When Sarah is triggered, her stomach drops. And then it keeps dropping.

When Sarah is triggered, her stomach drops. And then it keeps dropping.

Her pulse races; her heart hammers in her chest. She starts to sweat, but grows cold at the same time.

Then she can’t see. Her mind goes blank — she dissociates from reality. In that moment, the senior can’t even remember where she is.

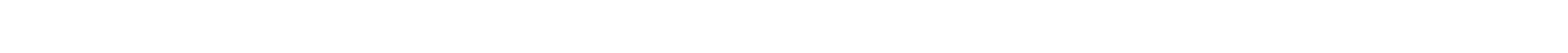

“I feel my clothing, and sometimes I feel my hair,” said Sarah, weaving her fingers through a few strands to demonstrate. “And I realize that I’m a living person, and I’m here, and the sexual assault isn’t happening right now.”

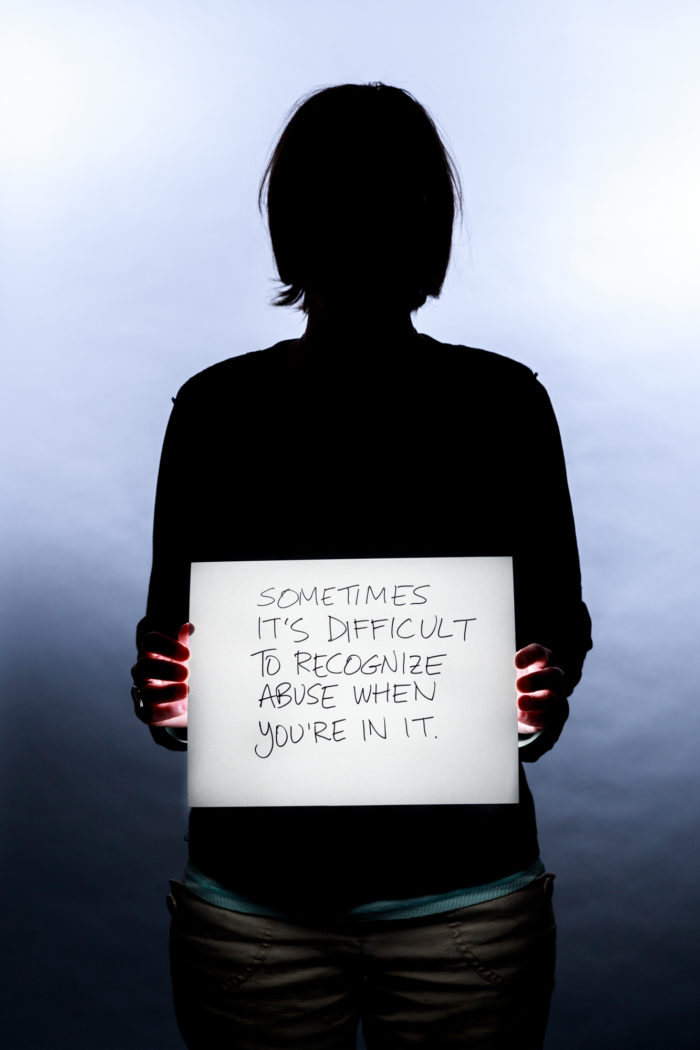

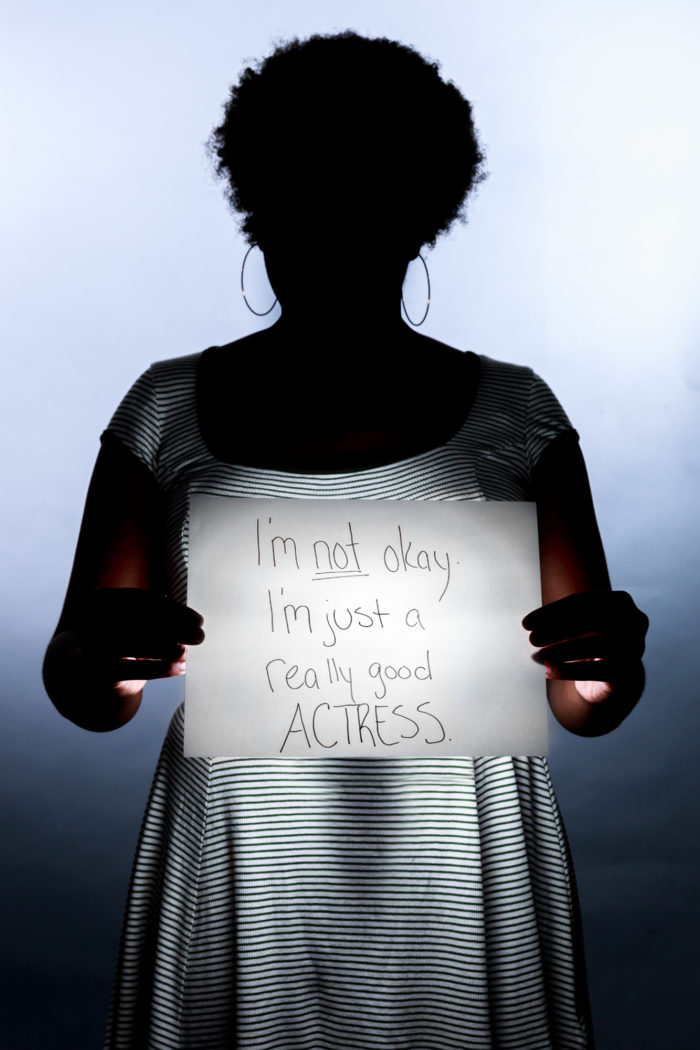

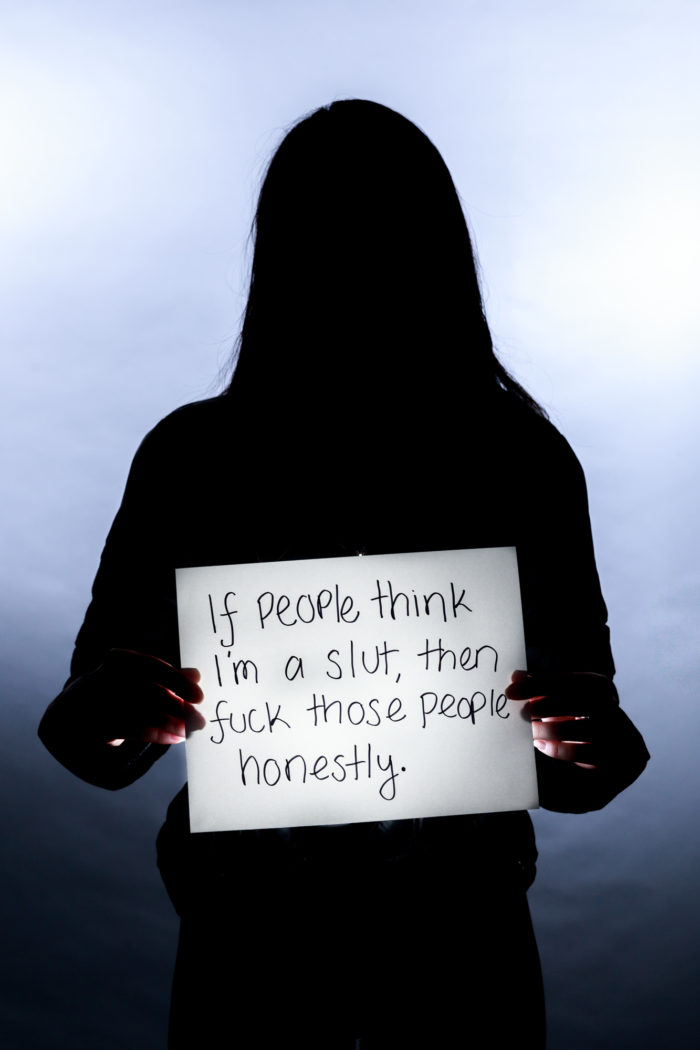

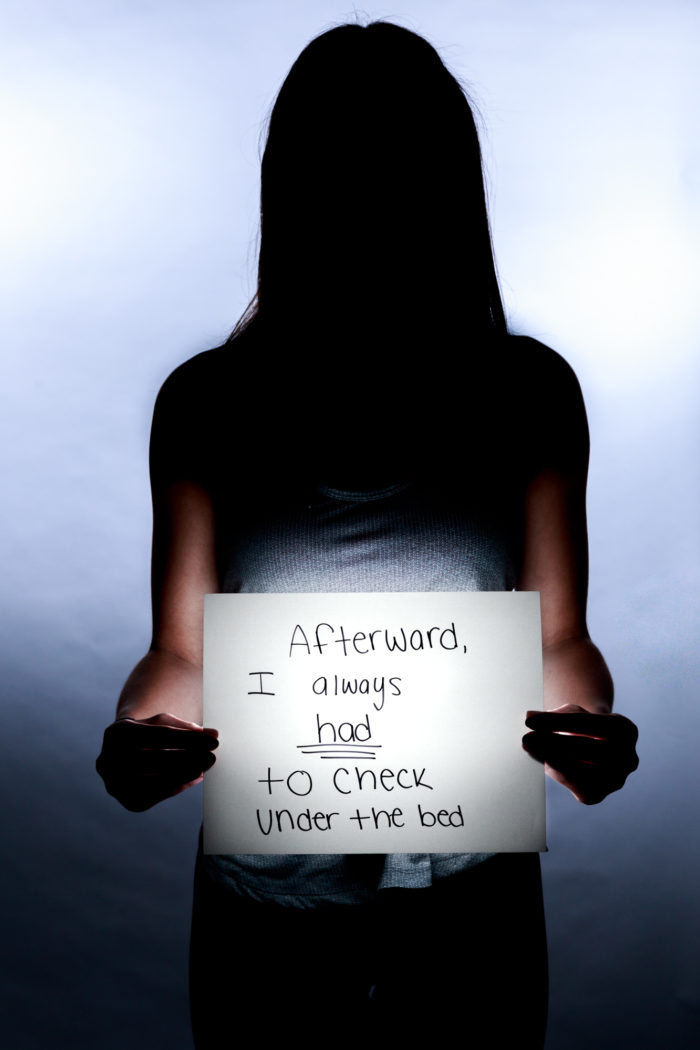

Sarah and seven other sexual assault survivors at the University of Maryland interviewed by The Diamondback for this story detailed the way their trauma lingers as they continue their studies following