and anterior deltoid muscles can use props to mobilize the shoulders and create a more grounded, lifted, and satisfying Shoulderstand. Fold four yoga blankets as follows: First, fold a blanket in half by joining its two short ends, then fold the resulting rectangle in half again by joining the two short ends, and finally, fold the last rectangle in half by joining the two short ends. Each blanket should now have one long folded edge. Stack the four blankets neatly with their long folded edges one atop the other. Place the stack about 8 to 10 inches away from a wall, with the folded edges facing away from the wall.

If you have a wedge-shaped prop that’s long enough to support both of your elbows, place it on the blankets on the side nearest the wall. The high side of the wedge should face the wall. If you don’t have a wedge, fold a sticky mat end to end, then fold it in the same direction two more times to create a long, narrow rectangle. Place the rectangle atop the blankets parallel to the wall and on the side of the stack that’s nearest the wall. Now take a yoga belt and make a loop that’s as wide as your shoulders (wider if your shoulders are very tight).

Holding the looped belt in one hand, lie down on the blankets with your legs up the wall, your shoulders about two inches away from the folded edge, and your head on the floor. Bend your knees, press your feet into the wall, and lift your hips.

Loop the belt around your upper arms just above the elbow. Turn your palms up, and hook your little fingers around each other (if you can’t figure out how to do this, or if your elbows hyperextend, interlace all your fingers instead). Straighten your elbows, rotate your upper arms outward, press the backs of your upper arms into the wedge or sticky mat, move your hips farther from the wall, and move your chest gently away from the wall. Shifting your weight slightly and carefully from side to side, roll the tops of your shoulders back toward the wall, so you end up standing directly on the tops of the shoulders. Be careful not to strain your neck by forcing your shoulders to move too far too fast; if you can’t get them all the way underneath you at first, just go partway. Only the base of your neck should remain on the blankets; the rest should extend beyond the edge.

Release your interlocked fingers, bend your elbows, and place your hands on your back (it’s crucial that your hands not slide on your back, so, if possible, slip them under your shirt so they touch bare skin for added friction). Walk your hands along your back as close to your shoulders as you can get them; then, without allowing your hands to slide, flatten your palms on your back and press it forward.

Now, if you feel ready, cautiously take your feet away from the wall. Engage the leg muscles to the bones strongly to create more vertical stability. Be very careful not to lose your balance and fall. Try to create a straight line from your shoulders through your hip joints to your ankle joints. Make that line vertical by tilting your whole body to the point where you feel a sense of lightness and your lower back muscles and abdominal muscles relax at the same time. Gaze quietly toward your chest and enjoy your new Shoulderstand. Stay as long as you are comfortable. To come down, remove the belt first, then slowly lower your hips to the floor.

Roger Cole, PhD, is a certified Iyengar Yoga teacher and sleep research scientist in Del Mar, California. For more information, visit rogercoleyoga.com.