- India

- International

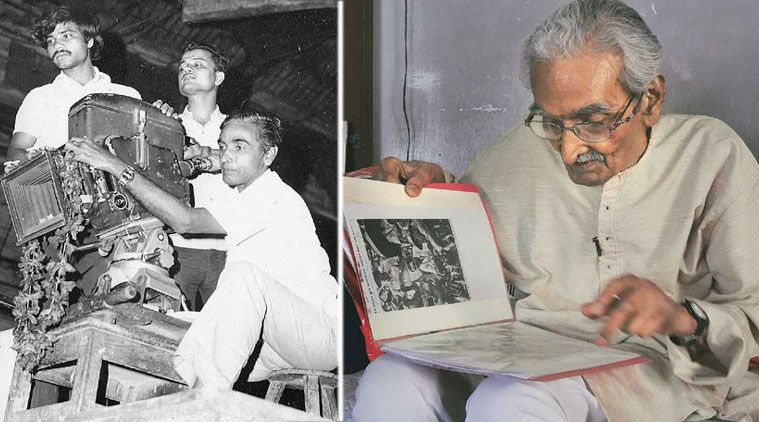

Ramanand Sengupta: Life Through a Lens

Ramanand Sengupta, a renowned cinematographer in Bengali cinema turns 100 and looks back at a career studded with great films.

Ramanand Sengupta, a renowned cinematographer in Bengali cinema turns 100 and looks back at a career studded with great films.

Ramanand Sengupta, a renowned cinematographer in Bengali cinema turns 100 and looks back at a career studded with great films.

The year was 1948. The south Kolkata neighbourhood of Tollygunj, then the filmmaking hub of India, was limping back to normalcy after a lean phase during WWII. It was a strange, damaged city, full of Bangladeshi refugees, that welcomed French auteur Jean Renoir that year, but he was in for many surprises.

The first amongst them was the immaculately dressed spot boy who helped him audition child actors for The River (Le Fleuve, released in 1951), the film he had come to shoot in Kolkata. Ramanand Sengupta was already an established cinematographer when he volunteered to be a clapper-boy for the iconic film. “He wanted to learn from the experience. He had no ambitions of helming the camera for Renoir. He just wanted to observe,” says Siddhartha Maity, who is writing a book on the the only Indian cinematographer to have worked with legends like Jean Renoir, Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen. He is also making a documentary on Sengupta titled, Alor Frame e Chhayar Saaj (Framing Light Against the Shadows).

Renoir, however, observed a spark in his “quick-witted” clapper boy. “In his memoir, Renoir mentioned that he noticed how the clapper boy would follow instructions before even the light men could. He knew exactly what the director wanted,” says Maity. Eventually, Renoir decided that Sengupta deserved something more. “Since The River was the first technicolor film ever made, Jean Renoir sent his nephew, Claude Renoir, and Sengupta to London to specially train in this new technology,” says Maity. For the boy from Shantiniketan, who could not afford an engineering degree, this was no less than a dream come true.“I completed my matriculation and went to a technical school. We didn’t have the money to afford an engineering degree. My technician’s degree helped me get a job in the film industry in Madras. Later, I shifted to Kolkata,” says Sengupta, seated in his south Kolkata apartment which he shares with his son and his family.

Last month, Tollywood veterans such as National Award-winning director Goutam Ghose, Satyajit Ray’s favourite cinematographer Soumendu Roy and actor Sabyasachi Chakraborty and many others came together to honour Sengupta on his 100th birthday. Dapper in a crisp cotton kurta and dhoti, Sengupta sat ramrod straight on a chair. He is all angles and lines, but a childlike smile fluttered around his lips and he was in a mood to relive a lifetime spent in the Bengali film industry.

When he returned from London, Renoir decided that Sengupta would get behind the camera for the film along with Claude. Renoir was so impressed with Sengupta’s work that he chose him to shoot a documentary on Bhubaneshwar and Chandigarh as well. “He was really friendly with my family, too. At a party at the Great Eastern Hotel, the executive producer of The River danced with my wife Minu. They were very graceful together, but Renoir didn’t seem very happy about it. After the party, he invited my wife and me to his room and warned us against ‘white’ men who apparently are experts in seducing women,” guffaws Sengupta.

Meanwhile, everyone in the city wanted a piece of the French filmmaker. “Though this is a very crude parallel, it might drive the point home. Imagine Steven Spielberg coming to Kolkata now and deciding to spend a year here to make a film on the city. Renoir’s visit generated that kind of a buzz,” says Maity.

But the auteur’s visit also changed the landscape of Indian cinema, mainly because of his intimate interactions with a young man in his 20s, Satyajit Ray, who was then pursuing a career in advertising. “Ray would spend hours with Renoir every day.When I was chosen for the job, Ray sat me down and told me all about Renoir and his incredible legacy. He told me about his father, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the great Impressionist painter. I knew nothing about Impressionism before that,” says Sengupta.

Five years later, Ray made Pather Panchali, which gave birth to a new language in Indian cinema. Meanwhile, Sengupta, who now had earned the sobriquet of being the saheb-trained cinematographer, quietly changed the idiom of Bengali cinema, too. “After The River, I worked with Ritwik Ghatak on his debut film Nagarik. He would keep asking me what Renoir said. One day, I told him that the saheb was deeply affected by the Partition and the problems faced by millions of refugees who had to come to Kolkata overnight. Renoir had mentioned how he would have made films only on that topic if he were from India,” says Sengupta. Ghatak, too, kept coming back to that very theme in his illustrious career.

In a career spanning more than four decades, Sengupta has been associated with many landmark Bengali films such as Shilpi (1956), Nishithe (1961), Headmaster (1959) , Teen Bhubaner Pare (1969)and Raat Bhor (1955). “He brought a certain kind of refinement to Bengali cinema. Before him, Bengali films were mostly shot in the flat Hollywood technique. He used to play around with darkness, give some depth to each frame,” says Maity.

This was the time when exciting new things were happening in the Bengali film industry. Ray was garnering world attention, Ghatak and Mrinal Sen were also redefining the boundaries of conventional filmmaking. Sengupta was right in the middle of all these. “Both Ghatak and Sen made their earlier films with him. Utpal Dutta, who is better known as an actor, made Megh, a noir film with Sengupta in 1961,” says Maity.

Sengupta was also the founding member of Kolkata’s iconic Technicians’ Studio (founded in 1952), a one-of-its-kind studio run by technicians. “The best thing about the studio is that it ensured that the technicians were not short-changed. They provided technical assistance to all of Ray, Ghatak and Sen films. All his life, Sengupta fought for the rights of his fellow technicians. To promote the studio, he worked for free for decades. He let go of important foreign offers to ensure that Technicians’ Studio flourished,” says Maity. But that also meant that Sengupta and his ilk had to make do with very little infrastructure. “Producers would hire our studio as a package. But we had very limited equipment. We didn’t even have photometers to gauge light or multiple cameras. But we improvised by taking long, exhausting tracking shots,” says Sengupta.

Sengupta also has the reputation of being one of the most straight-talking men in the industry, which meant that he managed to rub many stalwarts the wrong way. According to Tollywood lore, he managed to offend matinee superstar, Uttam Kumar with his bluntness in the 1960s, when the latter was the reigning deity of the Bengali film industry.

“It was such a long time ago. We were working in a film together. He had walked into the set and made fun of the lighting in a very lighthearted manner. I was young then and lost my cool easily. I retorted sarcastically by saying that he seemed to know a lot about lighting himself. However, he had the grace to let bygones be bygones and even took my son in one of his films,” says Sengupta.

Photos

Must Read

Apr 27: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05