their attacks. From taking classes with triggering material to sharing the campus with their assailants, many of the survivors said campus life can intensify the post-traumatic stress and anxiety they are already struggling to overcome.

On college campuses, one in five women and one in 20 men said they’ve been sexually assaulted either by physical force or while incapacitated, according to a 2015 Washington Post poll. National statistics also show that assaults are severely underreported.

While none of the eight survivors reported to University of Maryland Police or the Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct, most turned to student advocacy groups, confidential resources on the campus and friends and family during their recovery process.

The Diamondback typically does not name victims of sexual violence. Most survivors quoted in this story are identified either by their first name or a pseudonym to protect their identity.

“Every time someone speaks out about it, it gets a little easier for everyone else,” Sarah said. “Every little voice just chips away at it.”

Antithesis of a safe space

Jessica stopped going to her gender communication course last year after swallowing statistic after statistic, hypothetical after hypothetical.

Jessica stopped going to her gender communication course last year after swallowing statistic after statistic, hypothetical after hypothetical.

Her class frequently mentioned that about “1 in [5]” women are sexually assaulted during college, she said, but the teacher never “looks around and says, ‘OK, so somebody in this classroom has had that experience.’”

“It’s real; we’re talking about people who are here,” the senior communication major said. “… I’m 100 percent of a person. And it’s 100 percent happened to me.”

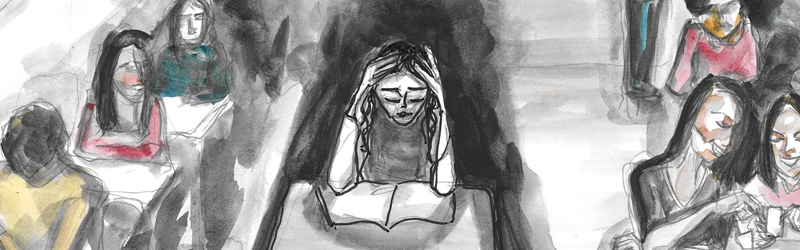

For those affected by sexual assault, classes can serve as the antithesis of a safe space, with course content triggering flashbacks of an attack and discussions magnifying others’ misconceptions of rape culture.

