In April of 2015, Janet Delaney was driving around SoMa, looking for subjects to photograph for her ongoing “SoMa Now” series. When she saw a man reclined on the corner of Eighth and Folsom streets, a shiny walker by his side, she immediately pulled over.

“It was the same kind of walker I had been using when I got my hip replaced about a year or two before,” Delaney recalled. “And I thought, 'That’s a high-quality walker for someone just lying on the street.' For some reason, I felt compelled to talk to him. So I sat down on the curb next to him and we had a great conversation.”

Delaney learned that the man had been released from the hospital only three days earlier after breaking his femur. Having gone through a similar recovery herself, she marveled at the idea of him sleeping on the street. Nevertheless, he was cheerful and happy to talk with her, and even let her take his photograph.

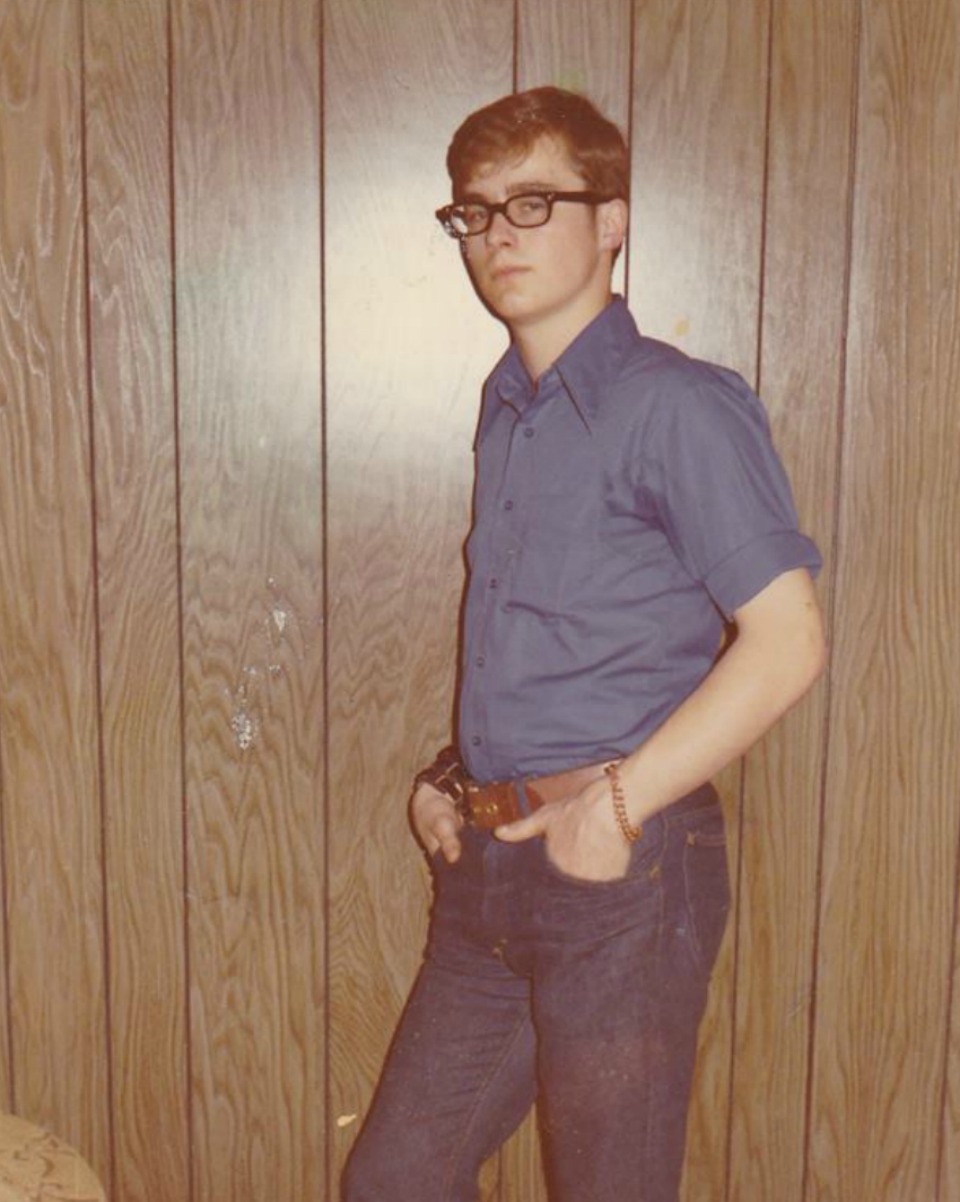

Over the next couple of months, Delaney would stop by whenever she was in the area. She found him in the same spot every time, sometimes holding forth with friends, sometimes alone, but always eager to talk. Although he was missing most of his teeth and was difficult to understand, he was very forthcoming. He told Delaney he used to live in Texas. He mentioned having an ex-wife and children, but said he couldn’t go back to them because he was bisexual and they just wouldn’t understand. He also admitted that he had broken his femur because he had been drinking, something for which he felt ashamed.

The last time Delaney saw him, in December, he had a small dog with him. He was taking care of it for a friend of his who had recently gone to jail. Besides a blanket, a jacket, and a couple of cigarettes, the dog was one of his only possessions. Though he would occasionally accept a few dollars or a bite to eat, Delaney never remembered him asking for anything. He wouldn’t even hold out his hand.

The following March, the man admitted himself to the general hospital, complaining of stomach pains. Cancer was eating its way through his body. He died on Saturday, March 26th, 2016. The next day was Easter Sunday.

Photo: Google STREET VIEW

His name was Steve Pollard, and he was one of the several dozen homeless men and women in San Francisco who will die this year. According to data compiled by the Medical Examiner’s Office and the Department of Public Health, 41 homeless people died between the Decembers of 2014 and 2015. In the decade since the city has been keeping track, this was an average year: a low of 15 people died in 2009, while 2006 brought a high of 83.

