H2 2017: Something old, something new, something revisited

As we head towards the second half of 2017 and the one-year anniversary of the UK referendum on EU membership, many themes which have pre-occupied financial markets in the past 12 months are likely to continue dominating headlines.

These include Donald Trump’s US presidency and its longevity, merits and scope for tax reforms and infrastructural spending, Brexit negotiations which officially started on 19th June and the resilience of the ongoing recovery in global GDP growth.

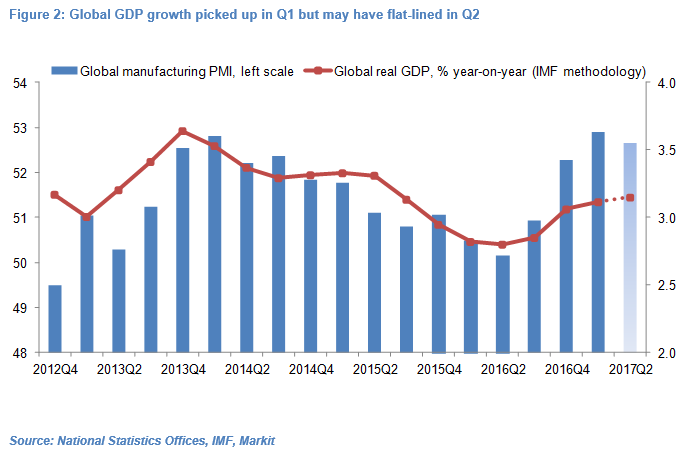

Global GDP growth rose modestly in Q1 2017 to around 3.12% year-on-year from 3.06% in Q4 2016 and a multi-year low of 2.8% yoy in Q2 2016, according to my estimates.

But the global manufacturing PMI averaged 52.7 in April-May, down slightly from 52.9 in Q1 2017, suggesting global GDP growth may not have accelerated further in Q2. This could in turn, at the margin, delay or temper policy rate hikes and/or unwinding of QE programs.

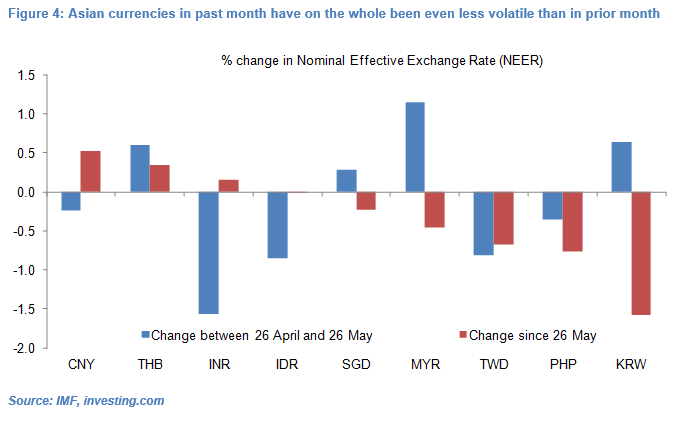

Non-Japan Asian currencies have in the past month been even more stable than in the preceding month, in line with my expectations, but a more pronounced policy change – particularly in China – remains a possibility.

Other themes, such as the timing and magnitude of higher policy rates in developed economies and falling international oil prices, have recently come into clearer focus and will likely be of central importance in H2.

For the UK, I am sticking to my view that a 25bp policy rate hike this year is still a low probability event and I see little chance of an August hike.

The uncertainty over the MPC’s interest rate path and the government’s stance on Brexit complicate any forecast of Sterling near and medium-term but I continue to see the risks biased towards further depreciation.

In France, the hype surrounding Emmanuel Macron’s presidential and legislative election victories is already giving way to whether, when and how smoothly the LREM-MoDem rainbow government can push through its reformist agenda.

Finally, while most European elections are now thankfully behind us, European financial markets are likely to attach great importance to the outcome of Germany’s general election on 24th September.

Conversely, the burning topic of rising European nationalism and future of the eurozone/EU has lost traction following recent presidential and/or legislative elections in France, the UK, Netherlands and Austria.

