Seven years ago, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg famously leaned into the mic at a Harvard Business School event and urged her audience of future MBAs to bring your "whole self" to work—the idea being that genuine interactions on the job make us more invested in our colleagues and therefore the work we do.

The message spread like a LOLcat video, and since then, financial institutions and tech firms alike have touted their embrace of authenticity, urging current and future employees to get — and stay — real on the job. The new "come one, come all" script for job listings (this one for a Walmart cybersecurity manager): "We welcome all types of talent where your story is included and you bring your whole self to work!"

So what exactly constitutes authenticity on the job? "In my case, it might look like this: I would really like to raise my hand in a meeting because I have something to say, and coming from me, a black Christian academic woman, it might be divergent from the other opinions being shared," explains Tina Opie, Ph.D., an associate professor in the management division at Babson College. "But I do it anyway. It's what I want to do internally, and it's concordant with my external behavior."

Toon Taris, Ph.D., a professor of work and organizational psychology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, uses three metrics to evaluate whether employees feel authentic: "You're able to engage in activities and behaviors that you personally find important and meaningful. You feel that your work fits well with your personal values, interests, and convictions — you don't have to hide how you really feel. And you don't need to put much effort into behaving the way others expect you to behave."

Creating a workplace where employees ace Taris's test can be profitable for everyone involved. "We've found that people who are authentic at work are considerably happier, more satisfied, and less stressed," he says. And happy workers get more done: Researchers have found that even a temporary boost in mood can increase productivity by around 12 percent. People who feel authentic in their workplaces are also more intrinsically motivated to do their jobs, which can help bosses, too — there's less need to micromanage.

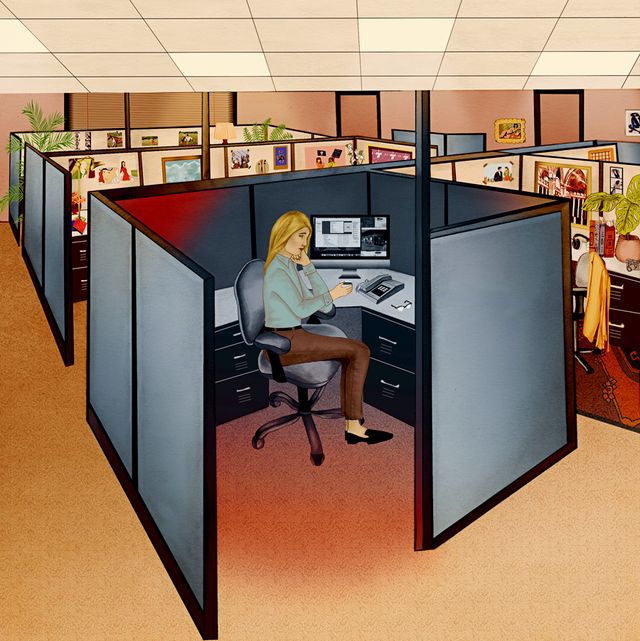

Sounds great, right? But there's just one problem: Being yourself at work isn't always easy, and suppressing part of one's identity can give rise to serious issues. According to Taris's research, it's correlated with boredom and burnout; it's also been found to increase perceptions of colleague discrimination, which can lead to lower job satisfaction and thoughts of quitting.

Opie puts it this way: "Think of aspects of your identity as buckets. Say I have a 'woman' bucket that's full to the brim — a huge part of my sense of self is about being female, and I seek out opportunities to express myself in that way. Yet in my workplace, I receive constant feedback that women are not valued, so I feel the need to alter how I behave and how I present myself. I find myself carrying this heavy 'woman' bucket and trying to hide it at the same time."

Such circumstances can create a powerful sense of cognitive dissonance — in this case, the psychological discomfort that comes with having one value while being rewarded for acting in opposition to it — that is compounded over time. The hiding can lead to shame, Opie says. "You become upset with yourself because you think you're not proud or courageous enough to stand up to people who are devaluing a key part of your identity." The longer this goes on, and the more essential the part of yourself you feel forced to deny, the more your mental health can suffer.

Adamaris Mendoza, 44, started her career in the male-dominated finance industry. "For a Latina black woman, it's rare to get the job in the first place. So once you do, you feel like everyone is watching you." And according to Mendoza, they didn't like what they saw: Colleagues told her that aspects of her personality weren't a good fit for the field. "I'm very expressive. I use my hands when I speak, and my voice is not exactly on the quiet side," she says. "I'm pretty sure this is why I was often told in performance reviews that I came across as aggressive at work."

So when Mendoza was around her coworkers, she tried to stifle these personality traits and become more "corporate." She remembered the way her father, who had emigrated from the Dominican Republic and worked as an executive at Fortune 500 companies, would put on his work clothes every morning and, in her eyes, become another person. "I started doing the same thing," she says. "I covered up my real self in order to fit in." She splurged on designer clothes, shoes, and bags — not because she liked them but because to her they represented the costume of the modern businesswoman. It wasn't until she undressed at night that she felt like herself again.

After a few months of this performance, Mendoza was finding it increasingly difficult to reconnect with her real self. She felt that she had to put up a front — successful, satisfied — even around her friends. "Hiding your personality at work takes a lot of mental and emotional energy," says Melody Wilding, a licensed social worker and career coach who specializes in the issues ambitious women tend to face. "It leads to disengagement from everything." Mendoza began getting migraines; she stopped socializing and developed digestive problems. It got to the point where she was having so much trouble taking care of herself that she moved in with her parents.

"In our research, we've talked to a lot of employees who feel like they're concealing a 'stigma,' and in many of those cases we've seen that there's a real cost to hiding," says Mikki Hebl, Ph.D., a management professor and the Martha and Henry Malcolm Lovett Chair of psychology at Rice University. Some people who feel they are inauthentic versions of themselves have reported feeling pigeon-holed, deceptive, and immoral. They can become emotionally exhausted and more reactive to stressors. One study found that the more difficult it was for people to be real in their jobs, the more depressed they were; a separate study found depressed individuals tend to have "work performance impairment."

As one of very few black students in her doctoral program, LaTonya Summers, Ph.D., was acutely aware of the negative stereotypes that might be lurking in the minds of her professors and peers, so she took care to be on her best behavior. "I didn't always speak up," she says. "There were times when I didn't share how I felt about certain things for fear of backlash or being perceived as an 'angry black woman.' " Summers, now an assistant professor of clinical mental health at Jacksonville University in Florida, worked hard to tread lightly and blend in. "I equated success with whiteness," she says. "White professors took me under their wing, and I'm so grateful for that, but I started to think and act like them" — conforming to what she saw as "the white standard" by dressing, talking, and expressing herself in a way that felt "not black." And it worked: She shot up through the ranks of academia. In the process, she says, "I lost my racial identity."

Summers found herself profoundly conflicted: Who was she anyway? This cognitive dissonance is a "double whammy," Opie says. "You'd like to be your authentic self, but if your audience has a positive reaction to whatever you've tried to change about your identity, that feels like a rejection of your authentic self." Then Summers encountered blatant racism, most notably from an older, white, female professor, and that sent her into a depressive spiral.

Even when the effects of inauthenticity aren't dire, they still aren't conducive to doing great work — or feeling good about yourself. Negative repercussions can include intrusive thoughts, distress, distractibility, and, in some cases, memory impairment. Even when you may appear to be maintaining relationships and interacting with ease, Hebl says, you may be missing out on genuine social support and the benefits of true friendship.

Katie Kim, 29, discovered that compartmentalizing her personal and professional life proved much more difficult than she expected. When she came out to her family as a lesbian, it didn't go very well. So after college, when she started as an analyst at the consulting firm Accenture, she decided to get back in the closet. "I thought, if the people who love me the most in the entire world have a hard time accepting me, what can I expect from strangers?" she says. Besides, she didn't think her romantic life had any relevance to her job: She just wanted to put her head down and work hard.

As Kim's career blossomed and her role evolved to include more face time with coworkers, she became increasingly uncomfortable with the fact that she hadn't told anyone on her team about her sexual orientation. "It was starting to get weird," she says. Conversations about weekend plans, for example, felt awkward. "You can only talk about things in general terms. Like, 'Oh, I went out with my cousin...' and then the conversation dies. Not being able to speak freely for fear of outing yourself might not seem intense in each moment, but over time it made me feel sad and isolated."