It should come as no surprise that homelessness is deadly. In fact, a recent study by UC Berkeley that focused on homeless youths in San Francisco found that they are 10 times more likely to die than their peers. The most likely causes are suicide or substance abuse, although the general homeless population suffers from a whole host of additional ailments, including untreated medical and mental health conditions, high rates of assault and violent crime, and the constant stress and pressure of extreme poverty.

The result of this has been the creation of countless programs designed to help serve the homelessness, alleviate their challenges, and reduce their numbers. In San Francisco alone, the San Francisco Chronicle found, the city spends over $241 million a year on homeless services, spread across 400 contracts and 76 private organizations — a number that doesn’t even include the sums spent on the emergency responders that regularly help homeless people in need. There are also the hundreds of SROs spread throughout the city, which give many homeless temporary relief, as well as the numerous nonprofits, clinics, religious organizations, and individuals whose mission it is to help the homeless.

Yet they remain — 6,600 or so according to last year’s Point-in-Time Count and Survey — filling shelters and sitting on streets and (most recently) pitching tents, all the while fanning the flames of debate amongst San Francisco residents about what to do.

Some, like Sup. David Campos, want even more spending, as well as the construction of more shelters like the Navigation Center on Mission and 16th. Others want to see a consolidation of the city’s various homeless programs in order to streamline their services. Many have simply responded to the mayor’s plan to sweep away the encampments that have been growing along Division and other streets for the past few months.

Often lost in all this discussion, however, is the human element of homelessness, a grim irony that can be most poignant when a homeless person dies, and the procedures of government protocol suddenly converge with the families and loved ones whom they leave behind.

“I wish I would have known,” said Tricia Mittman. “If I’d had known, I would have flown my butt out there and brought him back.”

