interviews

A Fantasy Novel That Forces Us to Face Reality

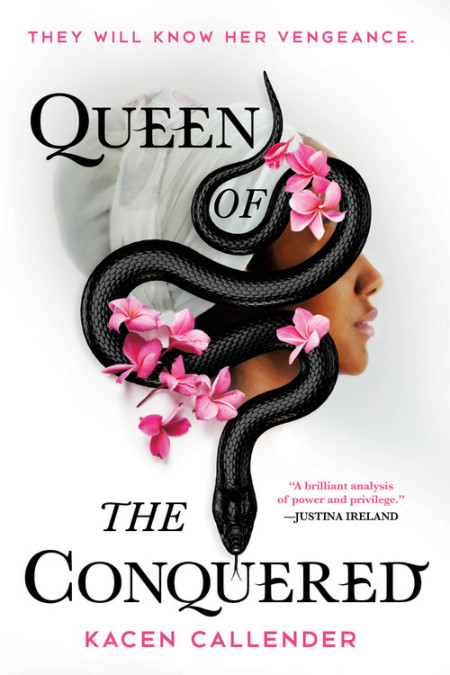

Kacen Callender’s "Queen of the Conquered" faces issues of oppression, privilege, and complicity head on

The beautiful cover of Kacen Callender’s new book Queen of the Conquered may belie the harshness of the world depicted within. There’s slavery, beheadings, colonialism—-all in the first chapter alone. The suspense Callender captures encourages introspection into the world we live in now along with the colonialist practices that continue to pervade so many nations, especially areas inhabited by people of African heritage. The fictional/not-quite-fictional world is based on Callender’s childhood home in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

We’re introduced to Sigourney Rose, the last of her family after a brutal massacre by the colonizers who planned the erasure of her whole family. Since that fateful day in her childhood, vengeance has been on her mind, and she sees her chance in a calculated marriage, an invitation from the King to meet with other royals during Storm Season, and her own kraft—the ability to enter and manipulate people’s minds. What unravels is when the hunter becomes the hunted and bodies pile up. Who will be given the throne? Who is killing those in Sigourney’s way? And how will this all end, especially when Sigourney may not be any better than the elite she seeks to overthrow?

I spoke to Kacen about how the fantastical meets our contemporary society, what themes were prevalent in this novel, and how we as readers and people should recognize privilege in the relationships we hold and the ways we see the world. Kacen Callender’s previous books include award-winning middle grade and young adult novels. And 2020 will see a sequel to Queen of the Conquered, King of the Rising. (This interview was edited and condensed. You can hear the full interview on the Minorities in Publishing podcast.)

Jennifer Baker: You’re switching gears big time for Queen of the Conquered. How do you go about the difference in execution, and who you were thinking about as the end reader when writing for younger and older audiences?

Kacen Callender: The difference for me for all the different age ranges comes down to the hope that’s at the end of the book. For the younger audiences, I personally feel it’s important that the reader understands there’s still hope in this world. I feel like at that age, especially because I struggled so much with depression and mental health when I was younger, I felt like there was absolutely no hope. And if I found books at that age that kind of solidified that thinking, I don’t know if I would still be here. I really needed books that suggested that, “Yeah, things are tough right now, but you will make it through.” For the adult age ranges, I hope that at this point we have lived long enough to see that there are dark times, but there is still hope for things to change, that even if it’s a cycle at this point, things can still get better. So I feel more comfortable with the ending that is just brutal and doesn’t necessarily suggest that things will be perfect for the characters in the story. YA is also kind of in the center of that, where there can be a good mix, whereas I want the middle grade to be as hopeful as possible. YA can be realistically hopeful, not completely devastating at the end, for my taste, for my personal writing. The adult books can be absolutely no hope at all for any of the characters.

JB: When we come to Sigourney, do you feel like she’s hopeful? She has a singular mission, and it seems that’s what drives her. I know she’s your character, so maybe it’s a little unfair. But that hope you were talking about: is that within her, not so much the book itself?

I wanted to take a look at the way that discrimination and oppression interact when you see yourself have privilege.