Under federal law, this university’s Title IX office requires an about 45-minute online training for faculty and staff that outlines their obligation to report sexual misconduct claims, what to do if someone “experience[s] or learn[s] of sexual assault” and available resources on and off of the campus, according to the office’s website. In addition to taking mandated compliance training every other year, individual departments can request further sexual misconduct in-person training or presentations through the Title IX office and other campus entities, such as CARE to Stop Violence and the University Student Judiciary, which is overseen by the Office of Student Conduct.

The Joint President/Senate Sexual Assault Prevention Task Force’s sexual assault prevention plan — which university President Wallace Loh approved in late April — also recommended expanding monthly presentations about sexual misconduct prevention and response to include new faculty orientation along with new staff orientation, and encouraged additional training through the Title IX office on “strategies for supporting students affected by sexual misconduct.”

“To create a campus that is free from all forms of sexual misconduct is an ambitious and essential undertaking that is in the interest, and is the responsibility, of every member of our University community,” Loh said in a statement Tuesday approving the Senate task force recommendations.

One strategy that Stephanie Madden, an alumna and former professor at this university, relies on while teaching is using trigger warnings, which indicate a possibly traumatizing scene or topic ahead to help reduce the risk of distressing survivors of assault or any trauma.

For Madden, her personal research and dissertation on sexual assault have made her acutely aware of the importance of triggers, she said — especially after she watched a student have a panic attack in the middle of class in fall 2015.

“I had a student give a persuasive speech in COMM107 about sexual assault on college campuses, and she did not include a trigger warning,” Madden said, recalling how the other student who was triggered had to leave. “… [Trigger warnings are] just giving people a heads-up that this will be part of the topic of conversation and to take care of yourself in whatever way you need to, [whether] that’s excusing yourself from the room for a little bit or the full class.”

Because students’ and teachers’ expectations “vary widely among disciplines, institutions, and levels of study” — and because survivors’ experiences are so diverse — it would likely be “a mistake to enforce any top-down determination that would apply universally” for trigger warnings, Alexis Lothian, a women’s studies professor at this university, wrote in an email. But that doesn’t mean teachers shouldn’t make an effort to respect and appreciate students’ experiences, she added.

Madden noted that some professors can often be out of touch with the extent to which trauma can psychologically affect survivors. Communication department chairwoman Shawn Parry-Giles wrote in an email that she intends to implement in-house training for faculty that broaches trigger warnings next fall.

“Part of it I think is generational in some ways for faculty … the comment [one university professor told] me was, ‘Well, we’re all adults here, we can talk about this,’” Madden said. “But it’s not just sort of adult level of conversation. It is the actual psychological trigger and not being able to control a reaction.”

Turned upside down

Alex’s attacker was a friend. They’d gone on a university ski trip together, and shared a couple of friends in common. But as Alex opened up to mutual friends about her assault, she noticed something: Nothing changed.

Alex’s attacker was a friend. They’d gone on a university ski trip together, and shared a couple of friends in common. But as Alex opened up to mutual friends about her assault, she noticed something: Nothing changed.

Her friends’ continued contact with her assailant added more confusion and hurt to a situation that had already turned everything “upside down,” Alex said. The junior neurobiology and physiology major thought she was prepared to ward off such an attack in the first place, she said, noting how she had kept a small knife attached to her keychain, bought a whistle and took self-defense classes. But none of that mattered when her assailant wasn’t a stranger.

“I was attacked by someone I trusted,” Alex said. “… I thought I knew that guy, but as soon as he had half a chance, he just took advantage of me.”

About 80 percent of college-aged women who have been victims of rape and other sexual assault knew their attacker, according to the U.S. Justice Department. Knowing the perpetrator can often leave victims susceptible to re-traumatization, be it through seeing the assailant on the campus or frequenting the same social circles.

Claire’s attacker has a job at a central location on the campus. Sometimes it’s unavoidable for the graduate student, who identifies by they/them pronouns, to see him, leaving them dissociative and feeling like they’re going to die.