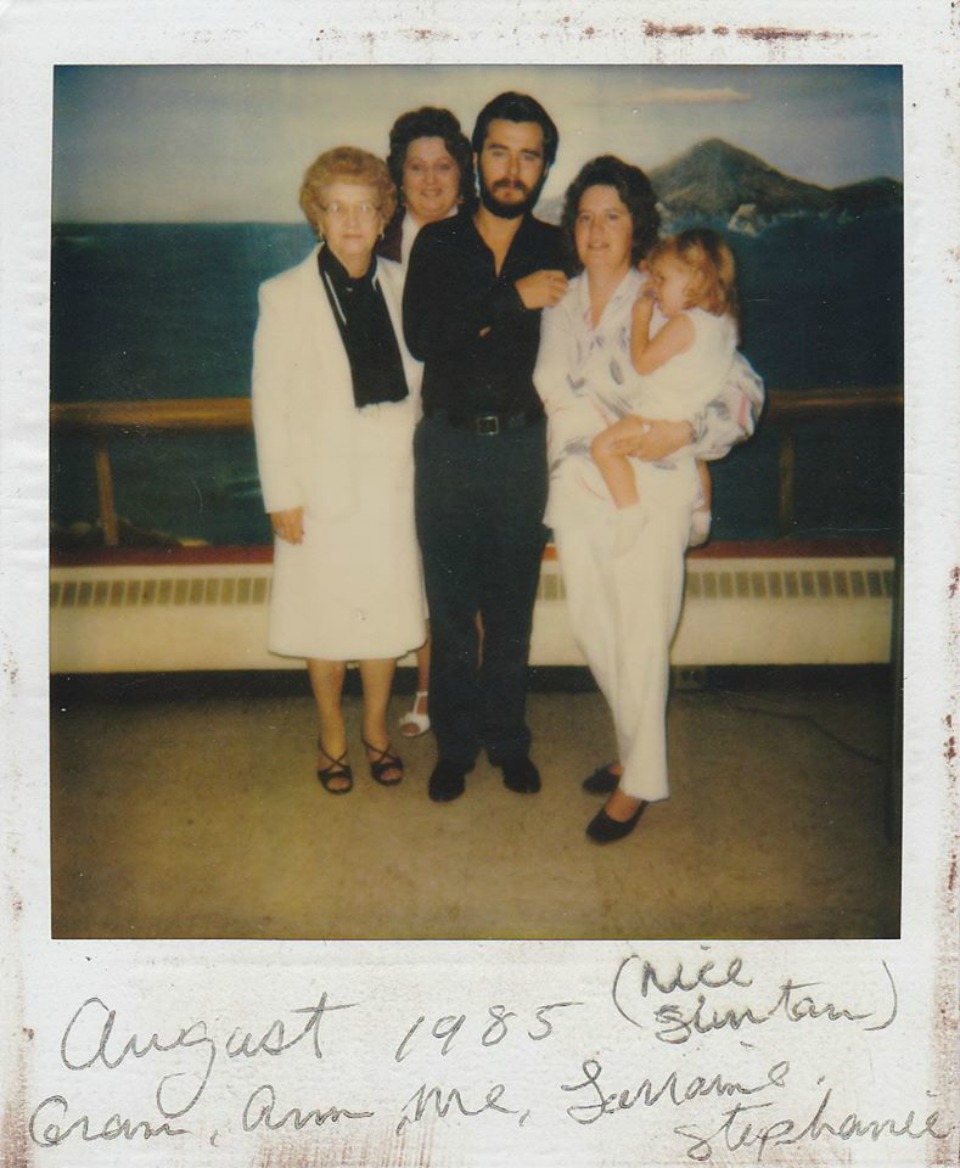

Mittman is Steve Pollard’s niece. She and her family, all of whom live in Ohio, received a call from the UCSF Medical Center the day before he died, informing them that he had slipped into a coma and was on life support. They needed permission to take him off. Mittman, who was one of the family members closest to Steve, hadn’t heard from him for over five years. Some in the family, like his daughter, hadn’t seen or spoken with him in decades. Before that phone call, in fact, no one was even sure where he was. Now they learned he had a brain hemorrhage, multiple tumors, and little chance of recovery. They decided they had little choice but to authorize taking her uncle off life support.