KC: She’s a very morally gray character. You hear the description [of her], and you may think, “Oh, yeah, she’s a freedom fighter. Of course I’m going to be on her side.” I wanted to take a look at Sigourney through the lens of her privilege because I think that’s an aspect we don’t always look at—even as an oppressed person, I also have my privileges. Another aspect of that is: When I was in St. Thomas, the U.S. Virgin Islands, I was privileged enough to be sent to private school. But even then, I was still the only Black person in the room, and I was bullied and discriminated for years. Then I came to the States, and I went to basically another almost all-white college, again had the privilege to attend a very expensive school, but was still discriminated against as the only Black person in the room. And then I went to New York, and it was kind of this running theme in my life. I was in publishing, and I had the privilege to be able to afford to live in such an expensive city, or even to make it into the room in publishing, but I was the only Black person there for years. So I wanted to take a look at the way that discrimination and oppression interact when you see yourself have privilege. A lot of Sigourney’s struggle with that was inspired by my own struggles with being a person of privilege but also oppressed. So the question of hope for Sigourney comes in with whether or not she can be redeemed. She’s such a morally grey character that she herself looks down on her own people. She herself is a slave owner. Even as she’s trying to free her people, she also owns slaves, and that’s something I was inspired by years and years ago when I first heard that Black people had owned slaves historically. I was a teenager. I was blown over. The question remains after all these years: “How could you do that to your own people?” Ultimately the question of hope is rooted in whether she herself can be redeemed as a morally gray character, whether she can redeem herself and all the mistakes that’s she’s making throughout the story.

JB: It made me think about Obama, too. I remember the 2008 election, and the theme was, like you said, hope. “Change is coming.” Their tagline was: Yes, we can. I could only imagine what it’s like for someone like Obama to be the first, be the only, and then get into the space, and to really come in with those “radical ideas,” and suddenly realize the power structure is so embedded in ableism, white supremacy, homophobia, transphobia. And that all made me think of Sigourney because I’m gonna admit I thought, “Girl, are you serious right now? Do you really think that once you get in there that things are gonna change?”

KC: I’m happy you said that because that is a big question throughout the book: Whether she realizes that she will really be able to change the system, or whether she’s actually a part of that system. Even as she tells herself she wants to destroy it and she wants to overcome the system of privilege and oppression by being the top person. Is she actually changing that or is she becoming a part of it by joining that system that she is the Queen of the islands?

JB: The added effect of giving her the ability to see what people think of her consistently, the pain of that and the stress of that and the appearance of strength and fortitude for her, which is just especially – she is a Black woman and a Black woman’s burden of you don’t get to be this. And then you’re in the room, and you’re the target, and she’s always dealing with it. So I’m wondering also, as creator, how did you approach it?

KC: For the morally gray aspect of things, I went in wanting to write a realistic character, first and foremost. I think it’s difficult for all of us to look at our own privilege and look at how we are also hoping the system that we’re in—we don’t really want to look at that. We don’t really want to look at how all the technology that we’re on is destroying people’s own freedoms as they’re forced to work. Or even corporations, like Amazon…

JB: Facebook.

We’re in the system of oppression, and we are going along with it rather than burning it down.

KC: It’s difficult for us to take a look at the fact that we are in a society where we are trying to get our own privileges and our own comforts and we are hoping this system of oppression justifies us existing in it. I wanted to look at Sigourney’s character as a symbol for all of us. We are Sigourney. As ridiculous as that sounds, each of us are making the same mistakes that Sigourney is making by being a part of the system. That’s ultimately what I went out to do. I wanted to take a look at the fact that we’re all morally grey and all of our choices—the fact that we’re part of the system means we’re making the same mistakes as Sigourney. I personally look at the story and think, “I hope to God I would never have to do the same things that Sigourney would do.” But it’s also so difficult to know if we were Black people with the privilege to own slaves, would we have? I really hope to God no. At the same time, we’re also doing the same thing right now where we’re in the system of oppression, and we are going along with it rather than burning it down basically.

JB: I feel like the magic helps enhance it because then Sigourney has the ability to hear people’s thoughts. Was that always part of the plot? Because I think with or without it, it still would have played out similarly to how you thought.

KC: The magical element was really important from the beginning because it was also a symbol of the ways that society has decided who is allowed to have the power. The “kraft” is actually a Danish word that literally means power, so there are some times where I have a little bit of fun with the word choice. I’ll say who gets to have the “kraft,” and I’m literally asking who gets to have the power. From the beginning, it said that the royals, that the Fjern, as they’re called—the colonizers, the oppressors—they will execute anyone who has the power, who is an islander. That’s their way of literally taking power from the islanders and saying they’re not allowed to have this ability that can further you. That’s just a metaphor for society right now. Who is allowed to have the power to go to school, to have the jobs for themselves in this society? There are people who are being oppressed in that same way.

With Sigourney’s power, it was particularly important to me for her to be able to read minds and control bodies because I used to identify as a Black woman. I’m trans. I’m nonbinary even. As a nonbinary person who is also Black, I feel like we can always kind of sense what a white person is thinking. I feel like we can always sense how we are being viewed in society as we walk down the street, and we can feel the white gaze looking at us. The way Sigourney constantly sees the white people looking at her as well as judging her for skin tone and not seeing the power that can be in her, and thinking that the way that she looks and her race equals a monstrosity because of the way that we’ve been brainwashed in this society to view Black people. I wanted her to be able to look at the racism in a way that I feel like I can see it very clearly whenever I’m walking down the street or whenever I’m the only Black person in the room.

JB: So they are Dutch?

KC: Yeah, they’re Danish. It’s based on the U.S. Virgin Islands. Historically we were owned by the Danish before we were sold to the United States. So a lot of the words, a lot of the island names, the street names, and the names of the manors, were taken from street names and island names that are in the Virgin Islands.

JB: It seems like so much of your writing is also very much embedded in the Virgin Islands, in the Caribbean, and all that stuff, which is so nice to see, but I also think it lends being born and raised stateside in New York City. it adds such a level of poetry and a dynamic-ness to your work, which is what I just loved about your writing in general. I’m interested in what were you reading and all that stuff to kind of cater to and develop your voice.

I should’ve been reading Toni Morrison in high school, not Shakespeare.

KC: As a child, because I did go to private school, I had a lot of teachers that were basically all from the States. I did feel like I got an education that was very white.

JB: Really?

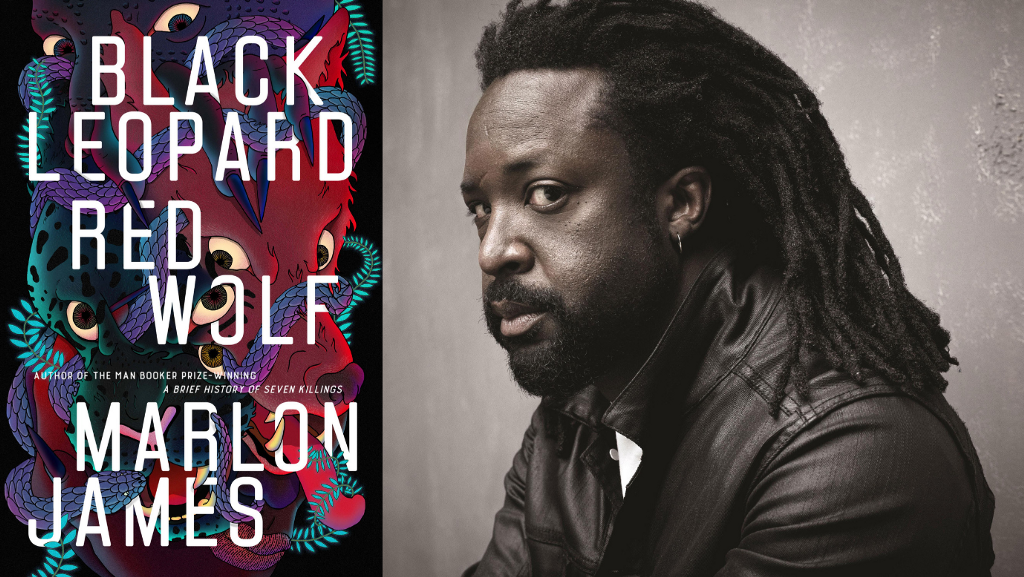

KC: Yeah. I can’t blame my mom for sending me there because a lot of people have this feeling that you have to leave the island to go Stateside for school and for jobs and hope that you’ll be able to return. I think she was trying to prepare me for that. I went to a school that I felt it oppressed my education in that way because it was giving me the “classics.” I never really read a lot of empowering Black literature or Caribbean literature. When I got to school, in the States, which is really ironic, I went to Sarah Lawrence, where there were so many white people. But there were a lot of classes there of Black and Caribbean literature. I feel like that was really my awakening. It had the lyricism of the islands in my blood still when I was writing, but as far as literature, it wasn’t until college that I was reading Jamaica Kincaid and Marlon James. The Book of Night Women definitely influenced Conquered a lot.

JB: Yeah, that sounds pretty similar. I was like, “What were you reading down there? It must’ve been amazing.” “A lot of dead white people.”

KC: On the other schools on St. Thomas, I’m pretty sure it was the same thing. Wherever you go, there’s this system that forces you to think that this is what classic literature is and this is what you have to read. You have to read Shakespeare, you have to read Jane Austen, etc. etc, in order to be considered educated. I should’ve been reading Toni Morrison in high school, not Shakespeare.