The Looming Challenges for Obamacare in 2013

How quickly the politics of health care has changed. Just over a month ago, the country was debating whether President Obama's health reform law, aka "Obamacare," should be saved or scrapped. Now, with the president's reelection, that's all settled, and regulators, states, employers, and health care providers are rushing to get ready for a transformed system that is coming in 2014.

This involves several challenging tasks. Industry is readying itself for hundreds of pages of regulations, insurance companies for new products and some 7 million new customers in the first year, states for an IT infrastructure unlike anything they have seen. Employers are facing a raft of new requirements, including an obligation to cover all of their workers or pay fines for not doing so. Congress's role is minuscule. House Speaker John Boehner acknowledged as much days after the election, when he said that Obamacare is "the law of the land" and that repeal efforts were over.

But the lingering uncertainty around the law -- and its expansive ambitions -- means that the work to be done between now and January 2014 is enormous.

Public Education

- Health Exchanges a Tough Sell With Many States

- Will Coverage for Older, Sicker Patients Become a Target for Cuts?

- The 'Contraceptive Mandate' Versus Religious Freedom

Some 50 million people in the United States are without health insurance, and nearly 40 million of them stand to benefit from the law. In states that choose to expand their Medicaid programs, all residents who earn below 133 percent of the federal poverty limit, about $15,000 annually for a single person, can sign up for the federal-state Medicaid program. And in every state, people of moderate income will be eligible for tax credits to help them buy health plans on regulated public marketplaces, called exchanges.

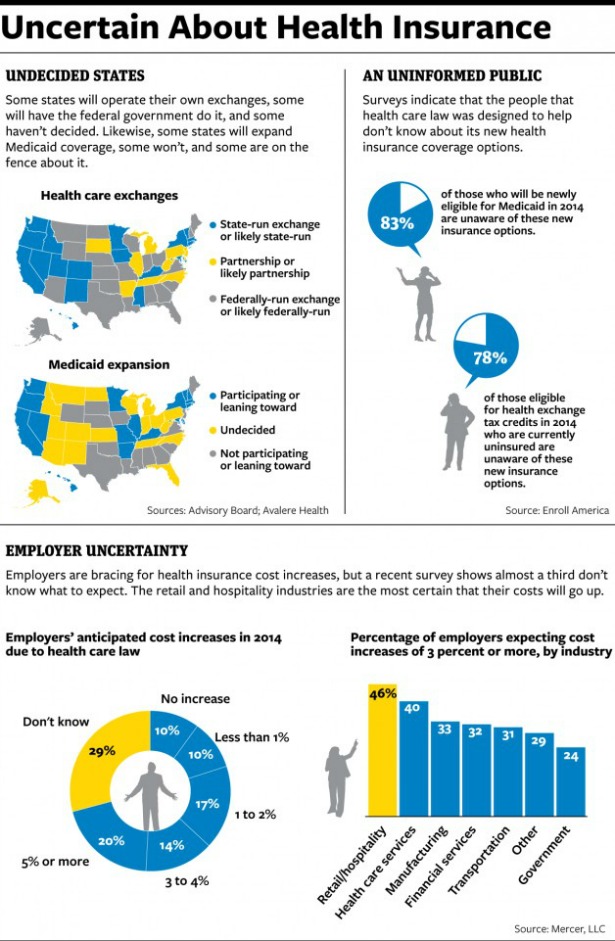

Getting those marketplaces built and the states ready to accept a flood of applications are big challenges. Perhaps a bigger one is reaching all those eligible people and educating them about how they can benefit. Although public polling has shown consistent and strongly held views about the health law overall, public understanding of its individual provisions has always been low. A recent survey conducted by the newly formed Enroll America found that 83 percent of people who will be eligible for Medicaid were unaware of their status, as were 78 percent of those eligible for tax credits.

"I can't think of any task that involved changes in America's health care system over the last half-century that is as big a challenge as reaching these tens of millions of people," said Ron Pollack, the executive director of Families USA, a health-reform advocacy group that has joined forces with the health industry and charitable groups to form Enroll America.