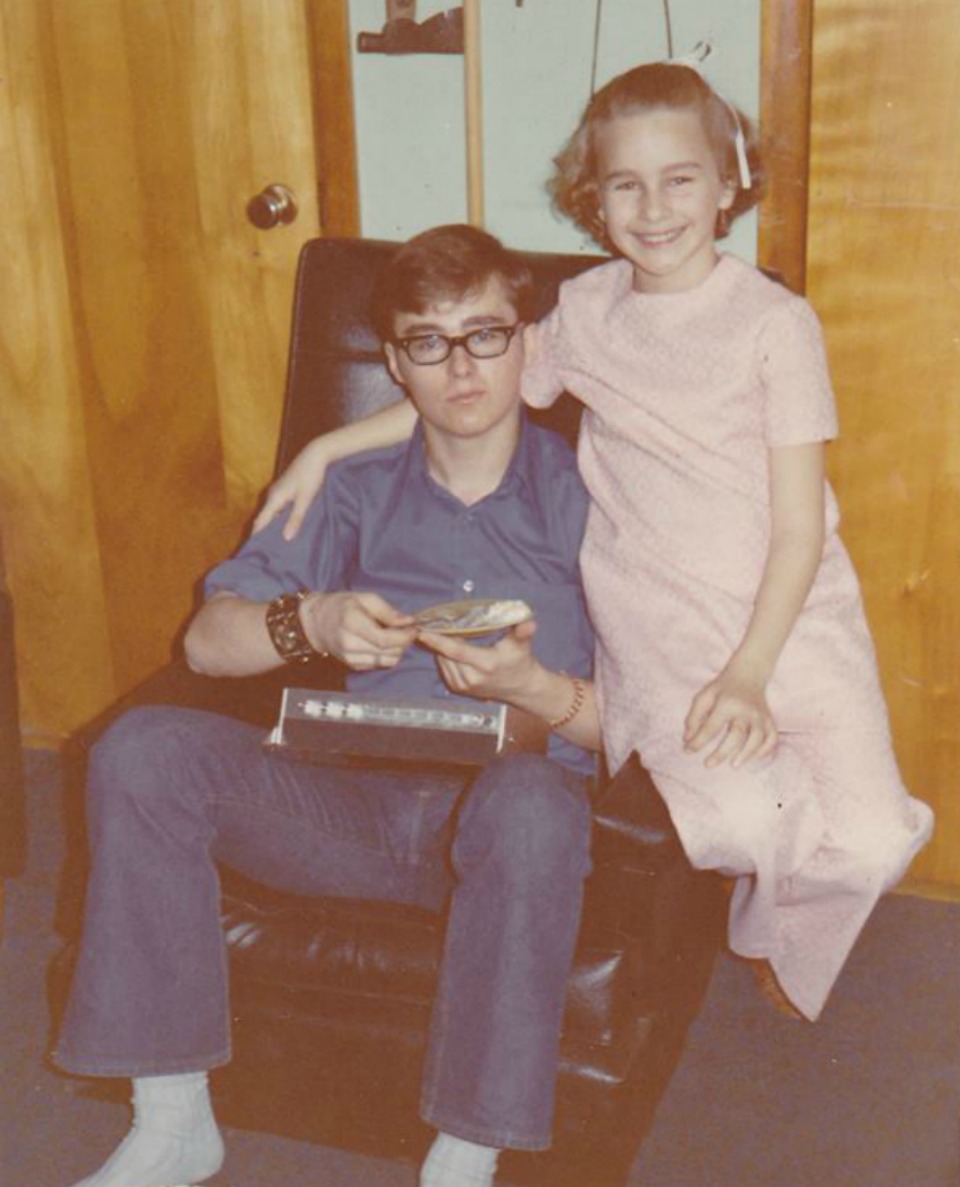

Afterwards, Mittman couldn’t stop thinking about Steve. About six or seven years ago, she explained, she had decided to track him down. As long as she had known him, he had been a drifter, loathe to spend too much time in one place before moving on, but she had fond memories of her uncle from when she was a child (Mittman is now 36), and wanted to reconnect.

She began searching for him online, typing his name into Google and signing up for sites like Ancestry.com. When that didn’t work, she took the suggestion of her father (Steve’s brother) and began contacting prisons. Eventually, she located a Steve Pollard who was serving a stint at San Quentin.

“I took the leap and decided to write him,” Mittman recalled. “I didn’t even know if it was Steve. I had this inmate number, and I addressed [my letter] to San Quentin State Prison, care of Steve Pollard, and waited to see if I ever heard anything. Lo and behold, I was soon getting letters almost every single day from Steve. It was him.”

This went on for about six months. Mittman filled him in on family news, such as the death of Steve’s father, while Steve shared small details of his life, like the stroke that had left him walking with a cane. Once or twice, Mittman tried delicately to find out why Steve was in prison, but he was reluctant to tell her too much, a silence she attributed to his shame. Instead, he would decorate his envelopes with intricate drawings, recalling a time when he had aspired to make a living off his art.

In the last letter she received from him, Steve told Mittman that he would soon be released. When several months passed with no word, though, she tried contacting San Quentin to see if he had been sent to a group home or a rehab facility, but they wouldn’t give her any information. She kept searching for him, here and there, but it was in vain. He had vanished once again—at least until the day they received that call.

What happens when a homeless person, long estranged from his family, dies? The answer will often vary.

In San Francisco, when an individual dies with no next-of-kin listed, it is up to the Office of the Medical Examiner to locate his or her family. After identifying the body, which may involve fingerprinting if no ID is found, their investigative division begins looking for clues.

“We use a variety of resources,” said Christopher Wirowek, the deputy director of the Medical Examiner’s Office. These include cross-checking the deceased's identity on different electronic databases and with veteran’s affairs, as well as looking through any items found within personal property, such as any old holiday cards, mail, and contact lists on cell phones. “Facebook has even proven useful,” Wirowek mentioned, “although it’s not something we do routinely.”

If the family is found, Wirowek emphasized that his office will do whatever it can to fulfill the family's wishes so that the entire process is as painless as possible. They will transport the body to the family if requested, or cremate it and send the family the remains. If the family consents to it, and the body is in a good enough condition (i.e., it is discovered shortly after death, before the process of decomposition has begun), the Medical Examiner's Office will even donate it for medical and research purposes. However, due to the large number of solitary and/or traumatic deaths, Wirowek conceded that this is rare.

In the event that next-of-kin cannot be found, the Medical Examiner’s Office becomes the body’s “family” itself. Due to space limitations, the body will be cremated, with the ashes then stored for up to a year. If no one has come forward after that, their ashes will be taken out to the Pacific Ocean with the remains of other unclaimed persons, and scattered at sea.

Photo: Janet Delaney

In some sense, Steve Pollard’s family was lucky. He not only died in a hospital, where he could be safely monitored in the moments before his death, but he had had the foresight to list his daughter — whom he had never had a relationship with — as his next-of-kin. Mittman admitted that news of Steve's grave condition came as a surprise to the family, but they considered themselves fortunate to have received that news before his death.

However, they were less fortunate in another sense, mainly that they suddenly had to come to terms with the life and death of a family member whom they barely knew. “Why?” Mittman said over the phone. “Why didn’t he reach out? Is this really how we have to remember him? On the street as a homeless man?”

So, shortly after the phone call, unable to sleep, Mittman began looking for him again. The little that she knew of his life was tragic — alcoholic parents, a series of neglectful foster homes, a childhood marred by mental and physical abuse — but she also remembered him as her uncle, hanging out with her dad, working on automobiles all day in the garage. She wanted to fill in some of the blanks and learn something about who he was.

Like before, she put his name into Google and began searching for him, except this time she found something new. “I’m scrolling through the images,” Mittman recalled, “and I come past this picture that is so tiny and unbelievable, you could barely even make it out what it was. I click on it and my heart sunk. I went, ‘Oh my God, that’s Uncle Steve!’”

She had found the photograph Janet Delaney took in April of 2015. He looked like he had aged 50 years, but it was definitely him. Mittman decided to write to Delaney.

“The ground moves a little,” Delaney said, describing what it was like to learn from Mittman that Steve had died. “I felt like I had to do some sort of ritual to acknowledge this.”

