The wind was blowing out.

when the wind blows out at Wrigley, some things happen that just simply can’t

According to whatever official meteorological device was strung up in Wrigley Field on Opening Day, April 4, 1994, the wind was blowing a precise 22 miles per hour, the gust’s trajectory starting near home plate and heading toward the left field bleachers. According to the 19-year-old recollections of Mike Morgan, the journeyman pitcher who got the Opening Day nod for the Cubs that day, the wind was more like 30 or 40 miles per hour. The discrepancy is easy to account for: You can forgive Morgan’s memory a slight exaggeration, since it was first imprinted during a traumatic afternoon when three of his 63 pitches found their way out of the ballpark, before all three booked return trips on the arms of disgusted Cubs fans wanting to send a message rather than take home a souvenir. It is easier to blame misfortune on elements out of one’s control than being forced to criticize one’s own ability, or lack thereof.

But whether the scientific instruments of record or the recollections of a 53-year-old man sifting through the memories of 597 games pitched over 25 years in the majors are to be considered more accurate, the fact remains: the wind was certainly blowing out that day. And when the wind blows out of Wrigley, well, next morning’s commuters on The El reading box scores wouldn’t be wrong to believe the copyeditors accidentally transposed the score of a long-forgotten Bears game. As Morgan’s counterpart was to find out three times on his own, when the wind blows out at Wrigley, some things happen that just simply can’t. And as Morgan’s centerfielder would soon discover, maybe those things shouldn’t.

—

Cubs’ announcer Harry Caray proclaimed a sainted bovine (“Holy Cow!”)