Second half will see old challenges fade while new one rear their heads

As we head towards the mid-point of 2017 and the one-year anniversary of the UK referendum on EU membership, many themes which have pre-occupied financial markets in the past 12 months are likely to continue dominating headlines.

These include Donald Trump’s US presidency and its longevity, merits and scope for tax reforms and infrastructural spending, Brexit negotiations which officially started on 19th June and the resilience of the ongoing recovery in global GDP growth. Non-Japan Asian currencies have in the past month been even more stable than in the preceding month, in line with my expectations, but a more pronounced policy change – particularly in China – remains a possibility.

Other themes, such as the timing and magnitude of higher policy rates in developed economies and falling international oil prices, have recently come into clearer focus and will likely be of central importance in H2.

Moreover, in France, the hype surrounding Emmanuel Macron’s presidential and legislative election victories is already giving way to whether, when and how smoothly the LREM-MoDem rainbow government can push through its reformist agenda. Finally, while most European elections are now thankfully behind us, European financial markets are likely to attach great importance to the outcome of Germany’s general election on 24th September.

Conversely, the burning topic of rising European nationalism and future of the eurozone/EU has lost traction following recent presidential and/or legislative elections in France, the UK, Netherlands and Austria.

Developed central banks interest rate policy – Incremental hawkishness

Central banks in the US, UK, Eurozone and Canada have become more hawkish in recent months, albeit to clearly different degrees.

US – Two hikes in the bag but appetite for a third let alone fourth hike this year likely to be tested

The US Federal Reserve has hiked its policy rate 50bp year-to-date but markets, which are pricing only 11bp of hikes for the remainder of the year, are clearly divided as to whether FOMC members will stick to their end-2016 forecast that three hikes would be appropriate in 2017. My core scenario is that the Fed will not hike rates again in 2017 although this is not a high conviction call which I will revisit shortly.

UK – A hawkish surprise but still high hurdle for actual rate hike

The UK rates market – dormant since the Bank of England (BoE) MPC cut its policy rate 25bp last August – has sprung to the life after three out of eight MPC members voted in favour of a hike at the 15th June meeting and MPC member Andrew Haldane (who voted for unchanged rates) talked up the possibility of a summer hike. Markets are now pricing 14bp of rate hikes by end-year, with some analysts expecting the MPC to pull the trigger at its next meeting on 3rd August.

I am sticking to my view, expressed in GBP – Hawkish Surprise Presents Selling Opportunity (15 June 2017), that a 25bp rate hike this year is still a low probability event and I see little chance of a hike as early as August. The thrust of my argument is that the economy is still soft and the MPC does not have a quorum in favour of a hike. This view was arguably reinforced by Governor Mark Carney’s re-scheduled Mansion House Speech on 20th June which made very clear that he sees no justification for a rate hike near-term.

One of the three MPC members who dissented in June – Kristin Forbes – will step down from the MPC before the August meeting (her three-year term has expired) and will be replaced by LSE Economics Professor Silvana Tenreyro. While her monetary policy view is unknown, she has been a vocal opponent to Brexit. Historically, new MPC members have tended to vote along with the consensus view and not voted against BoE governors. For example, it took MPC member Michael Saunders – whose first policy meeting was in September 2016 – nine meetings before he dissented in favour of a hike.

It is therefore conceivable that the August policy meeting will see six members voting for unchanged rates and two members (Ian McCafferty and Michael Saunders) voting for a 25bp hike, which markets would interpret as a dovish retreat, in my view. If Haldane votes for a hike, this would yield a five versus three outcome – i.e. no different from the June meeting. Even if a fourth member dissented in favour of a hike, this would lead to split vote. Assuming that Governor Mark Carney, who has the casting vote, continues to vote for no change then the policy rate would remain on hold.

Put differently, there are two scenarios in which the MPC would hikes rates and I think both are unlikely near-term:

- Haldane (or another MPC member) and Governor Carney vote along with McCafferty and Saunders in favour of a hike (and in this four vs four split Carney’s vote effectively counts as two); or

- Carney votes for no change but Haldane and at least two other members join McCafferty and Saunders in favour of a hike.

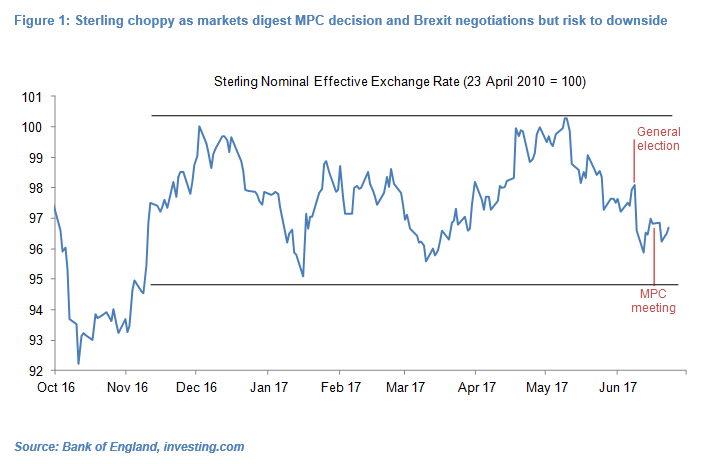

Sterling has weakened about 0.5% and 0.2% respectively versus the Euro and US Dollar since my research note on 15th in which I argued that the MPC’s hawkish surprised presented an opportunity to sell Sterling. The Sterling Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER) has weakened about 0.3% according to my estimates (see Figure 1). The uncertainty over the MPC’s interest rate path and the government’s stance on Brexit complicate any forecast of Sterling near and medium-term but I continue to see the risks biased towards further depreciation.

Global growth rose further in Q1 2017 but signs that it stabilised in Q2

The majority of countries have now released final or first/second estimates of Q1 2017 GDP and I estimate, using IMF purchasing-power-parity weights, that GDP growth rose modestly in Q1 2017 to around 3.12% year-on-year from 3.06% in Q4 2016 and a multi-year low of 2.8% yoy in Q2 2016 (see Figure 2).

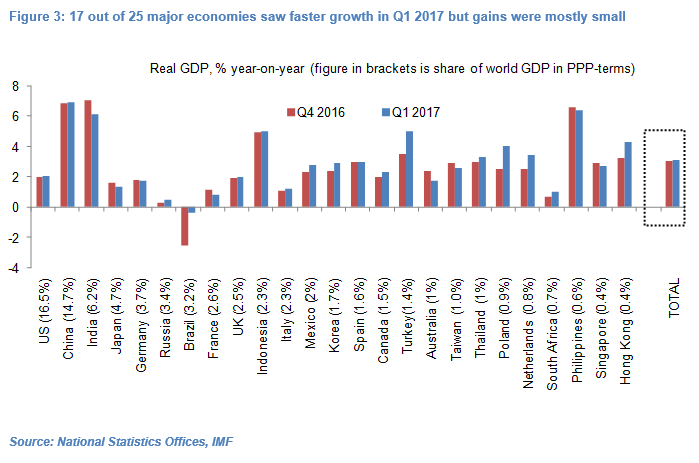

Seventeen of the world’s 25 largest economies recorded faster year-on-year growth in the quarter, although the gains were modest in the US and China (see Figure 3). Still very low global real policy rates are seemingly still helping drive albeit modest gains in global growth while political uncertainty, including in the US, UK, mainland Europe, South Korea and Brazil, has it would seem so far not caused material damage.

The global manufacturing PMI, which has historically been well correlated with global GDP growth, averaged 52.7 in April-May, down slightly from 52.9 in Q1 2017 which suggests that global GDP growth may have struggled to accelerate further in Q2 (see Figure 2). June 2017 PMI data will be released in early July. The IMF, US Federal Reserve, ECB and other major central banks have generally been reasonably upbeat about the global macro picture but signs that GDP growth may be stabilising could, at the margin, delay or temper policy rate hikes and/or unwinding of QE programs (in the US and eurozone).

Asian currencies still broadly on the straight-and-narrow

Non-Japan Asian (NJA) currencies experienced only modest moves in the month to 26th May. Bar the Malaysian Ringgit (MYR) NEER which appreciated about 1.1% and the Indian Rupee (INR) NEER which fell about 1.7%, NJA NEERs appreciated or depreciated by less than 1%. The question was whether this relative calm in NJA currency markets would likely become more entrenched or whether FX flows and/or central bank policy would likely fuel greater volatility or see some currencies adopt a clearer direction.

