A whiff of revolution was in the air last weekend: could it be that it was coming from that new low-budget Chinese comedy? But Lost in Thailand, opening in a mere 29 out of America's 5,000 cinemas, was no ordinary Chinese comedy. Dubbed China's answer to The Hangover, the $3m (£1.9m) chancer knocked Life of Pi off China's No 1 spot in December and blindsided several domestic blockbusters on its way to becoming their most successful film ever – homegrown or foreign. Something unspoken lay behind expectant articles in the film press for its US opening: the idea that this could be the point when cinema's trade winds stopped blowing from west to east, and the reverse became possible.

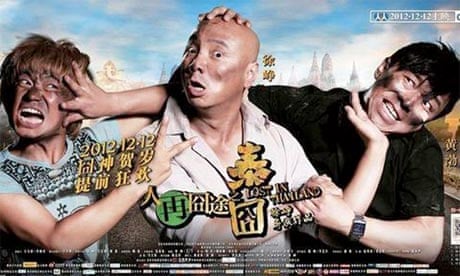

Well, sorry, not quite. Not even Chinese-Americans represented in serious numbers, given this auspicious opportunity; Lost in Thailand took only $29,143 over the weekend (a tepid screen average of $833), to bolster its record-breaking $194m Chinese haul. It's a blow for those interested observers who had noted that this unexpected hit from a minor studio was a very different breed of Sino-blockbuster. It wasn't the normal blowhard historical epic or martial-arts fantasia, but a limber contemporary comedy in which a businessman (Xu Zheng, who also directs) trying to track down his boss in Thailand is waylaid by a Zach Galifianakis-like buffoon (Wang Baoqiang). (Technically, it's more Chinese Due Date than The Hangover.)

Lost in Thailand touched on an open contemporary nerve rarely visible in the country's commercial cinema. It's been praised for speaking directly to the ambitions and anxieties of China's growing urban middle class. "Many of them feel confused and tired and even like they are losing themselves," Beijing university's Zhang Yiwu told the South China Morning Post, "Lost in Thailand is a very good movie for invoking thought and showing the frailty of urban citizens." Invoking thought wasn't something The Hangover, or many of the other mismatched-buddy Hollywood models for Lost in Thailand (the Zheng-Baoqiang partnership was first struck up in 2010's Lost on Journey, apparently inspired by Planes, Trains and Automobiles), were remembered for – but then this style of film is still a novelty for Chinese audiences.

The hope was that this new vein of comedy, and the resulting boost to the industry's self-confidence, would register on the other side of the world; that it would prove Chinese cinema was finally gaining the kind of zeitgeist antennae needed to be truly responsive and commercial. Then the unimaginable – that the country's film-makers would one day challenge Hollywood for global influence – might look plausible. But cinema chain AMC's decision to treat Lost in Thailand as just another niche release means that the new face of Chinese film (if there is one) remains untested in this biggest of arenas. It's possible, of course, that AMC (who acted, unusually as both distributor and exhibitor) made a prudent market call, and Lost in Thailand's humour is simply too Chinese to gain wider sway. That was presumably the case with the entertaining but often baffling 2010 action-comedy Let the Bullets Fly, another former Chinese No 1, which grossed a feeble $69,000 in the States.

The curious twist is that AMC, responsible for over 5,000 screens across North America, are actually Chinese-owned – by Dalian Wanda Group, now the world's largest exhibitor chain. Part of me does wonder if the company's low-key treatment of Lost in Thailand (there was little publicity outside of YouTube and Facebook) is also to do with not being seen as a broadcasting mouthpiece for the Chinese government and its global soft-power ambitions; it's a sensitive time, with many eyes trained on the US and China's diverging fortunes. Whatever the reason for the decision, the marketing muscle to propel Chinese blockbusters will surely materialise at some point in the near-future.

I don't buy the argument that any film is "too culturally [whatever]" to succeed – the east, with China catching up over the last decade, has been lapping up Hollywood and American values for half a century, and there's no innate reason the opposite won't happen. Chinese culture overall might have to start looking a bit more comely first; there might have to be a few more Lost in Thailands to break in western audiences. Perhaps Xu Zheng's comedy needs time to freshen up the Chinese industry internally for those things to happen. Hollywood might have got a reprieve from that particular hangover for a couple more years.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion