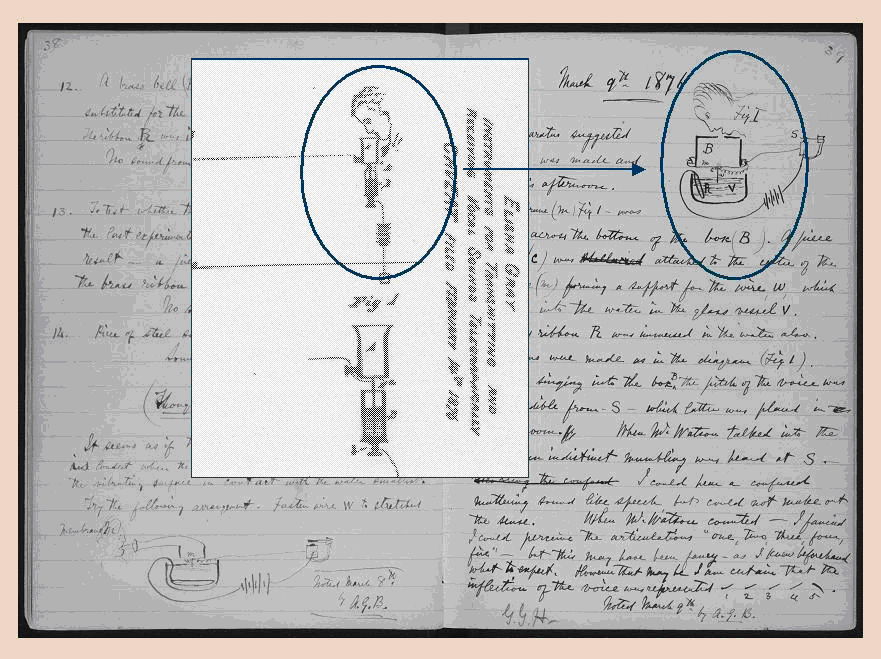

More than three decades after the idea of a telephone was first considered by Innocenzo Manzetti, two Americans rushed to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on February 14, 1876 to claim credit for the world-changing invention. Though others would lay claim to creating devices capable of transmitting the human voice in the years before, the competition between Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray would come to define the 20-year battle to secure control of the technology. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the electrical telegraph rapidly became the primary means to send messages across long distances quickly, particularly after Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail created a code for signalling the alphabet to use with Morse’s own model patented in 1837. Within 30 years, telegraph cables stretched from one end of the United States to the other and across the Atlantic Ocean well into Europe. Far away in France, telegraph company employee Charles Bourseul took Morse’s design and combined it with elements of the system designed by his countryman L. F. Breguet to improve the capabilities of the network he worked on. In September 1854, he published a memo in Parisian magazine L’Illustration and the German periodical Didaskalia describing how an electromagnetic disc that “makes and breaks the currents from a battery” would likely be capable of sending speech “in a more or less distant future.” German Johann Philipp Reis decided to give the idea a try. His “telephon,” featuring a setup similar to Bourseul’s concept and built in 1860, demonstrated the ability to send music and some voices over a distance. Though correctly called the first true telephone, the inability to consistently replicate a sound from one end of the cable to the other — not to mention the poor clarity of spoken words — kept it from being viable as a widely-used device. By the mid-1870s, Illinois-based Gray was piling his energy into the invention of a “harmonic telegraph” capable of sending several messages across the line at once. At roughly the same time, Bell was using his free time to come up with a device for a similar purpose from his office in Boston. Gray succeeded first, showing off the ability to send musical tones at Highland Park First Presbyterian Church in December 1874. More than a year later, Gray scribbled out a loose design for “Instruments for Transmitting and Receiving Vocal Sounds Telegraphically” in his notes. Three days after coming up with the design, on February 14, 1876, his lawyer filed a caveat with the USPTO, in effect stating Gray would be filing an application for a full patent later. An attorney representing Bell hand-delivered a request for a full patent the same day, but without a working prototype for officials to test as required by law at the time. Payment was recorded for Bell’s application first, at least giving the appearance his design took priority over Gray’s, a fact which later led Gray to withdraw his caveat. On February 19th, Bell’s application was put on hold for 90 days to allow Gray to file a full patent request. Five days later, Bell headed to Washington, DC for a period of nearly two weeks. Back in Boston by March 8th, he recorded an experiment in his lab notebook containing a sketch with a striking resemblance to the one submitted in Gray’s caveat. When he noted the successful test of his patent model two days later — “Watson, come here, I want to see you” is written in the journals of both Bell and his assistant, Thomas Watson — the grounds for a future lawsuit were laid, one with twists and turns that lasted for nearly a decade. Bell’s design, using a thin membrane with piece of iron in the middle to interact with a pair of electromagnets, transmitted sound waves produced by a human voice to a similar layout on the opposite end of an electrically-charged wire. When the current reached the receiver, the vibration of the soft disc disrupted air in a way that mimicked speech. By January 1877, Bell had tested a “long distance” transmission (covering 10 miles) and received a patent for an altered design that streamlined the passage of electric current. Voices were difficult to hear, but the ability to distinguish one word from the next was present. In March 1877, Bell wrote to Gray that he had knowledge of the competing design, adding fuel to the fires of contention between the two men. Filings at the USPTO were deemed confidential until testing was complete, meaning Bell must have secured his knowledge illegally. Two years later, Bell said during a court proceeding he talked “in a general way” with a patent examiner about Gray’s design, which allowed him to learn it “had something to do with the vibration of a wire in water.” The man in question, Zenas Fisk Wilber, testified in April 1886 he owed money to Bell’s lawyer Marcellus Bailey and told him of Gray’s caveat. He went on to describe receiving a hundred-dollar payment from Bell after he “explained Gray’s methods to him.” However, due to differences in his original testimony from six months before citing being tricked into signing paperwork while drunk, the affidavits were considered erroneous. In the meantime, Bell Telephone Company rapidly became the primary source for the new technology, fighting through legal challenges until 1896, when the last claimant to the invention — a man from Pennsylvania named Daniel Drawbaugh who purported to have created the telephone with a teacup in 1867 — had his case dismissed by judges. Also On This Day: 1778 – The United States flag is recognized at sea for the first time 1779 – Captain James Cook is killed by Hawaiian natives on his third voyage to the Pacific Ocean 1835 – The first Quorum of the Twelve Apostles from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is formed in Kirtland, Ohio 1929 – The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre occurs in Chicago, Illinois, leaving six rivals of gangster Al Capone dead 1989 – Union Carbide agrees to pay $470 million to the Indian government for the Bhopal disaster of 1984 You may also like : February 14 1929 – The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre occurs in Chicago, Illinois, leaving seven rivals of gangster Al Capone dead February 14, 1912 – Arizona admitted to the Union

February 14 1876 – Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray Apply for Patents on the Telephone

More than three decades after the idea of a telephone was first considered by Innocenzo Manzetti, two Americans rushed to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on February…

450