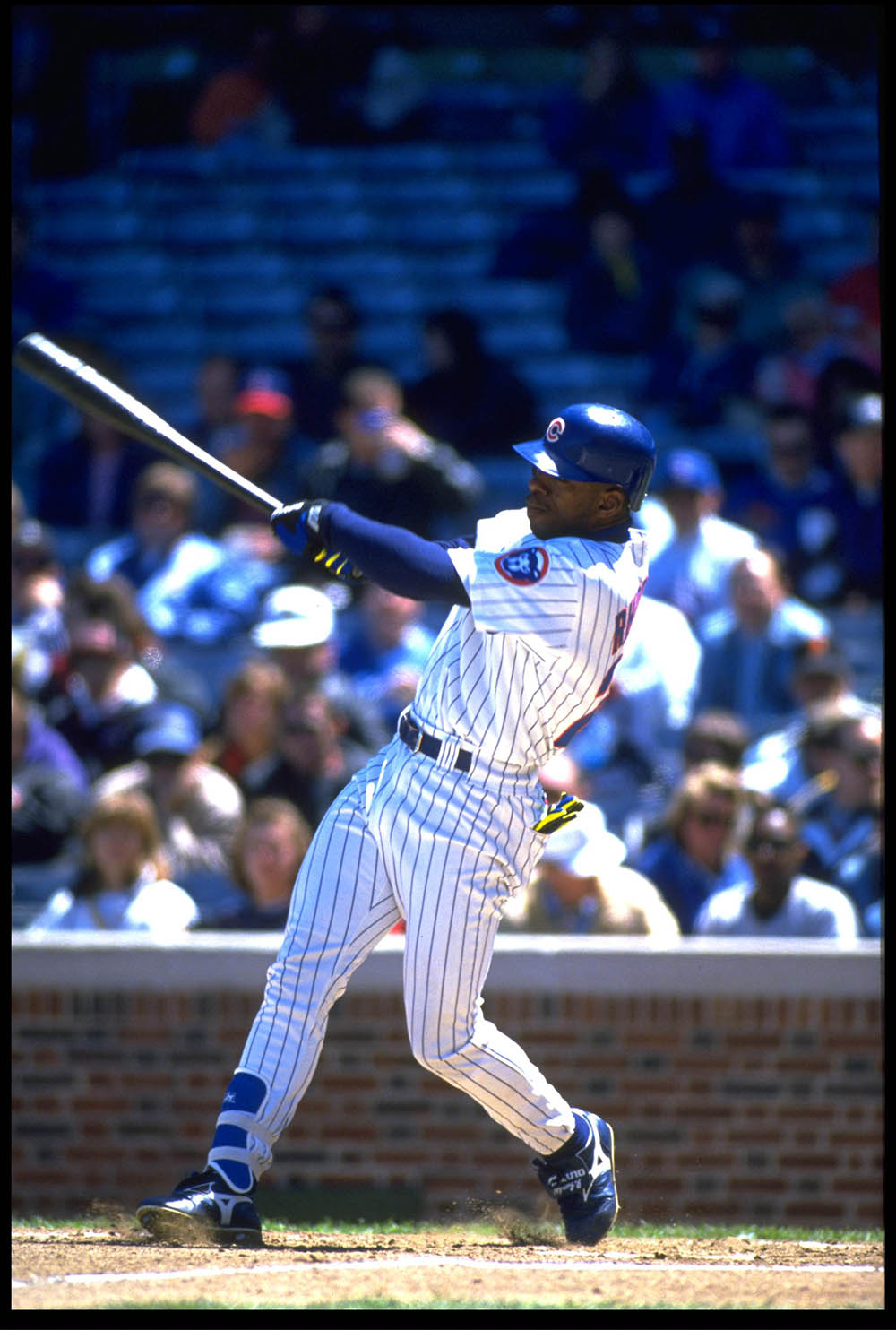

No one quite knew it yet, but Mets’ pitcher Doc Gooden was a mere mortal. The electric stuff that made him a Rookie of the Year and Cy Young winner in consecutive years was gone. His license to make hitters look foolish had been revoked. Now, he was simply Dwight. Still a capable hurler eating innings at a mid-3.00s ERA pace, it was an easy call by manager Dallas Green to give him the coveted Opening Day nod on name recognition alone. But at 29 years old, he was closer to the end than the beginning: a mere three months later he’d test positive for cocaine and be asked to sit out for the remainder of the season; a mere three months after that he’d test positive again and be asked to sit an entire year. But for fans watching the Opening Day tilt between the Cubs and Mets, those mishaps were yet to be written. So while Gooden’s first pitch of the season sailed a bit off the plate, it was understandable that home plate umpire Jim Quick gave him the benefit of the doubt. Newly installed Cubs’ leadoff hitter and center fielder Tuffy Rhodes would be forced to fight back from a 0-1 count. A pitch way up and outside, a high curveball, and a ball low later found Tuffy in an envious 3-1 count before he fouled off a Gooden junk pitch that landed toward the left field foul line, beer-throwing distance from where a head-phoned and bespectacled Steve Bartman would take his seat nearly a decade later.

At 3-2, Gooden threw a curveball that found just enough of the plate to send Tuffy down to the bench. But before it was collected by catcher Todd Hundley, Tuffy’s bat somehow got to the ball, lifting it opposite field into the powerful wind streams created by the archaic contours of the Friendly Confines. The ball landed deep in the left field bleachers, Cubs’ announcer Harry Caray proclaimed a sainted bovine (“Holy Cow!”), and the Cubs were up 1-0.

—

whoever-the-hell simply doesn’t fuck it up, well, the team’s got a shot.

While the most overused comparison to distinguish baseball from football is that between a marathon and a sprint, the more apt simile is between a long-term relationship and a fling: Baseball is a marriage; football is a drunken hookup. Stick with one football team and you’ll get a nice adrenaline rush every Sunday that’s quickly forgotten before the 10 o’clock news. Stick with a baseball team and life will be full of joy, heartbreak, reconciliations, more heartbreak, and a deeper understanding of what love truly is. (Tom Hanks was wrong; there’s a ton of crying in baseball.) This is why it doesn’t make sense that so much stock is put into performances during baseball’s Opening Day. It should simply be the first of 162, but it’s much more than that.

Opening Day is the first unveiling. No matter what a team’s actual chances are, no matter how much the roster has turned over, or what their Pythagorean record predicts, or how abysmal their spring training record, or how many vital ligaments were torn in the process, before they take the field on Opening Day there’s a sense that maybe this really is the year. Fans prognosticate through just the right lens of optimism: Such-and-such is one of the most underrated second baseman in the league, and if so-and-so can throw 200 innings, and who’s-its builds on his rookie promise, and what’s-his-face slugs 40 HRs and whoever-the-hell simply doesn’t fuck it up, well, the team’s got a shot. So, even if they finished fourth in their division the year before, as the Cubs did in 1993, there’s still hope. And with hope comes buzz. And with buzz comes celebrities.