Kate, a senior community health major, avoids fraternity parties and the College Park bars because they remind her of the environment where she was assaulted. She tried to go out for her 21st birthday but had to leave R.J. Bentley’s after about 30 minutes, angering friends who didn’t understand why she couldn’t have fun.

And Sarah Stephens, who escaped an emotionally abusive and sexually violent relationship with her boyfriend more than 20 years ago, still can’t have someone walking behind her on her way to classes. She often has to step to the side of sidewalks to let others — even children — pass.

“I knew school would be hard, I knew school work would be hard … but for me I have this extra added layer of self-doubt [following my abuse] that pops up periodically,” the 41-year-old sociology major said.

On top of experiencing stress and anxiety, survivors who know their assailant can question their worldview and the validity of their experience, said Andrea Chisolm, an assistant clinical professor in the psychology department.

“If they’re raped by somebody they know, they have to make sense of that,” she said. “Sometimes they can start to question what they did, even though they are not to blame at all.”

The Title IX office, the Office of Student Conduct and Resident Life work together to offer interim protective measures such as no-contact orders and housing and academic accommodations — which can include class changes — to sexual assault survivors. There were five housing accommodations, 24 no-contact orders and 26 academic accommodations for 66 complainants from July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016, according to the Title IX office.

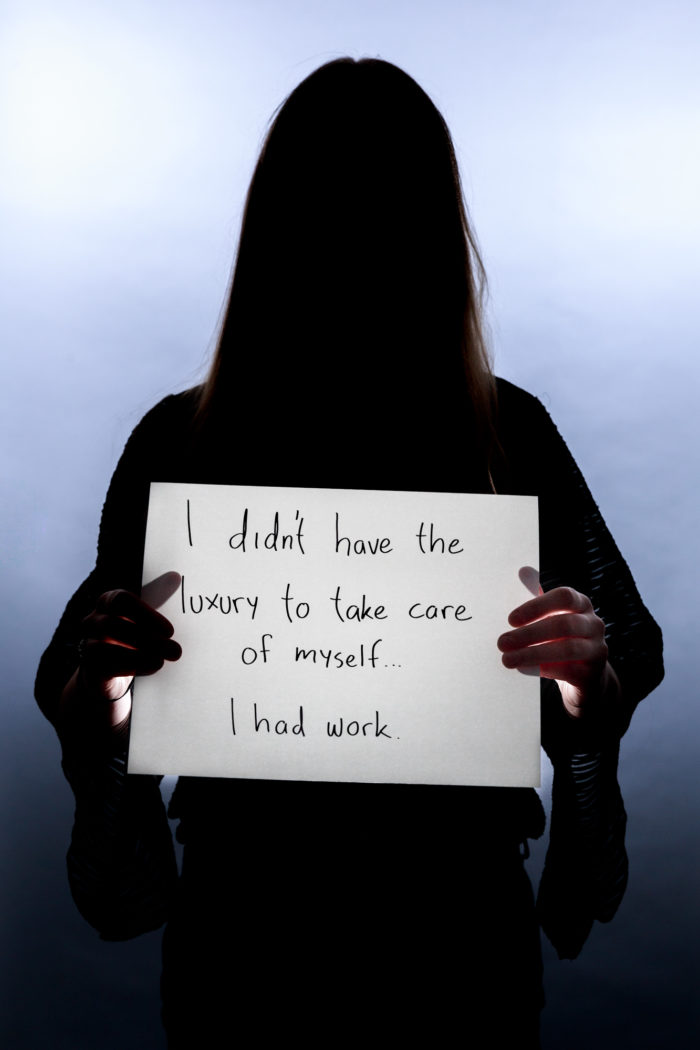

Students who find themselves unable to attend class or who are falling behind on their workloads can also work with the CARE office to send teachers a letter that can disclose generally that they’re dealing with a traumatic experience.

LaVonne Whitehead, CARE’s lead educator, noted that these types of letters mention the University Health Center but not CARE explicitly, so the student is “empowered to have a conversation with as much detail or as little detail as they want with their instructor.”

“The student is able to say what they want, therefore having us step back a little bit,” she said.

