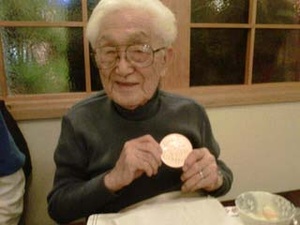

I had the extraordinary experience of getting to know a Nisei solider before he died in 2013. His name was Masao Abe and he was born in 1916. I met Masao when he was in his late 80s and, after his precious wife of 63 years died, spent two days a week with him during the last three years of his life. I came to love Masao, he was like a father to me. He was kind, generous, and had the most wonderful sense of humor. I miss him still.

What I appreciated about Masao more than anything was what he taught me about American history. Before I met Masao, I didn’t have much of an interest in history nor did I understand the significance of certain historical events or periods. How wrong I was to have dismissed what happened before as though it mattered not. History matters now more than ever and the Nisei still living among us will be the first to shout that message loud and clear.

Masao’s story is one of confusion, happenstance, and loyalty. It’s important to get a glimpse into his life because what he, and others like him, endured - paved the way for generations that followed. It seems that the sacrifices the Nisei tolerated have not yet been fully digested by Americans at large. For me, I never understood or appreciated the plight of Japanese-Americans until I met Masao.

A Nisei, he was born in San Bernardino to Issei parents and lived there until he was eight at which time his family took a trip to Japan. Unbeknownst to Masao, the plan was to leave little Masao in Japan upon the family’s return to California. His parents wanted him to have a traditional Japanese education and they believed that could best happen in Japan. Little 8- year-old Masao had to overcome the jeering of his Japanese peers - they called him retarded because, even though he was fully Japanese, he spoke only English.

After some years in Japan living with his paternal grandparents, Masao’s school tracked him to become a soldier. Masao embraced this path and was proud to prepare as a soldier for the Japanese Imperial Army. In the early 1930s, Masao’s family moved from San Bernardino and joined him in Japan. Masao, content to be in training to join the army as a Second Lieutenant once he turned 20, now spoke only Japanese and had forgotten even basic English. But his father, Yasoshichi, had different ideas for Masao. Yasoshichi, having lived in California for years, couldn’t bear the thought of his oldest son in the Japanese military, a military that had a reputation for being brutal and, at times, inhumane. So, at perhaps great peril to the family, Yasoshichi sent Masao out of Japan and back to San Bernardino to live with an uncle just a few months before Masao turned 20.

Back in California, Masao wasn’t sure what his future held. He didn’t know enough English to attend college and his Nisei peers viewed him as Kibei, a term Masao disliked completely. He didn’t fit in, once again, and he missed Japan.

In September 1941, Masao was drafted into the U.S. Army, something that delighted him. Once beyond Boot Camp, Masao was ready to represent the U.S. - his birth country. But then Pearl Harbor was attacked and even though military officials assured Japanese-American soldiers that they would be seen as Americans, Masao realized that he, and other Japanese-American soldiers, were viewed as suspects, if not the enemy.

But Masao persevered and performed his job as a medic at various military facilities state-side. He applied for military positions that would take him into active combat in the European theater, and he hoped that he would, one day, be recognized as a soldier. His applications were rejected one after another until he discovered the Military Intelligence Service, a highly secret operation that began even before Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Masao endured months of training with the MIS, training that included interrogation, interpretation, infantry, and combat. He was shipped out to the South Pacific in 1944. Attached to the 81st Infantry Division, only the highest ranking officers were aware of his presence and purpose and, even then, some of those officers didn’t want any part of the MIS operation. They considered Masao and other MIS soldiers as a problem, a problem that was forced upon them by higher-ups. They didn’t see the value of having interpreters on the front lines, they saw it as an interruption in battle field operations.

Because the Nisei were fighting on the front lines and amongst mostly Caucasian soldiers, bodyguards were attached to the MIS soldiers 24/7. They were indeed a target of the enemy, but were at risk of being the target of friendly fire as well. Masao ended up fighting in three battles including two in the Palau Islands and one in the Philippines. Most days, he believed that he would not make it out alive. He was shot by a sniper on the island of Peleliu and barely survived the ordeal, only to be shipped out again before he was fully recovered.

At the war’s end, Masao had earned enough military points to be honorably discharge but the military overruled the discharge and instead sent him to Japan to serve in the occupation. Returning to Japan in an American uniform was difficult at best. While he was proud of his service with the U.S., he knew he would be met with vitriol in a Japan that was war-torn, economically broken, and desperate.

Masao served the U.S. government in Japan but had a heart for Japanese citizens. He and his army buddies routinely took their ration of cigarettes, whiskey, blankets, and anything else, to share with local Japanese, many times in the worst locations around Tokyo. But it was in Japan where Masao met his wife to be, Doris, a Japanese-Hawaiian who was in Tokyo working as a civil servant.

Thankfully, Masao’s story had a happy ending. But the take-away isn’t the happy ending. The take-away is to comprehend how much pressure was on Masao, certainly from the age of eight until he was a grown man, to adapt to a changing world and a world that, because of his race, wanted him to disappear. Like so many other Japanese-Americans, Masao managed to maintain his dignity and humanity even when treated with indignity and, at times, surrounded by inhumanity.

Today it isn’t Japanese-Americans who are being targeted to disappear, the focus of today has shifted to other groups; Dreamers, Muslim-Americans, and African-American men to name a few. Because of their own experiences with American history and evolution, Nisei voices are often the first ones to be heard in defense of these vulnerable groups being targeted by the government, hate groups, and incendiary talking heads - very similar to what they, themselves, experienced in the 1940s.

When our elders who have lived through the worst, the struggles, the racism, the oppression, and they still have the energy and strength to tell their story - we should listen. We should listen with both ears and our entire heart. Their message and their voice is as important today as it was 75 years ago. Their advocacy reaches out and addresses the struggles of the most vulnerable among us today.

The Nisei who lived through World War II are a vanishing gift. Let’s hear their voices and learn from their wisdom. Let’s listen.

© 2017 Sandra Vea