Local heroes are on hand to make quick visits to the broadcaster’s booth. (On that April day in ‘94, Harry Caray asked Olympic gold medalist Bonnie Blair how she gets around without her ice skates.) Politicians show their constituents that, see, they care about these games with balls and goals just like you, the potential voter. (First lady Hillary Rodham Clinton—who, according to always-on-the-prowl Caray, “looks pretty good, doesn’t she?”—was on hand to toss out the first pitch, using an old-fashioned throwing-from-the-front-row-toward-the-mound rather than the more popular mound-to-plate method of delivery.) Awards are given out to players who excelled the previous year. (Since no one on the Cubs had, Illinois governor Jim Edgar settled for proclaiming it Harry Caray Day.) Opening Day is all pomp and circumstance. Excitement’s in the air, beer’s on tap, flyovers are the norm, and beer’s on tap.

in the annals of first-game performances, there’s plenty jockeying for the top spot.

So, sure, Opening Day carries some extra weight. And in the annals of first-game performances, there’s plenty jockeying for the top spot. An argument can be made that Hank Aaron’s home run in the first game of 1974, number 714, which at the time tied him with Babe Ruth for the all-time record, is in control of the conversation. And Bob Feller’s no-hitter in 1940 is certainly holding its own. Mo Vaughn’s walk-off grand slam in ‘98 would be included in most top-five lists, as would Walter Johnson’s 13-inning shutout in 1919. But what makes Tuffy Rhodes’s three-home run game off Doc Gooden so memorable is, in part, how unremarkable the rest of his MLB career was.

”If you told me Sammy Sosa had hit three home runs in his first game, I don’t think people would remember that,” says Cubs fan Joel Turney. Joel is one of my longest friends, despite the fact that he grew up on the South Side of Chicago and still wore a ball cap with a red “C” logo during pickup Wiffle ball games. “But Rhodes came up, hit three home runs, appeared to have some sort of potential, and completely bottomed out.”

But most importantly was what didn’t yet exist: The Internet.

To understand the game’s importance, it’s also necessary to do a little cognitive time-traveling back to 1994: Michael Jordan was currently in his awkward baseball phase, Kathy Ireland was a household name, and Burger King commercials were claiming they don’t “have to be the world’s number one fast food place, just yours.” But most importantly was what didn’t yet exist: The Internet.

Your fantasy team’s scores not only weren’t updated in real time, they weren’t updated unless you or your commissioner did that duty by hand. This meant not every office had four fantasy baseball leagues going; the time barrier for entry in leagues was too high for the average fan. As such, deep baseball knowledge was only for hardcore obsessives or sportswriters. There was just no need for most people to know who the swingman or fourth outfielder was, let alone follow along with stats from spring training. “He wasn’t a power prospect we were expecting a lot of home runs from,” says Joel. “So it was like, where did this come from?” The answer? The Astros, for whom Tuffy had hit three home runs in three seasons before he was signed by Kansas City as a free agent early in the ‘93 season, sent to Triple-A, and ultimately traded to the Cubs in a three-way deal with the Yankees that included luminaries like Paul Assenmacher and John Habyan.

(Fun side-note: A number of fantasy baseball websites still hand out a Tuffy Rhodes Award every year to the player whose early-season performance is definitely not an indication of their year to come. In other words, sell high and sell now.) When I refresh Joel on the other details of the game, telling him that there was nobody on base for all three of Rhodes’s home runs, and that the team would go on to lose the game, like a true Cubs fan, all he can do is laugh.

—

With two outs and the bases empty in the bottom of the third, there was no reason for Gooden to pitch around Tuffy. One home run was just a fluke. Two straight would be miraculous. But still, instead of going right after him, he nibbled the corners. Fastball outside. Fastball high and outside. Breaking ball low and away. Since being awarded the leadoff job in spring training, Tuffy had been studying his predecessors. “I can tell you everything,” the 25-year-old Tuffy told reporters at the time. “I can tell you what all the Cub leadoff hitters did, know how many runs Jerome Walton scored in 1989, and what Bobby Dernier did in 1984 when the Cubs won. This is my job. I’m a professional.” So when he was gifted a 3-0 count, he simply kept his bat on his shoulder. A leadoff man’s job was to get on base, not swing for the fences. He watched strike one burrow down the middle of the plate. With the self- or manager-imposed red light sign unlit, Tuffy was free to do as he pleased. And with Gooden’s next pitch, a fastball low-middle, he did.

