The Amazing Adventures of a Certified Medical Interpreter

A second-career medical interpreter for Russian immigrants in Boston contemplates his role—a biblical Joseph? a robot?—and the system that brings him and his clients together.

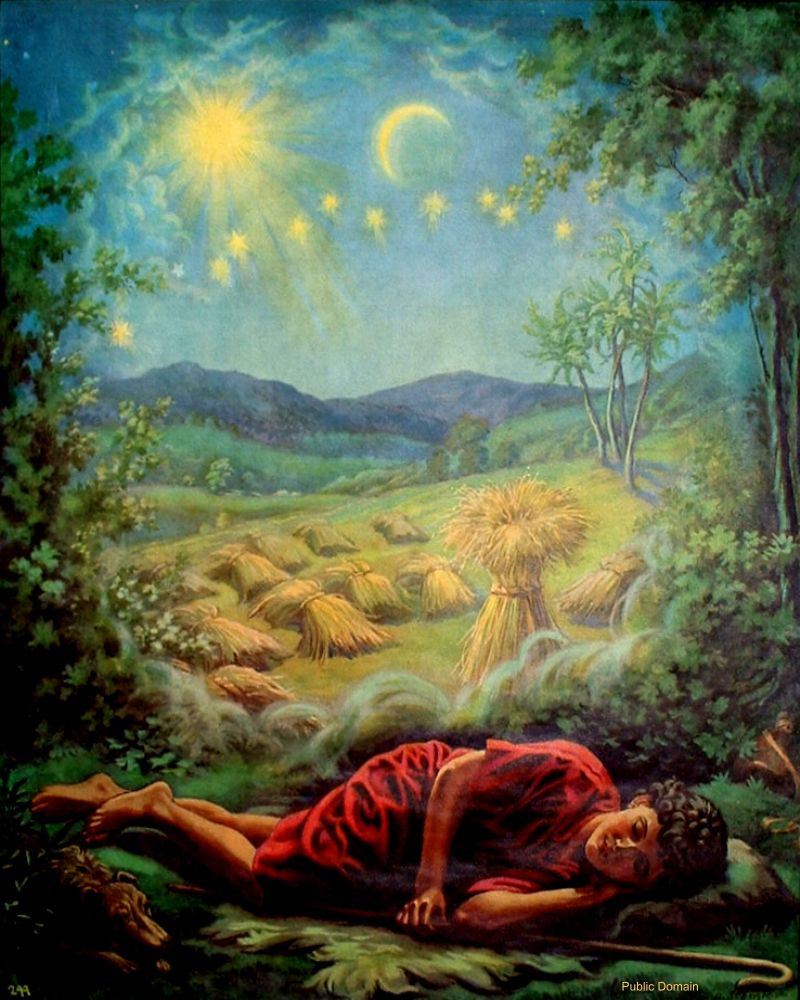

Like biblical Joseph, you are an interpreter of dreams and maladies, with the emphasis on the latter and a fondness for the former. Unlike him, you are nationally certified and have never been sold or thrown in jail.

You were born in the country that professed to be a workers’ and peasants’ paradise but made healthy people sick and then abandoned them. You live in a different country, the one that made a very vocal point of helping the sick, as long as someone pays for it. That someone can be either the sick himself, or his family, or his fellow taxpayer.

You are half-asleep now, after a night full of half-wakened dreams and after a day of maladies at the hospital. One of the few places in America where you can legally and socially acceptably sleep in public is a seat in a subway train, or the T, in Boston-speak.

You sit between two millennials whose eyeballs are, like, bonded with their phones. Last night, your last dream was of driving a bus; its windshield and all the windows were painted black. Luckily, you crashed it before anyone got hurt.

You are lucky again now, returning home after work. You found an empty seat on the T; no one would give theirs up for anyone, even for a pregnant woman holding a baby or a middle-aged man with a lame leg.

You know about the pain. You are a nationally certified medical interpreter. According to the federal Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, at least twenty-five million Americans speak English less than “very well.” They are called LEP, Limited English Proficiency. So they need people like you, who let the doctors and patients understand each other. You are a native Russian speaker, and you are fluent in English, to a degree. After all, you came to this country as an adult.

You were born in the place of shifting borders, good wine, and a deep mistrust for the treacherous and murderous state. Your mother fostered a lasting self-confidence in you, claiming that you learned to read as soon if not sooner than you learned to speak. On the flip side, your family spoke three languages fluently, but you picked up only Russian.

There are many Russian-speaking immigrants in Boston, who joke that Putin will come one day to liberate them, although no one likes Putin here. On the other hand, they vote Republican. In Boston, this citadel of liberalism.

Today, you had to interpret for a Kazakh patient, a native Russian speaker. You talked to her in the waiting room, her toddler playing on the floor next to you, and people looked at you funny. Here was an old white man talking to a young Asian woman in a language other than English. Since you wore a badge and she didn’t, they must have assumed that you were a fluent speaker of an Asian language (you wish).

When people ask about your work and you tell them, some scoff. Of course you are an interpreter. If you know two languages, it’s easy. Being a natural-born contrarian, you jump up, ready to uncoil your long tongue, but swallow your pride instead.

Most medical providers want a nationally certified interpreter. In order to get a national certification, you have to take a course and pass a complicated two-part exam. It’s not only medical terms. You need to know how to deal with fickle LEP and arrogant providers. You need to memorize a sequence of long, rambling utterances you hear in the office—no one wants to stop to make the job of an interpreter easier—and smoothly repeat it in a different language. You need to know the medical laws and regulations. You shouldn’t be afraid of blood, gore, and tears. Besides, you are not a linguist. You have an engineering degree, and you toiled for IBM for twenty-one years. When you lost your job, you retrained. At your age. And all your new colleagues are linguists.

The next patient, a woman in her seventies, yelled across the waiting room as soon as she saw you: “You’re late! Late! I’ve been coming here for twenty years! No interpreter has ever been late.”

She could have argued that the earth is flat or that Boston would vote Republican in the next presidential election with an equal degree of gall.

Good thing the patient yelled in Russian, so no one but you understood her, though the other patients in the room pricked up their ears. The woman was wider than she was tall and had trouble turning over on the examination table.

The interpreter should not editorialize but be a conduit, to deliver the message verbatim, as if he is totally transparent, a man of glass, cleanly washed.

When the doctor came, she yelled at him: “You’re late! Late! I’ve been coming here for twenty years! No doctor has ever been late.”

The interpreter should not editorialize but be a conduit, to deliver the message verbatim, as if he is totally transparent, a man of glass, cleanly washed. You should even maintain the same tone of voice as the LEP.

So you yelled faithfully, “You’re late! Late! I’ve been coming here for twenty years! No doctor has ever been late,” only in English.

Most of your patients came to this country at an advanced age and have no income but SSI. They are brought to the hospital by car services, free of charge, and dread missing the return ride.

Some laypeople call you a translator. You take this error to heart. It’s not only the medium that differs you from the translator. The translator takes her time and must write well in the target language. You have to interpret right away, without using any references. You need to speak and listen well.

The next patient came with his wife. They both were in their sixties. The wife kept winking at you while you interpreted. No one sober had hit on you in the last thirty years, and never in the doctor’s office. You looked at the husband. He smiled a jovial smile. He clearly didn’t notice. Neither did the doctor.

You switched from your role as a conduit to that of the patient’s advocate. That’s a risky thing to do: the provider might get pissed, and it’s the provider who ultimately pays your salary. You took the risk. You told the doctor that the patient’s wife had a confidential message for her. The doctor and you took the wife to another office.

“He beats me up,” she said in Russian, rolling up her sleeve and showing a purple-blue bruise. “I’m afraid of him.”

The service of an interpreter is free for the patient, regardless of ability to pay. A poor immigrant and a Russian oligarch who come here for plastic surgery pay the same: nothing. The medical provider bears the cost.

Sometimes, instead of going to the hospital, you interpret over the phone, through an agency. You can interpret for anyplace in America. You can do it in your pajamas. No T-pass is required and you always have the best seat. But you can’t see the people you interpret for, and they can’t see you, which makes it much more difficult. The poor quality of the connection doesn’t help. And the phone interpreter stands on the lowest rung of the ladder, lower than any clerk. Or you even can do video interpreting. Then people can see you above the waist. But you may still wear pajama bottoms. Business on the top, party on the bottom.

The other day a provider told you to ask the LEP if his smart phone can automatically convert English texts into Russian. You paused for a tart remark. You wanted to say that the year is 2016 and not 2026. You wanted to say that if a program could do that, they wouldn’t need interpreters. You wanted to say that nothing in the world is automatic, and that the humans still have a say. But you thought better. You faithfully interpreted. The LEP laughed. He had nothing to lose because he had nothing.

The LEP usually thanks you but the providers rarely do. You are a member of a service industry. You are invisible.

