The Brown Revolution: Increasing Agricultural Productivity Naturally

A team of ranchers in South Dakota are using holistic management techniques to regenerate our ailing grasslands and fight climate change

Dusk in Western South Dakota. A half-hour ago, at sunset, the world here made its last pulse for the day: birds hurried between fence posts, mosquitoes emerged from the shadows and feasted furiously, the sweet clover turned iridescent yellow in the late light. Now, the movement has ceased. Even by day it is a quiet landscape, inhabited primarily by meadowlarks and grasses. But as night draws its blue self over this place, the silence is profound.

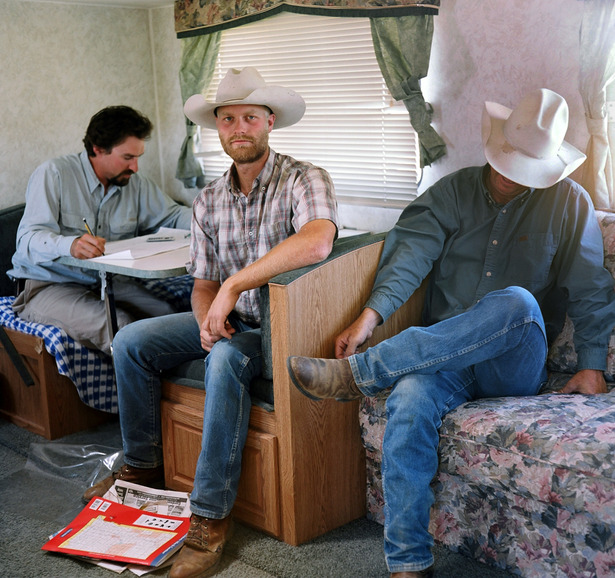

On this particular 8,000-acre section of the Plains there is a single light in view, coming from inside a trailer. Bustling about camp are three men -- cowboys, you'd probably call them. They certainly look the part, dressed in boots and wide-brimmed hats, one of them splitting old fence posts with an axe to build a campfire, another working on some beef for dinner. They call this pasture Horse Creek for the water running down its center, and on it they have 1,100 yearling cattle.

And yet, for these men the bovines are only a means to a greater end. According to the unofficial ringleader, Jim Howell, their goal is nothing less than helping the world to avert a looming global catastrophe. What they're doing here is not just herding cattle; they are starting what they call "The Brown Revolution."

Howell is not revolutionary looking, being of medium height and middle age, with gray spun into his short, blond hair and a bit of John Denver in his face. Back home in southwest Colorado he runs cattle on land that his family has ranched since the 1880s, but over the years he has worked with cattle from New Mexico to New Zealand. He thinks about the world in a vast way, and articulates his globally-minded perspective with clarity and depth, even when sitting by a campfire.

He is the first to offer that the name the Brown Revolution has its drawbacks, foremost of which is that for many it calls to mind a movement based on dung. (Full of conviction, he wonders optimistically if that will spur people to seek more information.) The name is a modern spin on the Green Revolution of the mid-twentieth century. The Green Revolution greatly increased agricultural productivity in developing countries to meet the demands of a growing world population, then one of the world's great challenges; Howell and his group aim to increase agricultural productivity around the world as a way of addressing one of the great challenges of our time, climate change. But while the Green Revolution hinged on implementing new technology, the Brown Revolution relies on restoring natural systems.

The underlying technique is called holistic management, and was developed by biologist Allan Savory in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) beginning in the 1960s. He saw that the arid grasslands on which the region's people, livestock, and wildlife depended were succumbing to desertification. In looking for a solution, Savory recognized that the grasslands had evolved out of a symbiotic relationship with large, grazing herbivores. In time he saw that the same was true of similar ecosystems around the world, including that of western South Dakota and the rest of the Great Plains, with its once-great herds of bison.

In arid environments, plant matter doesn't degrade easily on its own -- it needs these large animals to break it down in their rumens and stamp it into the ground and generally work the land. This was accomplished naturally: As the herbivores traveled in large herds for safety against their predators, they would cause a great disturbance to the land; then, for their own sake, they would leave and not return until the plants had had enough rest to regenerate.

Now take away the Great Plains' bison, or the equivalent animals elsewhere, and replace them with cattle, property lines, and fences. The equation still includes large, grazing herbivores, but because they are relatively stationary within the landscape, the symbiosis is lost. Certain areas are overused, and elsewhere plants simply oxidize and die off from under-use; microorganisms decline, water cycles fall apart, and the land gradually collapses.

The basic premise of holistic management is to use livestock like wild animals. But whereas bison on the Great Plains moved through the landscape by instinct, now ranchers must supply that direction. Rather than simply turning cattle into a pasture, these ranchers conduct them like a herd, concentrating bodies to graze one area hard, then leaving it until the plants have regenerated. The effect can be tremendous, with benefits including increased organic matter in the soil, rejuvenation of microorganisms, and restoration of water cycles.

According to Howell and his colleagues, there can also be an exponential increase in the land's ability to sequester carbon. Savory explains in his paper "A Global Strategy for Addressing Global Climate Change" that there are already 12 million hectares (29.7 million acres) of rangeland managed holistically in Australia, Africa, and North America. Increasing those soils' organic matter by one percent would remove 3.6 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) from the atmosphere. (For context, he offers that "the annual total emissions from all sources for the year 2000 was an estimated 44 gigatons.") Savory goes on to argue that increasing the organic matter by just 0.5 percent across all of the world's 4.9 billion hectares of rangeland would sequester 720 gigatons of CO2e; increasing it by two percent would sequester 2,880 gigatons. In a nutshell, the Brown Revolution consists of sequestering massive amounts of carbon by bringing holistic management to the world's arid grasslands.

"It has to be done on a freaking massive scale," Howell says, "so it's going to require huge flows of capital to make it work. We're not going to own the whole world, but hopefully we're going to be a significant player at the table and influence land management policy on a global scale."

Howell's goal is two-fold: to implement holistic management on enough land as to have an impact on climate change, but also to provide a model that becomes the standard for grasslands management around the world. And he and his team intend to go big, fast. More than once, Howell and his partners referred to the Gates Foundation as an example of the level of influence they hope to wield in coming years.

For now they have partnered with a handful of alternative-minded investors who are fronting the money to buy land that Howell and his crew then manage and transform; Horse Creek's 8,000 acres are less than one percent of what they hope to buy in the Western Plains over the next three years. In the long run, they imagine a publicly-traded entity with shares available to even $10-investors. Because Howell feels so confident in the power of holistic management, his predominant attitude is that more or less all that lies between here and there is just buying the land and making it happen.

"If we have real numbers at scale, if we are generating real numbers in terms of returns on investment that are competitive," he says, his voice rising like a venture capitalist selling a dream deal, "we have this great store of capital out here in the form of land that's not going to evaporate, and we're producing healthy food, and our biological monitoring transects are showing that our species diversity is increasing, and we're covering our soil -- our assumption is that a lot of people are going to want to invest in that."

But that is the future. Right now, dinner is coming out of the trailer and being dished onto blue tin plates. Howell and his partners settle in around the blazing pile of fence posts and begin devouring their beef and noodles like any other group of cattlemen at the end of a long day. As they eat, the conversation turns less global, more local, to area ranchers and the cattle industry of the western Plains.

Listening to them, I'm struck by an odd contrast: It seems that for them addressing climate change is relatively cut and dry -- a challenge, for sure, but one with a strategy to match. More vexing is the question of how to engage and inspire the surrounding community in their efforts. It is essential, for in their minds one cannot fix a landscape that has collapsed without also fixing the community that has collapsed alongside it. But how to do that? That is perhaps the greatest challenge they face.

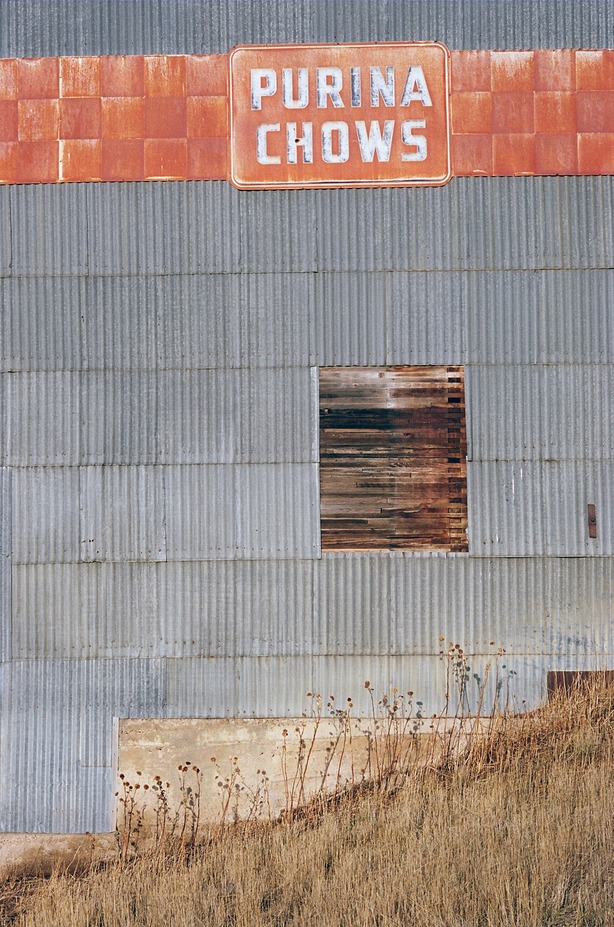

The nearest town to Horse Creek is Newell, South Dakota, ten miles southeast. According to a weathered sign greeting visitors, it is the "Nation's Sheep Capital," but judging from appearances, even the town's purported fame has not saved it from the decline that is epidemic in rural communities of the western Plains.

Downtown is a quiet stretch of respectable old buildings, roughly half of which are unoccupied. No more doctor's office or pharmacy, no more lumberyard or variety store. It is not without commerce: There is still a grocery, as well as a ranch supply store and a meat locker. As in many small communities in South Dakota, there is a municipal bar and packaged liquor store, run by the town for desperately needed income. There is even a gift shop/vitamin outlet/jewelry store/ice cream counter as well as a hotel/fitness center/café around the corner, though it must be noted that when you ring the bell at the former you will be helped, after a brief wait, by the same woman who would help you at the latter. (Rarely does this cause a problem -- business is slow at the café, and the fitness center goes largely unused.)

At its peak in the mid-20th century, Newell had roughly 1,000 residents. These days a sign at town limits announces 675, although that is wistfully outdated; the most recent census numbers show the population to be 603. The causes for contraction are a familiar mish-mash of seemingly intractable problems. Farms got bigger. Agriculture needed fewer people. People started shopping at chain stores in nearby Sturgis. The 1980s farm crisis bankrupted a number of area farms. The drought of the last decade wiped out some more. And on top of all that, Newell has become a town of grandparents. With more than 30 percent of town over sixty years old, death will soon thin the numbers even more.

Despite all this, many locals perceive Newell as being in better shape than an outsider might guess. Yes, downtown is sluggish compared to its previous self, but the community has a secret weapon: water.

Throughout the western Plains, water is the difference between slow, inevitable death and the possibility of survival, and yet its availability is largely a whim of nature and luck of geography. As one local farmer put it, "This country revolves around water: When you've got a lot of it, everything's good and easy. When you don't have it, everything's a lot tougher."

From the beginning, Newell has been an attempt to defy that reality. While there were several small communities in the area at the turn of the century, Newell itself did not exist until the federal government created it in 1904. That was the year the Bureau of Reclamation officially approved plans for the Belle Fourche Irrigation Project, which would convey, store, and deliver water from the Belle Fourche River (whose origin is in neighboring Wyoming) to the farmland around Newell. The project's centerpiece was, for years, the largest earthen dam in the world.

Newell was created as a population center for what would become the newly fertile and booming agricultural region. Originally it was thought that the municipality would be called "Craig" after an area banker, but instead it took its name from Frederick Haynes Newell, a New Englander who was the chief engineer for the Bureau of Reclamation. Water has always been at the core of the town's identity. For as long as it lasted, the local newspaper was called the Valley Irrigator. To this day, the high school sports teams are not the Cougars or the Broncos; they are the Irrigators.