Bringing just your half-self to work can also take a toll on the rest of you. At her previous job, Peri (who asked that only her first name be used), 26, worried so intensely about colleagues not understanding her religious convictions that she found herself flailing. Peri is a human resources specialist and Orthodox Jew who, four years ago, decided to follow strict observances including abstaining from physical contact with members of the opposite sex. Though she might vaguely mention being "religious," she refrained from saying anything about her religious practice.

The absence of information put Peri in some uncomfortable situations. The people in her department were physically expressive: lots of handshakes and high-fives. "I eventually decided I would be OK with these gestures if the other person initiated them," she says, even if that person was male. Then she began to worry that not initiating professional handshakes might cause people to take her less seriously, so she started being the one to extend her hand first. Embraces were more complicated. Peri mediated a lot of intense conflicts, and it was customary for colleagues to "hug it out" afterward.

She tried to literally sidestep the issue, offering a sort of one-handed pat, but even this, of course, was physical contact, and ultimately she felt like she was betraying her faith. These everyday interactions made Peri extremely anxious; her ears would turn red, she'd itch all over, and she'd become solemn and quiet. "People would ask me what was going on, and I'd tell them I was fine — but I wasn't," she says. The irony, Opie points out, is that Peri's desire to protect her privacy may have had the unintended effect of piquing curiosity. Perhaps if there were more visible symbols of her religion, or if coworkers better understood her beliefs, they wouldn't have kept pushing her.

Sometimes the best way to come clean about who you are is to change jobs — and find a fit that feels right from the start. Last year, when Peri interviewed for a new position (in a department of mostly women), she decided to tell her potential employers up front that her religious obligations prohibited her from working on Jewish High Holidays — essentially outing herself as an observant Jew.

She was nervous, she says, but "I realized I didn't want to go through my career feeling like I couldn’t share who I really am." To her delight, her new employer accepted these terms — and made Peri feel accepted, as well. "I'm not embarrassed by sharing my practices," she says. "I see now that if I could have been open and honest with the people at my old job, I could have saved myself a lot of pain."

Katie Kim didn't want to change jobs; she wanted to change how coworkers saw and understood her — the trick was figuring out how to do that. While some people at work knew she was a lesbian, others who she interacted with daily still had no idea. "I felt like something needed to happen," she says, "but I wasn't sure what to do." She decided to open up to a senior product leader at her company, an openly gay man.

At a happy hour for LGBT employees, she pulled him aside and confided that she was having a hard time. "I asked him, 'How do you know it's OK to be out at work when it's not related at all to our ability to do our jobs?' He said, 'Katie, it is related. You have to be authentic to yourself in order to be your best for your clients.' " He advised Kim to come out casually rather than making a big announcement. A few weeks later, she tried to play it cool as she dropped the word girlfriend into a conversation with clients. "After that I felt so, so free," she says.

LaTonya Summers had to be her own role model. Because of her mental health education and training, she was fortunately able to recognize what was happening to her ("The crying, fatigue, self-doubt, repressed anger, and depressive symptoms were clear"), and she sought treatment. After she finished her Ph.D. program, she started a mentoring group at Jacksonville for female students of color. Says Summers, now 46, "It's important to me that other young women are able to find their voices and use them sooner than I did."

Therapy helped Adamaris Mendoza, too, get through the worst period of her life and understand that she needed to make a change. It also had a surprise bonus. When she eventually left finance, her therapist recommended Christian counseling courses, and Mendoza fell in love with the process. "I was so inspired by my own progress that I wanted to help other women," she explains.

She trained to become a therapist, and then three years ago, more than a decade after leaving finance, she became a life coach. "I could just show up as myself: I felt like I could laugh or cry and be caring toward others. And those things attract new business! Clients often tell me they knew they had to work with me after watching one of my videos or meeting me in person," Mendoza says. "Now I tell them what it took me so long to learn: Being yourself might feel risky, but it's so worth it."

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY