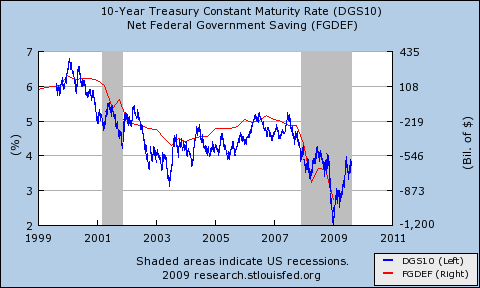

Brad DeLong has been writing about the falsity of the claim that large-scale government borrowing in a liquidity trap will lead to soaring interest rates. I was looking for some corroborating data, and came up with a picture that surprised me, though it shouldn’t have. Here it is:

Net federal saving is, roughly, the budget surplus (so it’s negative if there’s a deficit.) It turns out that there’s a strong correlation between budget deficits and interest rates — namely, when deficits are high, interest rates are low.

On reflection, it’s obvious why: a weak economy both drives up deficits and drives down the demand for funds, while a strong economy does the reverse. Thus the surpluses of the late Clinton years were associated with high interest rates, while the current recession has depressed both rates and revenues.

And what about the bounce in interest rates over the past few months? It reflects a gradual reduction in the end-of-the-world discount: interest rates have risen along with stock prices as investors have gradually become convinced that we’re avoiding a second Great Depression.

Overall, Brad’s point is exactly right: the US government is borrowing huge sums, but interest rates remain low by historical standards — which is exactly what you’d expect given what we learned from John Hicks, 72 years ago.

Comments are no longer being accepted.