In its heyday in the mid-20th century, the area had a robust agricultural industry built on crops like sugar beets, cucumbers, and dairy -- all of which would be commercially impossible without imported water. Those products rippled out to create other economic opportunities: Both Newell and nearby Nisland had pickling plants among the biggest in the United States; the USDA had a large experimental farm just outside town. And irrigation led to denser settlement than in dryland farming areas, which in turn led to greater social services for the people of Newell, things like multiple schools and medical facilities that were unknown in smaller, dryer towns around the region.

Over time, the other factors that have caused Newell to contract have chipped away at that prosperity, but the water continues to be a source of life that makes the town different from its dying counterparts. That the Irrigation District is headquartered right there in town means a reliable source of jobs and income. More importantly, the project enables irrigation on 57,068 acres of farmland. These days, that land grows mostly alfalfa and corn rather than the high-value specialty crops of yesteryear, but it still makes the land far more profitable on a per-acre basis than the rangeland and dryland wheat surrounding it. Looking at a satellite image of the area in summer, the difference is clear: The land that stretches to the north and east is the dun of dusty old shoes; the pocket around Newell is deep green, the color of money.

Along with the prosperity of irrigation comes an inherent risk, in that the artificial supply carries no guarantee. The reservoir that feeds Newell-area canals has been sloshing full for going on four years now, and yet in the three years preceding, it reached an average of only 44 percent capacity. This ebb and flow is constant, and unpredictable. In 1932, the reservoir reached near capacity, but in 1931 it had "zeroed out" thanks in part to an annual precipitation of less than nine inches, compared to the average seventeen. The 1940s were relatively stable times, but every decade since has held at least one drought year; most have had more. And the future does not look bright: climate models predict decreased precipitation and rising temperatures for the region, which would mean an increased frequency of drought.

Any time the reservoir level sinks, the allocation of water to farmers sinks proportionately. Whereas in a normal year farmers might receive twenty inches of water, if the reservoir is at 50 percent, they will receive only ten. Less water translates directly into less land planted or a smaller harvest. And yet it's not the irrigating farmers who suffer most. Because of scarcity, prices for irrigated hay and feed go up; at the same time, prime customers -- the dryland farmers and ranchers who rely exclusively on rain and wells -- become even more dependent on purchased feed. For irrigators, drought years can actually be a boon.

For the rest, though, drought years can be crippling. Unable to pay the high price of supplemental feed, ranchers are often forced to sell off their herds. As many of them do this, the market becomes glutted and prices drop. Amidst the vicious cycle that ensues, bankruptcy is not uncommon. One local rancher recalled the sell-off that took place during the drought that stretched from 2004 to 2007: "You couldn't even sell them to be butchered," he said. "If you wanted to sell them [to the slaughterhouse] you had to wait four months -- and feed them while you waited. These are the things that pluck businesses and families out of the economy, and out of the community."

Linda Velder, an energetic history buff who runs the Newell Museum, explains that, with every drought, these on-farm losses have rippled out into the community. Less tax revenue from ranches has meant less money for schools, and so fewer extra-curricular activities, shortened classes, lower wages for teachers -- at times local schools have even struggled to pay their electric and water bills. With the ranching community spending less money, stores in town have reduced their inventory and hired fewer people. Some businesses have let their customers buy on credit, but in extended droughts that has led to the stores themselves closing down. Likewise, banks, unable to collect on loans, have shuttered their doors.

All this is to say that while the town is fortified by imported water, it is not invincible. Even the miracle oasis of the Belle Fourche Irrigation Project cannot fully protect Newell from the reality that it exists in a dry land, a place where survival is never guaranteed. In the introduction to his 1969 book, The Sound of Mountain Water, Wallace Stegner laid bare the Sisyphean reality behind projects like that in Newell and throughout the arid West. "Not all the irrigation works of the next century ... can affect the absolute amount of water that the mountains can produce," he wrote, "nor alter the climate sufficiently to take the dry clarity from the air or change the gray and tawny country to a green one."

The Brown Revolution's sexiest element is sequestering carbon on a global scale -- that is what gets people talking. But that is possible only when there are people who are able and willing to do the work of transforming the landscape. Therein lies the revolution's more humble, perhaps trickier goal: figuring out how to create stable, dynamic communities in these arid regions, where the capacity to support human life is limited.