While Harry Caray began his home run call with coyness (“It might be, it could be”), another sainted bovine proclamation inevitably came from the Hall of Fame broadcaster. The Cubs and Mets were tied, 2-2. Back in the dugout, Tuffy remained stoic. Sure, he walked back up the dugout steps to doff his helmet when the fans demanded their curtain call, but he did it without the slightest hint of a grin. “Smile, Tuffy!” Caray urged from the booth. “Come on!”

—

But all of that losing doesn’t necessary spoil the fun for Cubs faithful.

According to the advanced Sabermetric stat Win Probability Added, a highly-advanced formula that I’d do my best to steer clear from explaining other than to say it breaks down the importance of each at-bat by assigning a positive or negative number—positive means the player’s team has a better chance of winning after the at-bat in question, negative means otherwise—Tuffy’s second home run is his only at-bat that registers in the top five for the game. That’s because most of the other big plays came on the Mets’ side of things, seeing as they went on to win the game 12-8.

”I think we all figured, ‘How very Cub,’” writes Al Yellon, long-suffering Cubs fan and managing editor of Bleed Cubbie Blue who attended the game. When you haven’t won a championship in 105 years, that’s the normal reaction.

”I think the average Cubs fan, when you start talking baseball, they start chronicling devastating losses,” says Joseph Reaves, a Cubs beat reporter for the Chicago Tribune back in ‘94 before heading off to more championship-friendly pastures as Director of International and Minor League Relations for the L.A. Dodgers. Reaves, a fan before he made his living covering the team, quickly mutters through a list of Cub-induced heartbreak: The Ron Santo black cat game, Steve Bartman, a lesser-known affair in ‘92 wherein manager Jim Lefebvre ran out of players in extra innings. “He had no one to pinch run for Kal Daniels, who was basically crippled at the time,” still complains Reaves, “and he gets thrown out at the plate for what would have been the tying run. These are the games I remember.” But all of that losing doesn’t necessary spoil the fun for Cubs faithful.

“When I got called up in ‘93,” Tuffy said recently, “we were 15 games out of .500. But still 35,000 people were in there, in September, in the cold.”

Growing up as a White Sox fan, as I did, there’s a certain chip-on-your-shoulder reserved for fans of that team up north, the one consistently outdrawing your more recently-betrophied heroes playing in Comiskey/U.S. Cellular, the one with the WGN Superstation proliferating losses to all corners of America, the one Bill Murray chose as his own. How could a team that has such a rich history of losing have supporters? And my, how many! To justify this seeming contradiction, us Sox fans came up with our own admittedly passive-aggressive theories: There are no Cubs fans, only Wrigley fans; the sellouts are because businesses bought season tickets to impress visiting stock holders; none of those fans know their stats; the bleachers are full of frat douchebags watching games on their rich parents’ dime; after all, how can all of those day games sell out, when real people have jobs?

But the older you grow, the less grudges you hold. (Or, at least, you hold them for more valid reasons.) And the realization slowly leaks in that there is, indeed, a true fandom lurking inside that old stadium. Nobody wants to be associated with a loser from birth to death, but at some point, your lot is cast and that’s that. All you can do is hope and pray and root, root, root. And study up on your stats just to laugh at the ridiculousness of it all.

”I looked this up for you,” writes Yellon. “There have been 514 games in MLB history since 1916 where a player has hit three or more home runs. That player’s team lost just 85 of those games. Eleven of those 85 were by Cubs hitter. To which I, as a Cubs fan, say, ‘Figures.’”