I concluded that, at this juncture, few central banks – including the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and People’s Bank of China (PBoC) – faced overwhelming economic reasons to markedly alter their currencies’ paths via FX intervention and/or interest rate policy. There was however perhaps a case for Bank Negara Malaysia to favour a weaker or at least stable Ringgit NEER which had appreciated about 2.7% since mid-April (see Asian currencies keeping their head in a world losing its own, 26 May 2017).

This forecast has proved broadly accurate. Of the nine major NJA currencies, six have experienced even smaller changes in their NEERs in the past month than they had done in the prior month (see Figure 4). In particular, the INR, Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) and Singapore Dollar (SGD) have been broadly unchanged. The MYR NEER has weakened 0.5% following a 1.1% gain.

Only three currencies – the Chinese Renminbi (CNY), Philippines Peso (PHP) and Korean Won (KRW) – have experienced grater moves but only the KRW has been truly volatile with a 1.5% fall following a 0.6% rally.

European nationalist parties on back foot but acute challenges ahead for new governments

The recent general elections in France and UK have further dispelled the notion, which gained much traction in 2015-2016, that European nationalist and/or populist parties enjoy great momentum, will reach the highest echelons of power and are on the verge of ultimately shaping the future of the eurozone and EU. The receding threat to the future of the EU and/or eurozone is undoubtedly a source of support for the euro, in my view (see GBP – Hawkish Surprise Presents Selling Opportunity, 15 June 2017).

There is little doubt that in Europe the political, economic and social status-quo is being tested, that nationalism has been on the ascendancy, and that nationalist/populist parties have had greater influence on the political landscape than in the past. However, presidential and/or legislative elections in France, the UK, Netherlands and Austria in the past six months support my long-held view that European nationalist parties are still falling short, failing to cause widely-forecast major political upsets and will in most cases fail to reach the highest political echelons or exercise true power, let alone dismantle the eurozone and/or EU (see Nationalism, French presidential elections and the euro, 18 November 2016, and Black swans and white doves, 8 December 2016).),

France – Bitter sweet victories for President Macron and his rainbow government

President Emmanuel Macron has re-written the rules of French politics. He comprehensively beat National Front leader Marine Le Pen by two votes to one in the second round of the presidential elections on 7th May to become France’s youngest ever president and the first centrist president since Valéry Giscard d’Estaing in 1974 (see 2017 French elections – They think it’s all over…it isn’t, 11 May 2017). Marine Le Pen’s share of the vote was the second lowest ever percentage won by the runner-up in a French presidential election and below the 43% historical average.

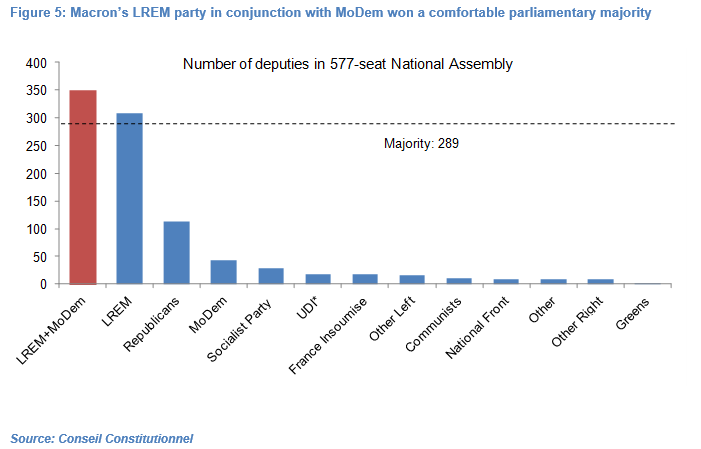

In legislative elections held on 11th and 18th June, La République en Marche (LREM), a centrist party which Macron started from scratch only 14 months ago, won 308 seats in the 577-seat National Assembly – an absolute majority of 19 seats (see Figure 5).

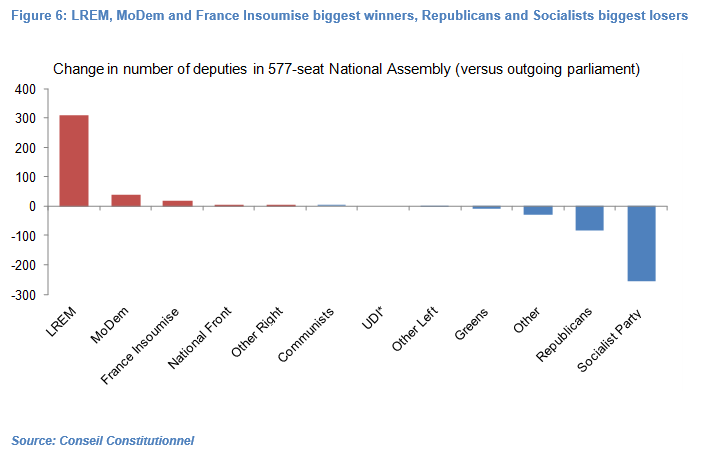

In the process, LREM crushed the heavyweight centre-left Socialist Party and centre-right Republican Party which lost respectively 255 and 83 seats – by far their worst performances under the Fifth Republic (see Figures 6 and 7). The centrist MoDem party led by veteran politician Francois Bayrou – which had only 2 seats in the outgoing parliament – is now the third largest party with 42 seats. As a result, the LREM-MoDem ruling coalition has 350 seats, comfortably above the absolute majority of 289 seats.

Importantly, the strongly pro-EU Macron and LREM have also consigned the anti-EU National Front to the back-pages of French politics. The National Front came third with 8.8% of the national vote but won only 1.4% of the total seats. So while it maintains a loyal following, Marine Le Pen’s party only managed to increase its seats from two to eight and remains a fringe party within the National Assembly.

Macron’s rainbow government and party have captured the imagination, both at home and abroad, and Macron has so far been impressive in his dealings with foreign leaders, including US President Donald Trump and German Chancellor Merkel.

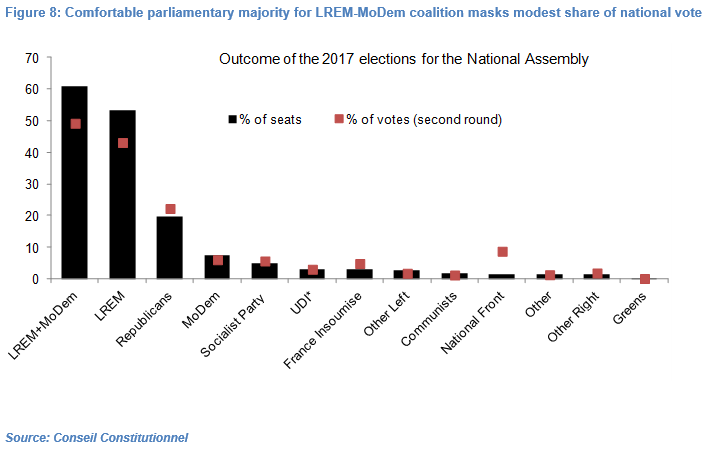

However, Macron and LREM have failed to win the hearts and minds of a majority of the French electorate which will likely become apparent when the government tables unpopular reforms. For starters, the LREM-MoDem coalition fell well short of opinion polls which had predicted that it would win between 400 and 450 seats. More importantly, LREM-MoDem won only 49% of the national vote in the second round on 18th June, which thanks to the hybrid first-past-the-post electoral system translated into 60.7% of the seats [1] (See Figure 8).