Enroll America is hoping to raise "tens of millions of dollars," according to Executive Director Rachel Klein, money that will be devoted to television and online advertising, as well as word-of-mouth education that can reach the uninsured in their communities. The group, which draws on resources from health insurers, hospitals, and religious and community groups, will conduct a nationwide push, with a greater focus in the states with the largest population of uninsured residents.

Enrollment levels will matter, because the number of Americans the law insures will largely determine whether the Affordable Care Act is considered a success or failure. But enrollment levels will also determine whether the law's basic apparatus will work. The Affordable Care Act is designed to bring young, healthy people into insurance markets, where they can help offset the costs of insuring the old and the sick. Populations that are already in constant contact with the health care system will be encouraged to sign up for insurance as soon as they can. But the healthy people the system will need are the ones who will be hardest to reach. Without their participation, the law may not succeed in making coverage affordable for the uninsured.

The federal government will be involved in the public outreach, and it is developing a strategic plan, built on its enrollment efforts after the enactment of the Children's Health Insurance Program in 1997 and Medicare Part D in 2003. Political considerations, however, might limit the government's efforts. House Republicans have already called for an investigation into the decision to devote government funds to the promotion of the health care law. To critics, such advertising smacks of political advocacy.

The role of states may be more variable. In Massachusetts, the only state to have rolled out a similar system of expanded coverage so far, politicians and the business community pulled together in support of the law, and a clever advertising campaign, linked to the Boston Red Sox, told young, healthy, uninsured residents that they should buy insurance. More than 95 percent of the state's residents are now insured. Several people involved in the effort say that the marketing campaign, and the uniformity of the public message about the law, were key to its success.

But not every state is Massachusetts when it comes to health care reform. "The question is, in Mississippi, do they run those ads, and does somebody from the tea party get on afterwards and say, 'Stick it to the government. Pay a penalty instead.' " said Jonathan Gruber, an MIT economist, who worked on the Massachusetts and federal plans.

A few states have begun their own advertising and public-education campaigns. California, Maryland, and Washington, among others, have already started planning their pushes. Yet many of the states that are resisting the health care law -- refusing to build their own exchanges or to expand their Medicaid programs -- are those with the largest uninsured populations. Those states already tend to have lower-than-average rates of participation in Medicaid by populations that are currently eligible, suggesting either cultural resistance to public assistance or systems that have discouraged enrollment. Those factors suggest greater challenges in bringing uninsured people into the health care system. "There may be unevenness from state to state," Pollack said.

States

Another challenge is creating and supporting the online marketplaces where individuals will find the insurance plans. Nine states have refused to expand their Medicaid systems to cover new populations -- leaving a gaping hole in those states' coverage expansions. About 20 have decided not to help build the state insurance exchanges where individuals will be able to shop for plans. The federal government is planning to intervene in those states and install its own exchanges, but it's clear that uncooperative states will be able to throw a few wrenches into implementation.

When individuals come to seek insurance, they will be interacting with brand-new systems. Aside from Massachusetts, no state has built the kind of regulated online insurance marketplace outlined in the health care law. The idea is for each state to have a website similar to what Kayak is for travel: People will go online, answer a series of standardized questions, and immediately find out what insurance plans they can purchase and what financial assistance they qualify for.

The back-end labor involved in building the necessary IT infrastructure has proven to be tremendous and full of unexpected complexity, say officials in the states that have been working most diligently to create their own exchanges. The exchanges must be able to communicate with a yet-to-be-built federal eligibility database; state-based, often antique, Medicaid computer systems; and the many insurance plans that wish to sell in the market. The vendors building the systems are starting from scratch, and regulations spelling out the precise specifications for data connections are still pending.

Connecticut's exchange plan was conditionally approved by HHS this week, putting it near the head of the pack. Still, Kevin Counihan, CEO of the Connecticut Health Insurance Exchange, said that getting to the finish line in time will be a scramble. "Do I think it's going to be ugly getting there? You bet," he said. "If everything works perfectly, we're fine. But things don't work perfectly in life, and they certainly don't work perfectly in IT development."

In the states that don't want to help, additional challenges are coming. Some parts of the federal apparatus can be identical in every state where it's operating. But the federal exchange will need to be tailored to meet the regulatory and eligibility standards in each state, an effort that could be complicated by recalcitrant state officials. Medicaid systems that cooperate only minimally could undermine the "no wrong door" approach behind the exchange design. Instead of a few clicks separating consumers and health insurance, Medicaid-eligible populations in some states may instead be forwarded to a separate eligibility and enrollment system managed by state officials.