—

Pitchers are taught from a young age that if the batter seems too comfortable—and there’s no more comfortable hitter than one who hit home runs in his previous two at-bats—then you have to do something to make them uncomfortable. Force them to move their feet a little, or maybe get them to consider, for an extra split second, that there’s a rock-hard projectile coming toward their unguarded body at 90-plus miles per hour. So, of course, after two straight home runs Gooden decided to come in with a fastball high and tight to Tuffy. Waste a ball just to send a message. The true at-bat wouldn’t start until the second pitch, Gooden figured. But on that 0-1 count, Tuffy decided to end it.

“Can you believe it?” loudly asked Thom Brennaman, who took over for Caray in the booth during the middle innings to give the old man a break. Tuffy, once again, lofted a Doc Gooden fastball toward opposite field and let the wind do the rest, cutting the Mets lead to 9-5. Finally, in the dugout after his second curtain call of the day, Tuffy smiled. “It took a hat trick to do it, but he finally did,” said Brennaman, as fans started throwing their caps onto the field in celebration, echoing the NHL tradition. “You don’t want your leadoff hitter hitting three solo shots,” opined Brennaman’s partner in the booth Steve Stone, before ominously wondering, “I don’t know how long this leadoff man stuff is going to go.”

—

“I got caught up trying to hit home runs.”

“I got caught up trying to hit home runs,” Rhodes, now 44 years old, tells me.

This is the danger of mistaking correlation for causality: You start believing that you are in control. It wasn’t the fierce Wrigley wind that caused those three balls to leave the park; it was a change in a swing or a shifting of a stance. And once that belief sets in, efforts are focused on duplicating that swing, trying to recreate those perfect set of circumstances, ignoring what made you so valuable in the first place.

“The funny thing is, the next day I hit a ball just as hard, but the wind was blowing in and it ended up being a fly ball to left field,” he says. “I knew that would have left the ballpark if I hit it the day before.”

While Rhodes started 1994 hitting six home runs with a .313 batting average during the month of April, his good fortune quickly evened out. During May, he only hit one home run to go along with a .194 average. As baseball players are wont to do, Rhodes tried to counter “bad luck”—in reality, his true skill set was probably somewhere between the two outliers—with some good. He wore stirrup socks exposed to the knees during batting practice while in the midst of a 1-for-22 slump. When that didn’t work, he commissioned teammate and clubhouse barber Glenallen Hill to shave his head. “I did it so I’d be more aerodynamically sound,” said Rhodes at the time, “maybe it’ll add a few more inches onto my line drive.” But on June 13, Rhodes was hit with a devastating blow that he’d not recover from.

“When Ryno retired, he threw me for a loop,” says Rhodes. Ryne Sandberg, his teammate and Cubs’ two-hole hitter, shocked the baseball world by announcing his retirement, effective immediately, citing dissatisfaction with his mental approach. “He’d teach me about pitchers from other teams,” says Rhodes, “their tendencies, what to look for, how to be a student of the game.” And without Sandberg’s calming hand, and when the magic of the superstitious acts didn’t take, Rhodes’s career spiraled. Down.

“It was clear the guy was dead-weight,” says Reaves. “[Manager] Tom Treblehorn did a nice job of letting him down as easily as he could.” First, Treblehorn took away his leadoff spot, writing Sammy Sosa’s name at the top of the lineup card instead. On June 20, the other half of Rhodes’s value was ripped away when Hill started his first game in center field. Rhodes never got the spot back. “I didn’t take too kind to that,” admits Rhodes. Tensions boiled over. A report surfaced 10 days later regarding a fight with the team’s strength and conditioning coach. “I was kind of stubborn, I guess.”

From the point when Hill took over in center field, until the day baseball died that year when players went on strike on August 11, Rhodes played in 31 games, starting only seven of them. During that stretch, he hit one home run for a single RBI and went 0-for-1 in stolen base attempts. “I just didn’t do my homework,” he tells me. “I was a young kid who was successful without really thinking about the extra work. I wasn’t scouting the pitcher, wasn’t scouting the coaches.”

It was his last at-bat in the major leagues. In Fenway that night, the wind was blowing in.

He came into 1995’s spring training needing to earn his spot on the Cubs, which he did, but only as an occasional pinch-hitter or defensive replacement. On May 26, the team placed him on waivers and he was picked up by the Boston Red Sox, who gave him only a few sporadic at-bats. His last one came on June 8, pinch-hitting in the ninth inning against California Angels closer Lee Smith, who got him to pop a lazy foul fly-out to shortstop on the second pitch. It was his last at-bat in the major leagues.