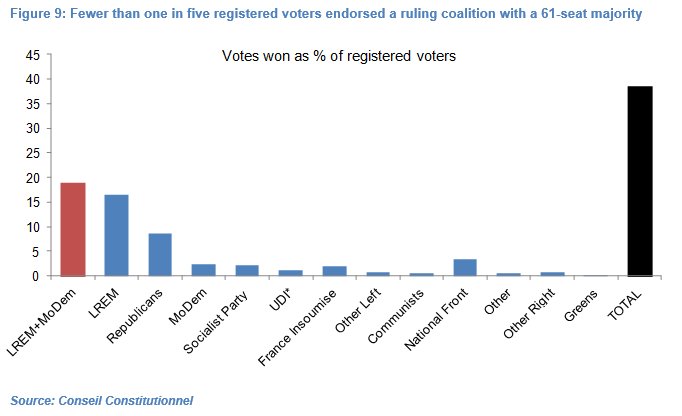

Moreover, voter turnout was the lowest ever under the Fifth Republic with only 38.4% of registered voters casting a valid vote (42.6% voted but 10% of votes cast were blank or null and void). In effect, only 16.5% and 2.3%, respectively, of the registered electorate voted for LREM and MoDem (see Figure 9).

So fewer than one in five registered voters endorsed a ruling coalition with a 61-seat majority. In comparison, in the 8th June British general election, 29% of registered British voters voted for the ruling Conservative party which was deemed to have performed very poorly (see UK Election: Clutching Defeat from the Jaws of Victory, 9 June 2017).

Recall that in the first round of the French presidential elections on 23rd April, which was contested by 11 candidates and was the closest ever, Macron came first with a below-historical-average 23.75% of valid votes and an even smaller 18.2% of registered voters (see 7 reasons why Macron will become president and market implications, 25 April 2017). It is no coincidence that this ratio of 18.2% is very similar to the ratio of registered voters which voted for LREM in the second round of the French legislative election (16.5%). Even in the second round of the presidential elections, which pitted Macron and National Front leader Marine Le Pen, only 43.6% of registered voters gave their support to Macron as a result of a very low turnout and a high incidence of blank or void ballot papers (see 2017 French elections – they think it’s all over…it isn’t, 11 May 2017).

Macron’s honeymoon period is over and he has already had to deal with four ministerial resignations in short successions. A more flexible labour market and significant personnel cuts in a bloated bureaucracy are at the top of Macron’s agenda. Parliamentary approval should not be a problem given the ruling coalition’s large majority but history suggests that winning over an electorate resistant to changes which threaten social benefits will be a far greater challenge. Mass protests and strikes, a common feature in France, may well resurface over the summer.

UK elections have watered down nationalist rhetoric but Brexit still likely to happen

The outcome of the 8th June election for the 650-seat House of Commons suggests that the needle has moved towards a more conciliatory stance with regards to the modalities of any new UK-EU deal. The election was clearly more than just a pseudo-vote on Brexit but UK relations with the EU, along with taxation, public services and domestic security, were undoubtedly a key battleground.

Only 52% of the electorate (and 37.5% of registered voters) voted for Brexit in the 23rd June referendum and perhaps unsurprisingly the ruling Conservative Party, which has consistently pushed for the UK’s exit from the EU, won only 44% of the national vote and lost 13 seats and its parliamentary majorities. Moreover, the pro-EU Scottish National Party (SNP) which has continued to push for Scottish independence won only 3% of the vote (versus 4.7% in 2015) and lost more than a third of its 54 seats, a clear sign of Scottish nationalism in retreat.

But the most telling marker in my view that nationalism took a step back is that the United Kingdom Party (UKIP), arguably the most ardent nationalist, pro-Brexit and anti-immigration party in the UK, saw its share of the national vote collapse from 12.6% (in 2015) to a mere 1.8%. It failed to win a single seat and for all intents and purposes UKIP has for now at least become a footnote in the UK’s political history.

This comes hot on the heels of a number of key elections in Italy, Netherlands and Austria where nationalist and/or populist parties have under-performed (relative to expectations) and fallen well short of being the largest party or even of having major sway over domestic policy. Moreover, opinion polls suggest that German Chancellor Merkel, who championed a policy of admitting millions of refugees, is on course to win a record fourth term in general elections scheduled for 24th September.

Olivier Desbarres

Olivier Desbarres currently works as an independent commentator on G10 and Emerging Markets. He has over 15 years’ experience with two of the world’s largest investment banks as an emerging markets economist, rates and currency strategist.

[1] To be exact LREM won 44% of the votes in the second round and 306 seats (53.2% of total) – LREM had already won 2 seats in the first round of voting on 11th June.