Gary Cohen, the head of insurance oversight at HHS, said this week that the federal government will be ready to do its part in time. It's hard to know, however, because the final regulations and technical specifications for the federal exchange are still outstanding.

The skeptics are worried. Michael Cannon, the director of health policy studies at the libertarian Cato Institute, who has been advising state officials to fight the law through noncompliance, says he thinks HHS is behind schedule. "They have very little time to do this, and they really need the manpower," he said. "An indication of how difficult this is for the federal government is that they aren't telling anyone what kind of progress they've made."

Oklahoma has sued the federal government, arguing that the health care law's statutory language means that federal tax credits can't be offered in a federally run exchange. Maine has argued that the Supreme Court ruling about the law's Medicaid expansion throws other Medicaid provisions into question. Both suits are considered long shots, but they are evidence of the strong opposition that some states continue to express, even as the exchanges' effective date draws near.

Of course, there are politicians and there are bureaucrats. Officials in even the reddest of red-states have been quietly preparing for implementation. Michael Koetting, the deputy director for planning and reform implementation for the Healthcare and Family Services Department in Illinois, which will be sharing exchange-management responsibilities with the federal government, said he frequently talks to his counterparts in other states at meetings called by federal officials. "They want to make all of this work out somehow," he said. "The difference between that meeting, and, say, a meeting of the governors' association on exchanges that I went to is palpable."

Employers

The law creates these marketplaces for the minority of people who buy their own health coverage, but it also creates a raft of new rules for employers, still the dominant providers of insurance in the country. Any employer with the equivalent of more than 50 full-time workers is required to offer affordable coverage that meets minimum benefit standards for all of its employees who work more than 30 hours a week.

It will be a big change for nearly every company. For the largest corporations, which already offer comprehensive coverage to their salaried workers, these changes are significant but not too disruptive. But industries that have traditionally relied on hourly workforces or operate on tight margins are struggling to fit the rules into the law's employment model. If they fail to offer coverage, they will pay a per-employee penalty. If they offer coverage, but employees still buy on the exchanges, they will pay a penalty, too.

"No matter how many employees you have -- whether you're a smaller company or a larger company, I think you're going to have an issue," said Christine Pollack, the vice president of government affairs at the Retail Industry Leaders Association, a trade group for the big-box stores. "This is the single largest change to the employer-sponsored insurance system since its creation."

A recent survey conducted by the benefits consulting firm Mercer found that nearly a third of its clients expected the changes to raise their costs by more than 3 percent. Many employers told Mercer they were considering shifting more workers to part-time schedules or reducing the size of their workforces to avoid the requirements. "They're trying to figure out what are the alternate strategies," said Tracy Watts, a partner at Mercer.

How many businesses will end up shifting their workforces is yet to be seen. The restaurant group Darden, which owns the Olive Garden and Red Lobster chains, had said earlier this year that it would move more employees to part-time schedules to avoid the law's strictures. Last week, it changed course, saying it had determined that keeping full-time employees was a better business strategy. In Massachusetts, the retail and restaurant industries howled about similar requirements, but research from the Urban Institute found that several years after implementation of the state's health law, the state saw no disproportionate erosion in its share of full- or part-time jobs in those industries, despite the complaints.

However, it does seem clear that some businesses will struggle to absorb the additional cost of insurance -- which averages about $15,000 a year for a family plan, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Rebecca Lloyd, the vice president of Arnan Development Corp. and Otsego Ready Mix, in Oneonta, N.Y., said that her company has been offering health coverage to its low-wage workforce for years but is likely to drop it come 2014. Her business can't afford to offer family plans, making it eligible for penalties every time an employee's child enrolls in a public program. She's weighing the various options -- giving employees cash to spend in the exchange, trimming the size of her workforce, splitting up the company.

"How am I going to abide by the new rules and still provide for the employees?" Lloyd wondered. "Because the last thing I want to do is hurt our employees."

Lara Seligman contributed

This article appeared in the Saturday, December 15, 2012 edition of National Journal.

.jpg)