Whatever Happened to the Phone Phreaks?

Phone phreaks demonstrated that the mundane telephone could become a gateway to virtual adventures which spanned the globe, anticipating the culture of hacking today.

"Let's say a shopping center," says the hacker I'm talking to online. He's British, but is using an alias, 'Belial', and I don't know his real name. "The elevators or lifts inside have emergency telephones and these telephones are attached to the PBX [a small telephone network for a building or business]. The speaker inside the lift has an extension like a phone would and you can dial the phone inside the lifts.

"You can monitor what's going on inside, so you can hear the lift saying 'you are on the third floor'. And you can hear people walking in and out, and you can speak to them and prank them. You can say, 'Due to technical issues, we're going to have to cut the cable on this lift, we apologize for any inconvenience this may cause you,' and stuff like that."

He chuckles a bit at this. And I confess that I do too. Belial experimented with phone phreaking in the 1990s as an Internet-curious teenager. He tells me that finding access to things like telephones in elevators was at the time a matter of using computers to "scan" sets of hundreds of numbers for what he terms "gems" -- call destinations (such as people's hotel rooms) which were worth exploring with a little creativity.

This is the point at which "phone phreaking" (hacking the telephone system) and the modern sense of computer hacking intersect. This, essentially, is phreaking's twilight. But where did the practice of accessing internal numbers, or making long-distance calls for free, or setting up phreak "conferences" that could endure from dusk till dawn actually begin? And what is left of it all today?

To answer the first question I spoke to Phil Lapsley, author of a brilliantly researched new book entitled, Exploding the Phone: The Untold Story of the Teenagers and Outlaws who Hacked Ma Bell.

Early in our interview I ask Lapsley what his personal favorite stories about phone phreaking are. Without much hesitation, he says, "the early days." "The early days," in this context, refers to phone phreaks of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Many of them were students at top universities like Harvard. Others were gifted engineers.

A few still were blind kids with perfect pitch like Joe Engressia who, through whistling into their telephone at precise frequencies, found ways to unlock a vibrant world of interaction and exploration within which natural sight became irrelevant.

"These people kind of crystallise what I love about this subject," explains Lapsley, "Which is simply the combination of innocence and curiosity. These were not people who were out to make free phone calls, you know, for the sake of making free phone calls. They were just like, 'Wow, what happens if. What happens if I dial this number? What happens if I play this tone?' They were simply curious."

Few capture this sense of wistful curiosity better than 'Captain Crunch'. Like Joe Engressia, Captain Crunch was interviewed in depth for a lengthy 1971 investigation into the world of phone phreaking published by Esquire magazine. This piece later became famous as the document with which Steve Wozniak introduced his friend and future business partner Steve Jobs to phone phreaking before they experimented with the phenomenon themselves.

In the Esquire article, Captain Crunch narrates excitedly to his interviewer Ron Rosenbaum the process by which he connected a single long-distance call via switching stations across Asia, Europe, South Africa, South America and the East coast until he reached a specific telephone in California.

Captain Crunch had in fact wrapped his call the entire way around the globe, for the ringing phone he had been patched through to was one right beside him -- his own second line. Crunch picked up the other receiver and listened to his own voice. "Needless to say I had to shout to hear myself," he told Rosenbaum, "But the echo was far out. Fantastic. Delayed. It was delayed twenty seconds, but I could hear myself talk to myself."

Lapsley and I discuss the idea that it was activity like this which brought us the modern paradigm of a hackable worldwide network. That is, a place full of strange, wonderful and sometimes dangerous things within which people were free to communicate and explore as they saw fit.

"It becomes a playground," Lapsley says, describing phone phreaks' determination to access remote or unusual telephone switchboards. "It becomes a question of... how far can you go. 'How close can you get to the north pole?' That's a game some kids used to play. 'Let's pick a spot to see how close we can get to it.' It becomes in some ways like virtual tourism and there's an infinite chain of puzzles. ... You can keep playing this game over and over again."

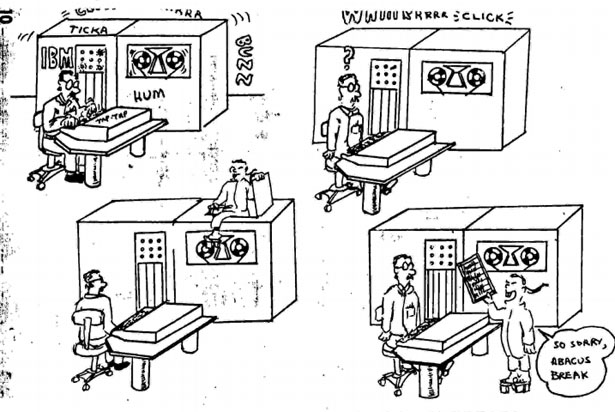

At this point Lapsley makes a salient observation. He notes that, with the rise of personal computing, it was generally thought that the "killer app" of computers would be software which would deliver some intelligence or insight to help us solve some problem or other.

"These people kind of crystallise what I love about this subject," explains Lapsley, "Which is simply the combination of innocence and curiosity. These were not people who were out to make free phone calls, you know, for the sake of making free phone calls."

"What turned out to be the killer app was people, right?" argues Lapsley. "It turned out to be people connected together via computers. Email becomes the killer app, or Twitter for example, and all these things are what people get excited about because what people really care about, it turns out, is other people."

Thinking about this, my thoughts turn to the writings of Jason Scott, a well-known hacker and Internet archivist who experimented with phone phreaking in his teenage years.

