African American motorist Rodney King was beaten on the side of the road by four white Los Angeles police officers in March 1991. A year later, a verdict that cleared the officers of all but a single criminal charge triggered the Los Angeles riots, the biggest case of civil unrest in the city’s history.

King became a symbol of splintered race relations in the US. But there is an untold story, one in which his family exemplifies another painful phenomenon in American life.

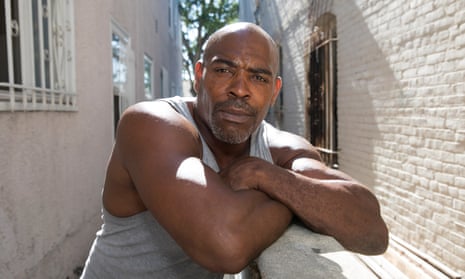

A few years before Rodney King’s beating, his younger brother, Juan, had taken to alcohol and drugs. His addictions worsened when the glare of the media turned on the family. “It was a family crisis. And I got depressed,” Juan said. He left his parents’ home for good, landing on the streets of Santa Monica, Hollywood, Pasadena and Skid Row.

“I’ve been homeless off and on for 25 years now,” he said.

Juan King fits a common profile of a homeless person in 2017: black, male and middle-aged. Minorities – namely African Americans and Latinos – have composed a disproportionate share of the nation’s homeless population for decades. Yet the implications are rarely acknowledged explicitly.

“People who work with the homeless see this obvious disproportionality,” said Karen Lincoln, an associate professor and expert in social work at the University of Southern California, “but it’s not something discussed in policy solutions.”

The recently announced results of this year’s homeless counts in cities such as San Francisco, Seattle and Portland confirm the trend: people of color are overrepresented. Some 40.4% of the national homeless population is black, according to the University of Maryland School of Public Health, although African Americans make up just 12.5% of the general population.

“Life right now is unpredictable for me,” said King. “Unfortunately, a lot of people of color are suffering worse.”

Minorities were only a sliver of the homelessness population in the early 20th century. Even in the 50s and 60s, the typical homeless person was white, male and in his 50s, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless.

A shift began in the 1970s and after, when homelessness started to emerge in its modern form, in the wake of major cuts to low income housing and mental healthcare resources that affected the poorest communities – often minorities – most severely. With the onset of the war on drugs, prison became a holding pen for drug users and those with psychiatric illnesses.

The crack cocaine epidemic of the 80s, meanwhile, brought black and Latino communities around the country “to rock bottom”, said Deon Joseph, an LAPD senior lead officer who patrols Skid Row in Los Angeles.

“Being African American and growing up in the 80s, I saw how this disproportionate problem of crack cocaine devastated communities of color,” Joseph said. “Some people could go get treatment in Malibu, but black and brown people ended up in prison, and we still see the effects today.”

Sky-high housing costs continue to disproportionately impact minority residents in major cities such as Los Angeles. They have lower rates of property ownership, face discrimination from landlords, and are still living with the legacy of racist practices like redlining, which segregated cities by denying loans to minorities in certain neighborhoods. A poverty trap is the result.

Juan King, now 50, grew up in a working class family in Altadena, in southern California. His father, Ronald, and mother, Odessa, cleaned houses for a living before starting a hospital janitorial business. Ronald died in 1984, and the four King brothers took over as breadwinners for the family, working in construction.

The partnership didn’t last long – “it’s really hard to work with family,” Juan said – and he drifted from his siblings. Rodney’s beating was a final blow of sorts to the family group.

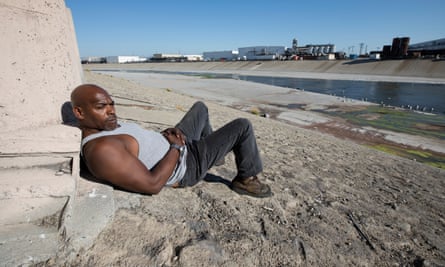

Juan says he always had the option to live in his mother’s home, but his drug addiction made him seek isolation. Instead he roamed sidewalks and shelters across the county. By 2010, Juan was living under a bridge on the banks of the Los Angeles River, with just a jacket and backpack as belongings. “The streets were my palace,” Juan said, with some irony.

It was clear to him that something wasn’t, and isn’t, right. Los Angeles county notched a record 58,000 homeless people in a count this year, but the impacts are far from evenly felt. Some 22,000 are African Americans, a 28% spike over last year. Even more dramatic was the 63% jump in homeless Hispanics and Latinos. The tally of white homeless people, however, decreased by 2%, and in absolute terms their numbers were also smaller than the other two groups.

The disparities are obvious on Skid Row, where more than 5,000 people sleep on the streets or in shelters each night. Its sidewalks feature a patchwork of tents, tarps, boxes and carts, with black and brown faces peeking out from pockets of shade that provide a modicum of respite from the blazing summer heat.

Humphrey Jones, a 58-year-old black man, has been homeless for the past three years, and on a recent afternoon sat on a quieter side street, carefully wiping down the shoes and other accessories he finds in the trash or on the street. Illness and poor financial choices forced him out in “the jungle”, he said, but he also linked his situation to racial and economic inequality. “Rich folks can’t keep getting richer unless some of us stay down,” he said.

He whipped off his dark baseball cap to rub his short, greying hair in frustration. Nearby, a friend who overheard reacted with surprise. “I guess I never realized, I never thought about how black everyone out here is,” said a slender black woman named Myra, 54. “It’s almost so obvious we forget.”

While Los Angeles recently allocated huge sums of money to resolving homelessness – nearly $5bn over 10 years – the plans do not address problems unique to impoverished people of color, said LA City councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson, who chairs the city’s homelessness committee. Funding for services based on race are not allowed under California law.

“Meanwhile, mass incarceration and other forces make it possible to discriminate against a person [based on race] for a long time,” Harris-Dawson said. “It’s also about a broken foster care system, which is disproportionately black in almost the same way as homelessness.”

The implication for advocates is that the resolution of homelessness involves tackling enduring racial inequality as well as a housing shortage. The King family knows the impact of these forces only too well. Rodney died in an accidental drowning while intoxicated in 2012, after years of drug use and arrests.

“He was a slow kid, but good-hearted. Rodney felt like he didn’t fit how the world wanted him to be,” Juan said. “He was always trying to clean up his life, but crack and alcohol just lower your ability to stay on track.”

During long nights under the bridge, Juan struggled with regret, and the feeling that he had wasted decades of his life. Several years ago, Juan finally committed to a program that would help him get sober, employed and off the street. It was a decision that saved his life in two ways: the center hosting the program, Union Station Homeless Services, ensured the treatment of his prostate cancer, and also arranged for his current apartment, a tiny, subsidized space in South LA, which he moved into in 2015 and rents for $350 a month.

It’s a rare stretch of stability for Juan, yet homelessness continues to stalk the King family.

King’s older brother, Ronald Jr, suffers from a variety of mental illnesses that seemed to Juan to stem from a car crash in 1987. “The accident left him paranoid, not wanting to be inside a house,” he said.

“He’s still out on the streets in LA as far as I know.”

Do you have an experience of homelessness to share with the Guardian? Get in touch