On the phone, you always start with stating your name and with “how may I help you?” You end up by thanking both parties for choosing your agency’s service. The LEP usually thanks you but the providers rarely do. You are a member of a service industry. You are invisible.

It’s even worse when the LEP attempts to speak in English. They must feel obliged to do that sometimes. After all, they have been in this country for many years and they must brag about their acquired language skills.

They complain about “no discunt” and discuss the novelty of the “porn on the cob.” They broom the kitchen and go forth and back.

One of them called the radiology tech today, “Please, mister guy!”

You checked the tech’s badge. No, his name wasn’t Guy.

The English vocabulary is hard, the grammar rules are even harder, but it’s almost impossible to master the proper American accent when you start speaking English as an adult. And the fact that those immigrants cluster together in the dedicated assisted-living facilities, patronize Russian-speaking businesses and stores, doesn’t help.

Most of them are still pretty sophisticated speakers in their own language in spite of their age. Most are highly intelligent, and even can tell that Clytemnestra killed Agamemnon and not the other way around.

They recognize the hidden mysteries of life. They are two steps ahead of you when you are moving fast and three steps ahead on most of the days. So the harder is the crash when they must switch the languages.

But it becomes really horrible when the provider is speaking with an accent, especially on the phone. Now, you have to struggle on two fronts. It’s a big no-no to tell the provider, “Your English sucks. I have no idea what the hell you are saying. Take an ESL course, dude.” You have to suck it up and blame the connection and your own stupidity.

Sometimes providers speak a little Russian. Most are the victims of immigration—they are the children of the immigrants. They speak in the language of the kitchen and nursery. “Did you fart today?” “How was your pee-pee?” “What was the color of your poop?”

While you are waiting for the doctor in the waiting room, the patients entertain you with their life stories. It’s mostly about kids, grandkids, or great-grandkids. Sometimes it’s their home attendants.

But people over ninety are a different breed.

It seems like someone invisible but determined has removed their wits and health bit by bit with a scalpel and didn’t charge Medicaid for that. Sometimes they can’t even grasp the concept of interpreting, especially over the phone. They interrupt you when you are speaking English.

“Speak louder. I don’t understand you.”

A man who is one hundred years old keeps referring to someone as “this bandit.” You guessed at first it was his noisy neighbor or an uncaring social worker. It turns out he’s talking about President Obama. Another ninety-plus patient refuses to comprehend when you are telling her about her upcoming cataract surgery. “Will they remove my eye?” she wonders.

But sometimes they share Confucius-like wisdom.

“You will improve your IQ dramatically if you stop listening to idiots.”

“Empathy may be like a muscle that requires training. Or it might be innate.”

“Always look through the peephole before opening the door.”

It’s a cliché that medicine prolongs suffering instead of life. But this cliché is lost on them. They prefer suffering to death. They want to live no matter what. They want to be saved no matter the cost.

Now, in the T, you are dreaming about an interpreting robot. It’s so fast that it interprets before the parties say anything. If someone winks at it, it winks back. If someone says something stupid, it faithfully interprets without an internal struggle. And yes, it has a great ear (which is not tin) for the providers’ accents.

The new dream follows in a rapid succession. You must be sleep-deprived. You are dreaming of soldiers protecting their general from the firing squad with their bodies. When the soldiers were mowed down, the firing squad shot themselves rather than the general. That was the informed choice they made, and you approved it in your dream.

You are waking up. Your station is next. A young man across the aisle who just woke up, too, is reading your badge aloud. “Interpreting services.”

Nothing is easy. Life, though popular, is not easy. Death, though even more popular, is not easy. Interpreting either of them is complex.

It’s not in your job description to acknowledge him, but you nod.

“Do you know, like, a foreign language?” he asks.

You nod.

He scoffs. “Of course you are an interpreter. If you know two languages. It’s easy.”

No, mister guy. Nothing is easy. Life, though popular, is not easy. Death, though even more popular, is not easy. Interpreting either of them is complex. You can be thrown in jail for negligence or, like, a HIPAA violation. Or, worse yet, you can have an indelible stain on your conscience.

This country is the only one on earth that gives the patient the interpreting services for free, as far as you know. But someone else pays for it, eventually. Is it socialism with a human face, or just the good old helping hand of a capitalist democracy? Can this be called reciprocal altruism? Is it charity? Common sense? A publicity stunt? You want to discuss this with mister guy. But you are tired. You’re sure he doesn’t care. It’s not his money. Discussions don’t solve anything anyway.

“It’s not easy, man,” you say instead. “Take it from me. It’s, like, certifiably tough.”