In 2006 he wrote about how he and fellow hackers would phreak their way into teleconferencing systems in order to have all-night group discussions -- always at the expense of someone else (a client of the teleconferencing company).

Scott summed up the vitality of these underground tele-meetings like this: "The difference between a two-party call and a telephone conference was like the difference between a Sno-cone [sic] and skiing. And the best part was how sometimes the conference would come to you, unannounced, just you picking up your ringing phone and a dozen people would call out your name and drag you into the never-ending conversation."

And in another post, he encapsulates beautifully the precise place at which he discovered his own hacker gene: a phreak-friendly payphone a few hundred yards from his house in Brewster, NY: "[It was] a classy, self-contained room that a young fellow spent his youth w[h]iling away the hours in, trying beyond all reason to be somebody different, somebody more powerful, a unique force at an age when you feel anything but."

When I spoke to Belial about how phone phreaking and computer hacking intersected, he echoed this sense of self-discovery and exploration. His goal had been to use phreaking techniques to connect to foreign computer terminals and access BBS (bulletin board systems --- like notice boards for the early Internet).

"It enabled me to be able to dial systems over a longer period of time without ever worrying about a phone bill being expensive," he recalled. "And I guess as a result of that it enabled me to have a wider view on the world, and be able to exchange information with people from Singapore, you know, all the way to New York and anywhere. And as a teenager growing up there were no border boundaries."

As phone companies clamped down on this activity, however, being a phone phreak meant coming up with savvier ways to connect to remote systems. Cruder methods whereby specific frequencies (like 2,600 Hz on US networks) could be used to surreptitiously make connections were eventually stopped when Western phone companies began to install digital filters that could recognise these attempts and block them. "You could blast away all you wanted and you wouldn't be able to get anything out of that switch at all," remembers Belial.

This coincided with the rise of "war dialling" (automatic scanning of numbers) and the creation of software which could use sophisticated, lightweight methods of finding switchboards, often in developing countries, which remained susceptible to phreaking. Belial tells me he knew many 1990s phreaks who he claims essentially had "full control" of such foreign exchanges and could route Internet traffic "any way they wanted." He adds, "It was quite a significant power to have."

These stories of latter-day phreaking via remote telephone exchanges is corroborated by another hacker with whom I make contact. He uses the pseudonym '10nix' and tells me: "I remember some years back there was this switch up in Livengood Alaska (population 29) that still responded to 2,600 Hz, and could be blue-boxed [gaining control over a connection via a device which transmits specific sequences of beeps and boops to the network]. [...]

"I remember getting such delight in calling a number that was not in service, playing 2,600 Hz into the phone, and hearing the switch chirp back. I still have a recording of it somewhere."

But hackers like Belial have still been able to acquire reams of new information through what are essentially just updated phreaking techniques. Belial tells me, for instance, that for a period of "about five or six years" he ran a program to listen for and decode pager messages from the telephone network in Britain.

He explains that he amassed a "significant" amount of them. When I ask what kind of number he's talking about he replies, "Eh, probably something in the region of 21 million."

From automated computer system updates configured by IT administrators to ambulance dispatch commands, Belial claims to have captured a fascinating cross-section of 1990s British telephone network activity. He even put all the messages into a database for his own reference. This allowed him to cross-check computer systems he wished to access since he could look up specific IP addresses and machine information. "As a result I was able to find a large amount of access [codes] -- user access, administrator access -- to telephone conferencing systems for large organizations and multi-nationals."

Phone phreaks demonstrated that the telephone, a seemingly mundane device, could become a "gateway" to virtual adventures which spanned the globe.

Belial says he now works professionally in high tech security and tells me that he has, in the past, disclosed system vulnerabilities to organisations potentially at risk. But he comments that such disclosures are rarely taken seriously -- perhaps a symptom of a culture which today can't imagine that telephone systems are really anything to worry about, even though they can to this day provide hackers with access to internal networks.

Since phreaking began with making free calls which shouldn't have been free, it has always occupied a difficult legal space. Phil Lapsley, in his book, charts the herculean efforts AT&T went to over the decades to prosecute and discourage phreaks (and criminals, who often bought blue-boxes) from sponging on their network.

But when I so much as allude to this in an email to 10nix he provides, in no uncertain terms, his view on this issue: "Phreaking has always been about finding and figuring out. It is a disservice to the pioneers of the craft to characterize the goal as theft. The theft was more of a means to an end, and not the goal itself."

In the world of hacking, where interpretation of the law is necessarily somewhat flexible, phreaking and legendary individual phreaks like Captain Crunch have achieved cult status. Depending on who you ask, phone phreaking is either "a dead art" or alive and well even if it "looks different" now.

However, everyone I talked to had a great deal of respect for the global telephone infrastructure, whether or not they had a positive opinion of the companies who own parts of it. As Phil Lapsley put it when I talked to him, phone phreaks demonstrated that the telephone, a seemingly mundane device, could become a "gateway" to virtual adventures which spanned the globe.

Lapsley reiterates to me his belief that this inquisitiveness is a fundamental and valuable part of humanity -- especially for a humanity which day by day absorbs more and more complex machinery for granted, placing it into the background noise of life.

Phone phreaks chose to listen to that noise before spitting oddly sequenced bleeps and tones back at it, "exploding" the quotidian simplicity of the telephone. The aftermath of that explosion has been absorbed into contemporary hacker culture as inspiration, as analogue, even as myth.

We in the mainstream, who are never inclined to unravel the infrastructure which surrounds us, will forever miss the thrill of the hack, the companionship of phreaks and the lost magic of 2,600 Hz.