Into their own hands

I n November, protesters marched from McKeldin Mall to the Main Administration Building, scattering articles of clothing on the grass and sticking notes to the door leading to administrators’ offices. In February, students crowded into the second floor of Cornerstone Grill & Loft for an intimate discussion on rape culture. And in April, community members congregated on the mall by the hundreds over a 10-hour span to listen to survivors’ stories.

n November, protesters marched from McKeldin Mall to the Main Administration Building, scattering articles of clothing on the grass and sticking notes to the door leading to administrators’ offices. In February, students crowded into the second floor of Cornerstone Grill & Loft for an intimate discussion on rape culture. And in April, community members congregated on the mall by the hundreds over a 10-hour span to listen to survivors’ stories.

Each action was a call for solidarity and increased visibility of sexual assault on this campus, oftentimes gaining momentum with help from Preventing Sexual Assault, a student advocacy group that started in 2015.

“There were so many survivors on this campus who didn’t have anybody to go to, and now it’s kind of like we’re opening up these conversations,” said Alanna DeLeon, PSA’s president and a senior community health major. “… You can’t force people to want to educate themselves until they know the severity of the issue and what’s at stake.”

On a campus of about 38,000 students, Title IX received 21 complaints of Sexual Assault I, or non-consensual penetration, from July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016, while University Police received nine reports of rape during 2015 and 2016, according to uniform crime statistics reported to the FBI. None of the sexual assault survivors interviewed reported their assault to either entity, choosing instead to lean on campus resources or friends and family members.

DeLeon said PSA has played a pivotal role in her own recovery, as members are well-educated on the topic of sexual assault and “have been nothing but great” on days when she has difficulty functioning.

“I can text the PSA GroupMe and ask them to do what I need to do that day, and I let them know I’ll do the same,” she said. “We’re all here for each other because we know how hard it is to talk about this stuff all the time. Even not being a survivor and talking about this all the time is draining. We’re not all superheroes.”

The Student Government Association has also been an active voice in pushing for increased funding for campus resources related to sexual misconduct issues.

In September, the organization proposed a $34 annual student fee for the Title IX office, which Title IX Officer Catherine Carroll described that month as “under-resourced” and “under-staffed.” The charge captured national attention and ended with this university announcing the addition of six new positions between the Title IX and CARE offices.

For those seeking campus resources, CARE serves as a confidential safe space where survivors of assault and sexual violence can walk in during business hours and talk with a trained advocate. This office provided first-time consultations to 117 new clients and scheduled about 650 CARE therapy visits from 2015 to 2016, a university spokeswoman wrote in an email.

Whenever Claire sees their attacker on the campus and starts having flashbacks, they can count on the people within CARE to “do whatever they can to support me,” they said.

“They just do grounding work with me or talk me through it,” they said. “Even though it sucks that I see him, I’m really grateful and blessed to know that CARE exists.”

S exual assault survivors exploring group therapy options can also attend the Counseling Center’s “Hope and Healing” sessions, which served 17 students during the 2015-16 year — up from eight during the 2014-15 school year when the group began, a university spokeswoman wrote in an email. For communities such as minority and LGBT populations, there are also tailored group sessions, including “Circle of Sisters” and “Rainbow Walk-In Hour.”

exual assault survivors exploring group therapy options can also attend the Counseling Center’s “Hope and Healing” sessions, which served 17 students during the 2015-16 year — up from eight during the 2014-15 school year when the group began, a university spokeswoman wrote in an email. For communities such as minority and LGBT populations, there are also tailored group sessions, including “Circle of Sisters” and “Rainbow Walk-In Hour.”

Special services like these can be crucial, especially for those who fear judgment or a lack of understanding, said LGBT Equity Center Director Luke Jensen. Oftentimes, LGBT sexual assault survivors face “double exposure” to shame from being discriminated against as an LGBT person and also being the target of an assault, he noted.

“Hopefully [these resources] convey that whether you’re accessing that particular resource or any other resource in the Counseling Center, there’s going to be some understanding; there’s going to be some knowledge,” he said. “… Sometimes someone can have all the goodwill in the world, but if you’re going to them for help, you don’t want to have to be the teacher.”

For men — one in six of whom enter college as survivors of sexual abuse — assault can also be difficult to address because of pre-existing stigmas and the pervading “female victim-male perpetrator” narrative. Whitehead said the proportion of men who seek CARE’s services is significantly lower than that of women, and the Counseling Center’s Hope and Healing group is open only to female-identifying members, a university spokeswoman wrote in an email. She added that most other group therapy sessions listed on the center’s website are available to men.