In Fenway that night, the wind was blowing in.

—

Consider the situation: You’ve hit three home runs in your first three at-bats of the season, a feat that’s never been accomplished before. There are two outs, two runners on, and your team is down by three. In other words, if you hit an unprecedented fourth home run in a row, you’ll tie the game. But before the at-bat, the opposing manager removes the pitcher off which you’ve been having your success, instead making you face a 6’10 left-hander. And this lanky new pitcher, Eric Hillman, not yet in the groove, starts you with three straight balls. You redo your batting gloves, look toward your coach for a sign alerting you if you’re allowed to swing on a 3-0 count, and begin thinking of yourself in historic terms. Many before have hit three home runs in one game but, at that moment, only a dozen of the thousands of men to have ever played in the major leagues have hit four. So even if your coach gives you the proverbial “red light,” if you end up taking a hack on a 3-0 count, no one’s going to blame you. How could they? The Gods were smiling on you that day, after all. The fourth pitch is delivered and it’s right in that sweet spot, a tad high, maybe just out of the strike zone, but in a perfect place that would make it so easy to elevate, just a tad, to loft it into that wind tunnel that’s been so kind to you. Do you take the swing?

Tuffy took ball four. The bases were loaded for the power hitting Sandberg, who lined out to deep left field, ending the threat.

—

The trick to life is looking at the entire picture, all the ups and downs, not just dwelling on one particular section.

The trick to life is looking at the entire picture, all the ups and downs, not just dwelling on one particular section; that’s the danger of putting too much stock in a small sample size. It’s looking at the really awful times (a bad year at the office, a protracted divorce) and giving them the same weight as the good stuff. It’s having the knowledge that if you’re currently having a rough go of it, you just need to wait it out. Things have been better before, and they will be again. Get through this bad chunk and, soon enough, you’ll be starting your next Second Act.

”I got a call in the offseason from my agent who said, ‘I got some good news and some bad news.’” Tuffy tells me. “I said, ‘Give me the good news,’ and he said there was a team that wanted me to play every day. And I was like, ‘OK, what’s the bad news?’”

The bad news was that to get those every day at-bats he’d have to pack his bags and travel the 6,800 miles from his home in Houston, Texas to Osaka, Japan. The team that called was the Kintetsu Buffaloes, a red/navy blue/white-uniformed ballclub playing in Japan’s Nippon Professional League. Agreeing to play there would be an admission of failure, a settling for second best. “But once he told me the offer, I was like, ‘Where do I sign?’”

Instead of seeing the trip as a demotion, he saw it as a great opportunity. “I was going to learn how to play baseball in Japan and stay there as long as I possibly could.” That meant diving head first into a foreign culture, learning the language, finding the subtle differences between the two versions of the game, and, this time, doing his homework. He started writing down notes on all the pitchers he’d faced, going through sequences pitch-by-pitch, trying to detect any patterns. It was tough, because pitchers in Japan throw anything at any time.

He became the all-time leader in home runs for foreign-born players with a whopping 474 to his résumé.

“Baseball in America is like checkers, and baseball in Japan is like chess,” explains Rhodes. “You get the leadoff guy on in the first inning, second guy’s going to bunt. You even have suicide squeezes with bases loaded/no outs. Baseball in America, you go 3-0, 3-1, 2-1 and you’re getting a fastball. In Japan, you can get anything. A slider, forkball, change-up—anything. Anything to get you out.” But at some point, after putting in enough work, Rhodes figured it out. “One day, I was hitting with no outs and a 3-0 count, and I stood there and said to myself, ‘This pitcher is going to throw a curveball.’ And he did and it went for a grand slam. I figure I’d arrived.”

Rhodes’s next 13 seasons in Japan, spread out across the various incarnations of the Buffaloes and the Yomiuri Giants, are the stuff of legend. He became the all-time leader in home runs for foreign-born players with a whopping 474 to his résumé, tied for the 10th overall ever to play in Japan, and drove home nearly 1,300 runs. “Everybody knew who I was,” he says. “I was considered the Barry Bonds of Japanese baseball.” He even brought some fire to a, let’s say, more polite brand of baseball: He became the all-time leader for career ejections, with a grand total of nine. But in 2009, he decided to hang up his cleats for good to head back to Houston to spend time with his son, Tuffy Jr.