For Jim Howell and company the solution lies in having more water. But rather than import it from elsewhere, their method is to make more of what's naturally available. The person who demonstrated to me how it works is Brandon Dalton, the youngest of the crew at Horse Creek. Blond, scruffy, and six-foot-four, he looks to have walked out of a Garth Brooks video. In truth, he's a wildlife biologist trained at the University of Washington who came to ranching through his wife's family. At Horse Creek he is respected as an expert on wildlife, but as the Brown Revolution's first employee, Dalton is known more practically as the guy who lives part-time in the trailer and is charged with moving cattle and fences from one place to another.

To explain the water cycle, Dalton took me to the creek itself, which by that day in mid-July was not a flowing stream but rather a chain of wet spots marking the vein of moisture that runs down the property's center. Within sight of one another were both the problem and one possible solution. The first was a shallow pothole filled with green grass and holding a couple of inches of murky water, the second a twisting line of water flowing deep in the ground between banks three-feet high. The latter looked more like a creek in the traditional sense, but it was in fact the issue that needed correcting.

Dalton jumped across the mini chasm between the banks and explained that in this formation, the water runs through fast. A heavy rain will bring heavy moisture for only as long as it takes to flow from one end of the property to the other; what's more, it will carve the creek deeper, so that the next rain will flow through even faster. The erosion also lowers the floor of the creek, which in turn lowers the elevation of the water running through it and thus the water table. He showed me how above, on the creek's banks, the soil had dried out and the plants were thin and sparse.

"You can basically see the land falling apart," Dalton said. He kicked the bank and a chunk of soil broke off into the water.

In the pothole, however, the moisture would spread out laterally and raise the water table in a swath beyond its discernible edges. Simply put, rather than running off the land, the water stays there, and the grasses and other plants in that area are sub-irrigated naturally. This matters in any year, but in times of drought it can be the difference between having grass for cattle to eat and having to rely on expensive feed from outside -- the difference between staying afloat and going out of business.

Dalton explained that the gully version of this creek results from too little of the animal impact that was inherent in the self-herding of bison: as the land is over-rested, root systems fail to hold the soil in place, allowing the great force of spring rains to turn naturally gentle depressions into sharp banks. He went on, explaining that this damage can be corrected by the bison-like herding of cattle: Heavy stepping of hooves smooth out steep banks, which allows grasses to germinate there, which in turn will hold soil and begin the process of turning the gully back into a pothole.

Already in that first year at Horse Creek they were stocking far more animals than the former owner -- 1,100 yearlings as opposed to the roughly 160 cows and calves of the previous year. The cattleman from whom they got the yearlings was skeptical that the land could support that many, but after visiting their operation he conceded that the pastures grazed early that spring looked as if they hadn't been touched all year; indeed, they were ready to be grazed again. Dalton explained that the land hadn't even been significantly improved yet; the increase was possible simply as a product of following the bison pattern of heavy grazing followed by sufficient rest. This year Howell and company more than doubled the herd to 2,250 head, and the land appeared to be improved even further: greener, and with a greater diversity of grasses and forbs proliferating.

In the long-term, Dalton envisions a water cycle so improved that beavers and other uncommon wildlife might populate this creek. This early in the game there's no telling what will happen, but throughout the holistic management community there are examples of great transformation that inspire fledgling projects like this. One renowned rancher in Wyoming rehabilitated the main creek on his ranch and expanded its riparian area from a width of 30 feet to a half-mile. In six years, he increased his land's productive capacity by 150 percent.

"To the extent that you can gradually make that happen more and more and more," Howell explains around the campfire, "the more biological wealth you have out there that is going to sustain life of all forms, as well as profitability for humans. So at the end of the day, that's totally what it all comes back to. That's why these landscapes have collapsed and people can't make a living off of them anymore and the towns have collapsed: it's because water is evaporating or running off as opposed to soaking into the soil."

The third partner on the ground at Horse Creek is Zachary Jones, a funny-guy type with wild dark hair and a goatee. He raises cattle on a ranch outside Harlowton, Montana, that has been in the family for more than a century, but like his Brown Revolution compatriots, he is noticeably unconventional: He drives a Subaru station wagon instead of a pick-up. He makes kombucha mushroom tea in a vat at home. In the trailer at Horse Creek, he is never far from his MacBook. In the group of three, Jones is the philosopher, the one to introduce a cosmic perspective that reframes a conversation.

As we discuss the practical strategy behind improving the water cycle, he interjects: "But before you get to managing the soil surface," he says, "you have to get to what manages the soil."

Howell picks up his lead. "Right! Which is human beings and their tools. So, at the end of the day, it comes back to that: a shift in what drives our decision-making. Ultimately it's about getting water to soak in, but there's so much that has to happen before that."

That may be the biggest challenge the Brown Revolution will face in South Dakota and elsewhere in the arid West: getting people to change their relationship with the land. The crew at Horse Creek can create a model of what's possible, and even, by buying enough land, have an impact on a larger scale. But the real revolution will come only when this change is made throughout the region by the individual owners who together hold more land than Howell and company ever will.

It comes back to holistic management's premise of emulating the natural ecology of a place. The larger the scale, the better the concept works; ideally it would entail enormous herds of animals moving across entire regions -- for instance, not just Newell but all of the western Dakotas, or the High Plains of Texas and New Mexico. At that magnitude, it would be possible to restore the entire water cycle and not just a section of creek. The obstacle is that it requires a fundamental shift: People must see the land not as a series of individual properties, but as one larger whole.

There is a movement in the Great Plains to reintegrate individual holdings into a single landscape. Called the Buffalo Commons, it would involve landowners selling their land to public ownership in order to create essentially a giant nature preserve. The idea is to establish some semblance of the open, bison-covered plains that existed before Americans cut the range into pieces. There's just one problem: it requires essentially dismantling the community and economy that now exists in the rural areas of the Plains, which, ragged as it may be, is composed of more than three million people.

As Howell and Jones see it, simply deleting people from the picture doesn't solve problems for the long run. "What is necessary is to have competent, rooted, native people who know how to live in these places," Howell says. "Without a skilled human element we can't bring about the ecological shift."

From Howell's perspective, the problems stem not from our presence in this particular landscape but from how we've chosen to act there. Ever since European settlers arrived in the 19th century, the core of the Plains identity has been independence and dig-in-your-boot-heels resilience. It has seemed necessary -- those needing outside help simply don't last in this ruthless environment.

I thought of this as I looked through the Butte County Post one morning. The "Rural Newell News" section told mostly of ladies' luncheons and visits from out-of-town guests, but the first two items read as follows:

Merle Vig of the Mud Butte area got rid of the neck brace. He and a horse had a difference of opinion and the horse won that round.

Don Stomprud had some of his buildings rearranged out at the ranch when the tornado went through his place. He felt that he was lucky that the damage was not worse.

As much as community matters deeply to people who live in places like Newell, their first response to the world's challenges is a sort of radical self-reliance. Therein lies the greatest challenge that Howell and company face in these parts: seeing the landscape as a larger whole requires that people see themselves as part of a larger whole.

I recall explaining the Brown Revolution to a local ranching couple, who seemed cautiously intrigued. But when I suggested that the concept might be accomplished through ranchers forming a cooperative, the wife looked at me askance.

"You mean they'd need to work it as a sort of coalition?" she said.

"Yes."

"That'll never happen."

That was the end of the conversation.

The Horse Creek crew is not yet ready to debate the core Plains identity with the crowd down at the diner in Newell, but privately Howell suggests that perhaps the foundation supporting this immutable independence is faulty. It's thinking made popular by Wallace Stegner, who believed that pioneers heading west over the hundredth meridian brought with them a relationship to the environment shaped by ample rainfall as exists in the Eastern United States and much of Western Europe.

"The history of the West," Stegner wrote, "has been a history of importation of humid-land habits (and carelessness) into a dry land that will not tolerate them; and of the indulgence of an unprecedented personal liberty, an atomic individualism, in a country that experience says can only be successfully tamed and lived in by a high degree of cooperation."

Seated in the trailer at Horse Creek, Howell argues that that misplaced identity is exactly why towns like Newell are collapsing throughout the western Plains. In his view, the entitlement to autonomy that is possible in lands with ample rainfall should be replaced here by a new pattern of settlement guided by what the land is capable of providing.