Male sexual assault survivors are often left questioning their identity and their masculinity, said Cory George, a male childhood sexual assault victims advocate who was sexually abused by family members as a child. Society raises men to not vocalize their feelings, he said, and to view sexual interactions — with women in particular — as “scoring,” and something to be proud of.

When Sarah is having a rough day and needs to talk to someone “who understands,” she’ll call her mom, Nora. Both of her parents have joined her at some point during her therapy, Sarah said, and know what to say to validate her feelings and make her “feel that I’m worthy, human, even though I just bolted out of a class because I got a glimpse of a four-letter word on a page.”

Although Nora has done everything she can to support Sarah, she said she still often finds herself plagued with questions.

Although Nora has done everything she can to support Sarah, she said she still often finds herself plagued with questions.

“You don’t know how much to press her, how much to let her have her space,” Nora said. “[You ask yourself:] How can I help you best? How can I make you stronger?”

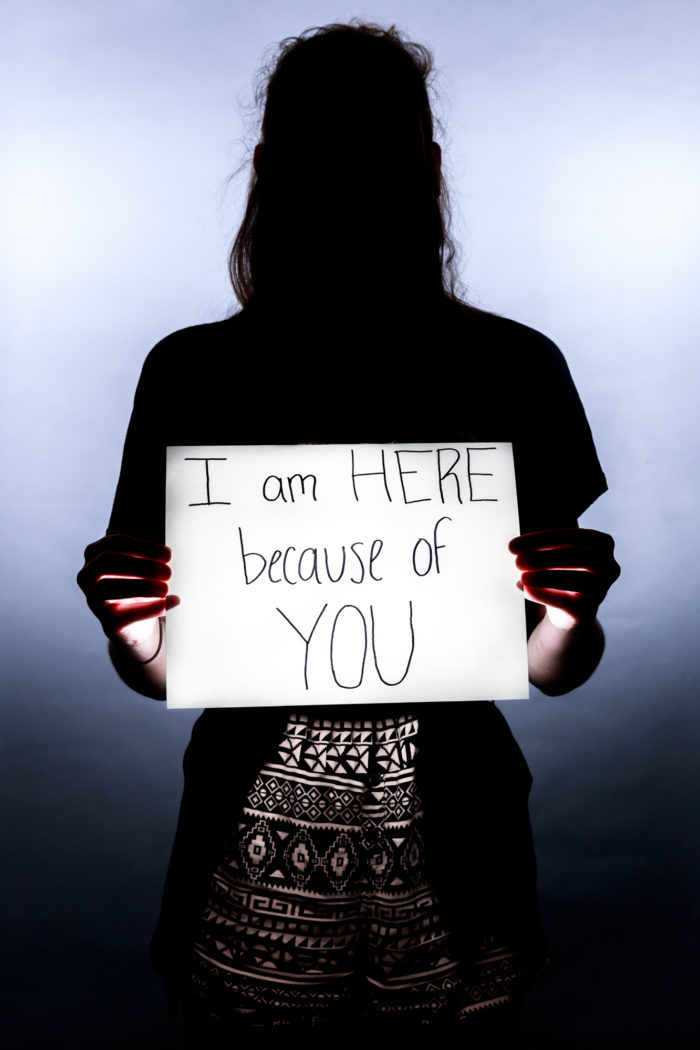

Yet even with help from campus resources and friends, many sexual assault survivors said the residual trauma continues to crop up in their day-to-day lives.

A few weeks after her attack in early 2016, Kate couldn’t go to sleep without checking under her bed or in her closet. She knew her attacker wasn’t hiding there, she said. But until last November, she couldn’t stop.

“It made me feel really uncomfortable and out of control,” she said. “It was this compulsive urge to make sure that I felt safe. … I hated knowing that I had to do this in my own room.”

The trauma can even follow survivors after they fall asleep.

Since Simone was raped in November, the senior finance major has had dreams of being trapped in a house, sometimes with other girls. All of the exits are blocked by brick walls — or by men who bring her back inside.

“I can never escape,” she said. “I try, and I can’t.”