“I’ve been away for 15 years, so I’m playing some catch up,” says Rhodes, who coaches his son’s basketball team in-between getting the high school senior prepped for college. And once T.J. heads off to school next year, if Rhodes gets a call from a Japanese team? Well, the 44-year-old isn’t making any promises, but he’ll pick up the phone. “I’ve turned them down because I’ve been so focused on his life,” he says, “but maybe I can start going back over there.”

And sure, every now and then, Rhodes sinks into his memory to soak up some lingering good feelings from his best game as a professional baseball player. It’s just that when he lowers himself into the mental bath, he isn’t drifting in that afternoon at Wrigley. He’s, instead, floating in a game from September 25, 2001, when he hit home run number 55 off Daisuke Matsuzaka, tying the single-season home run record with Japanese legend Sadaharu Oh. (To give you some sense of how long that record stood, Oh hit his 55 in 1964, meaning the 37-year span between Oh and Rhodes is equal to that between Roger Maris and Mark McGwire.) It was the icing on a season that ranks with any ballplayer’s, on either side of the Pacific: Rhodes set Pacific League records for home runs, runs, and total bases, ultimately taking home an MVP award for the year. But the best part about that game in ‘01, the biggest thing that sets it apart from the three-home run outburst off Doc Gooden on Opening Day in ‘94?

”We won the game,” says Tuffy.

—

Tuffy’s fifth at-bat on Opening Day in ‘94 may have actually been his best. Leading off the ninth inning of a 12-7 game, crowd on their feet looking for magic to strike a fourth time, Rhodes took a ball high from Mets closer John Franco. On the second pitch, he tried to give the fans what they wanted by uncorking a swing for the fences. Swing and a miss, strike one. On the third pitch he went back to basics, shortening his swing and fouling one off.

On the 1-2 count, Rhodes took his smoothest swing of the afternoon, smacking a line drive into short right field, flashing the gap-to-gap stroke that got him into the majors and earned him the leadoff spot in the lineup in the first place. In any other ballpark, on any other day, in any other league in any part of the world, that would have been a solid base hit no matter what kinds of tricks the wind was pulling. His final box score for the day: 4-for-4, three HRs, three RBIs, three Rs, one BB, a 1.000 batting average. Perfect.

—

He realizes that no matter how many accomplishments are to come, however many roads he has yet to travel, that this moment is the one he'll be remembered for.

There’s a shot from the broadcast of the game that’s stuck with me. It’s right after Tuffy rounds the bases following his third home run, after he gives the fans their second curtain call, while the grounds crew patrols the outfield, picking up the dozens of ball caps that have been thrown in his honor. After an initial round of high-fives and “We’re not worthy” salaams from his teammates, they let him be to soak in the moment. Sosa stalks the foreground, already an expert in when WGN turns on their dugout-facing camera, already perfecting his kiss-two-fingers-chest-bump salute that will become so iconic a few years down the road. And behind him, sitting next to bank of red batting helmets, Tuffy smiles. Remember, it’s his first smile of the day.

The camera takes another angle—casting attention-hog Sosa aside—and zooms in on the man of the hour, and the smile is already gone. Tuffy nervously tugs at his small tuft of chin hair, he itches his face, scratches his mustache. Really, anything to keep his hands occupied. “He’s going to leave an indelible impression not only on one Doc Gooden, but the entire National League when they read about what he did this afternoon,” says Brennaman. A tear seems to form momentarily on Tuffy’s eye before he takes a deep breath and wills it away.

And he knows. You can see it in his face, he knows. He realizes that no matter how many accomplishments are to come, however many roads he has yet to travel, that this moment is the one he’ll be remembered for. And there’s a happiness that comes with that realization, sure. How could there not? He’s just put on a display that will be remembered with some of the all-time greats. But there’s also a lingering sense of dread creeping in. If this is his moment, if this is the peak, then what’s on the way down?

It’s merely Opening Day, after all. Anything can happen over the next 161.