"When I say that the community needs to be healthy and stable and secure to realize the land's ecological potential, that doesn't necessarily mean salvaging all the little towns," he explains. "Ultimately, that's what's driving us: to create a new culture, a whole new approach to living out here on these landscapes, one that's appropriate to this place. And that's the hardest thing of all, for cultures which are based on habits to change and evolve over time."

Howell and company recognize that such change takes generations, and that they're unlikely to happen here in Newell in the immediate future. So for now they are focused on just implementing their model and growing it as big as they can. At least in terms of expediency, abandoning the immediate pursuit of major social transformation is actually a plus. Not saddled by the collaborative process, they can simply buy land and change its management overnight, bringing improved carbon sequestration that much more quickly.

The drawback is that this approach, too, relies on imported resources -- not mountain water from Wyoming but rather investment capital from New York City.

There's an old joke among cattlemen that the best way to make a small fortune in ranching is to start with a big one. And yet the Brown Revolution's lead investor, the Greenwich, Connecticut-based Capital Institute, is optimistic about their investment specifically because it seems secure in comparison to the current financial market. The strategy is not centered on real estate -- they don't intend to "flip" the land after improving it, the way some housing developers do. They aren't waiting to cash in on carbon credits, either, though that may provide additional income down the road. In time they'd like to expand into producing grass-fed beef for the specialty food market, but for now the model revolves around minimal capital investments and steady returns. Their medium is the humble industry of custom grazing, whereby contractors fatten yearlings on pasture then return them to their owners to sell.

It goes like this: The Brown Revolutionaries buy under-utilized land for cheap, implement holistic management as contractors using other people's cattle, and collect profits in the form of fees for the custom grazing service. As the land improves through their management, they'll be able to accommodate more yearlings and collect more profit.

"If you invest a hard number each year with no capital investments and you can double that over X amount of years, you have a much more stable investment than most," reasoned John Fullerton, the Capital Institute's founder and president. "It's not like buying Google when it was still a private company, but from my vantage point, on a risk-adjusted basis it's actually quite attractive."

There is a precedent for just this sort of profit-oriented speculation from afar, in the cattle barons of the Old West. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, massive herds grazed the open range of western South Dakota. (At the turn of the century, Belle Fourche, 25 miles west of Newell, was the world's premier livestock shipping point, with 2,500 railcar-loads of cattle leaving each day.) Those animals were herded by hired cowboys and owned by investors who mostly lived elsewhere -- often in more humid climes such as New York City and Great Britain. But as fencing and farming changed the circumstances of the West, it became clear that owning cattle was a risky business; savvy investors took their money out of raising meat and put it into processing.

What's to say that the Brown Revolution's funders won't pull out if their investment falters? How will they guard against the folly of humid-land thinking, expecting the land to produce at a desired rate rather than recognizing its ebb and flow? And what if drought returns? Would a few dry years prove the holistic approach, or would it disband the revolution?

It must be said that the investors are not driven solely by dollar signs. Fullerton, for one, believes that such socially responsible investment has meaning beyond money. "Our purpose," he says, "is to demonstrate that there is a way to deploy capital in a way that's aligned with the ecological crisis we're facing, but on the investment side of the line that separates investment and philanthropy. We're not doing this because it's the biggest way to get a return, but I think it's a pretty smart thing to do with my money as opposed to putting it in the stock market."

But is that enough to sustain a revolution? While local ranchers would have their roots to carry them through the ups and downs of a new system, it remains to be seen how long outsiders will hold on through hard times. In her book Dakota: A Spiritual Geography, Kathleen Norris captured the nature of this place and the beings that try to make it their own. "The Plains are not forgiving," she wrote. "Anything that is shallow -- the easy optimism of a homesteader; the false hope that denies geography, climate, history; the tree whose roots don't reach ground water -- will dry up and blow away." If this new vision for western rangelands is to succeed, the commitment of its visiting visionaries -- Fullerton and Howell alike -- must prove deep enough to last until the local community is ready to join the revolution.

Image: Lisa Hamilton.

This article was written with the support of the Alicia Patterson Foundation.