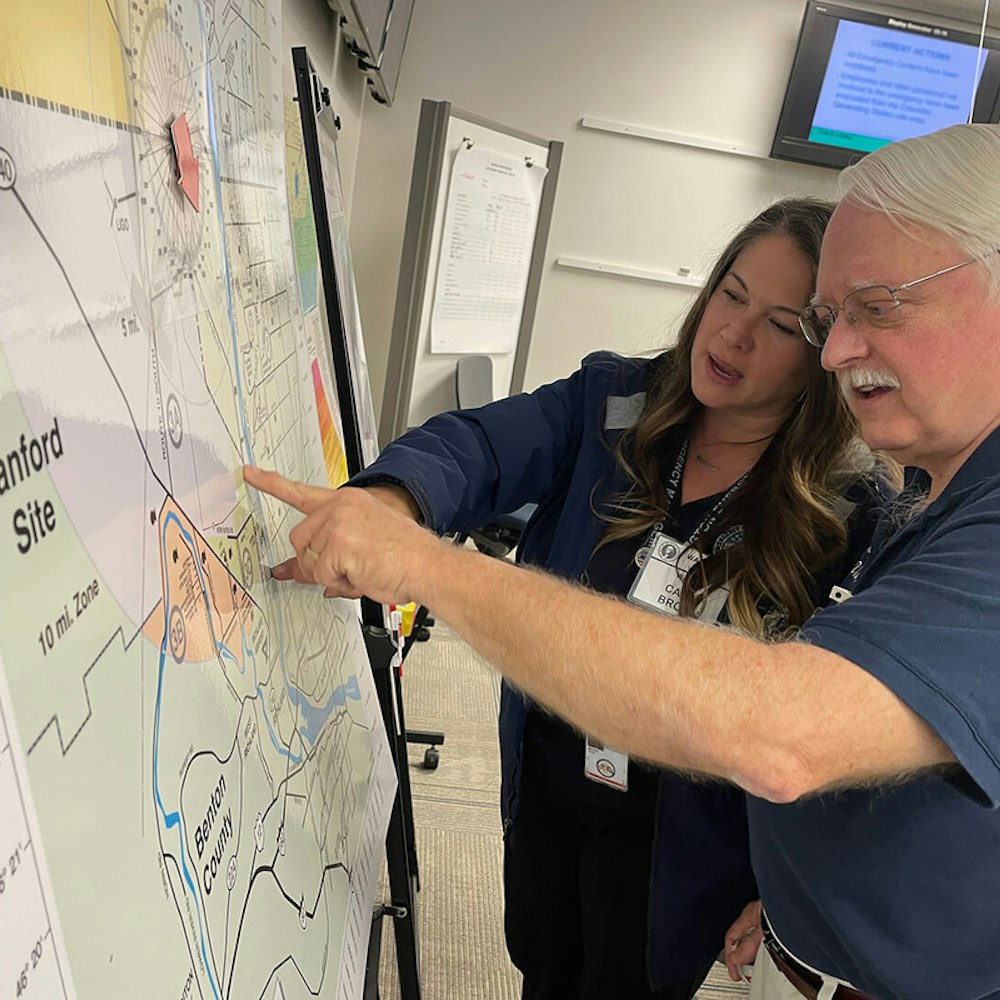

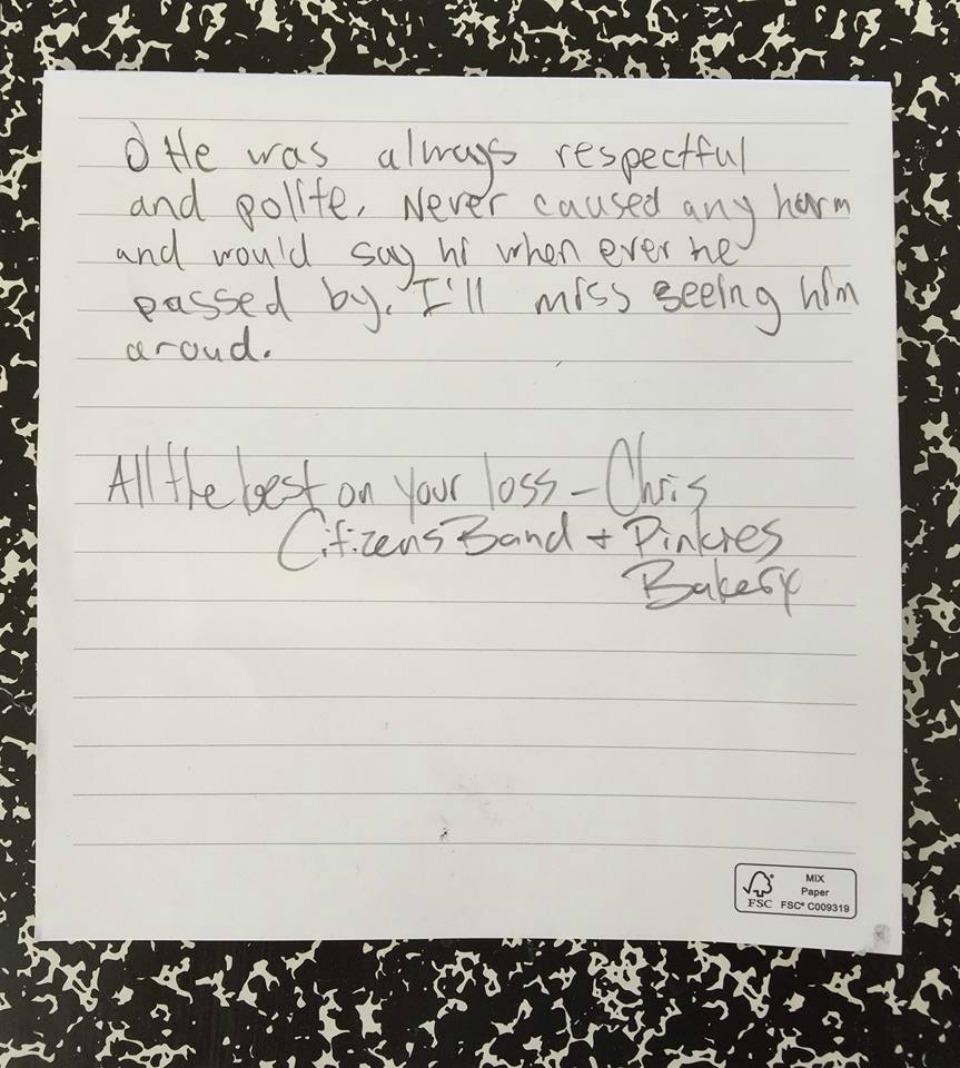

She wrote back to Mittman, telling her what little she knew, then returned to the corner he often sat at, on Eighth and Folsom, to post a sign with a picture of Steve, along with his story. With it, she included a note inviting anyone who wanted to send a message to the family to leave a note or email her. She did the same at a couple of cafes she knew he frequented.

Soon after, the letters began pouring in.

“He was always respectful and polite. Never caused any harm and would always say hi whenever he passed by,” said one. “I’ll miss seeing him around.”

“Just wanted to say that I was quite sad to hear the news about Steve,” said another. “He was very kind and courteous, always saying hello or good night. I never would have guessed he was so sick.”

They shared memories of Steve walking with them down the street, or of the gratefulness with which he accepted a few dollars so he could give himself a shave. They described how happy he was with his broom and vest when he got a job sweeping the street. They spoke of his smile, of how he would always be there as they came and went.

Taken individually, they are small, almost incidental — just glimpses into his life. For Mittman and her family, though, all these responses helped answer, if only a tiny bit, the question of who Steve was.

Despite the vitriol and intense emotions that can often define the homeless debate, there is actually a great deal of consensus about just what should be done. The solution is so obvious it is nearly banal: to eliminate homelessness, simply give these people homes.

Of course, in reality, it is not so simple. This is especially true in a city like San Francisco, where the argument over affordable housing and what gets built in our backyard may rival even that of homelessness (although the two are inextricably linked). For example, although the Navigation Center has been one of the most potent success stories in the fight against homelessness in recent years, David Campos has been unable to find any neighborhood willing to hold another one. The prospect of permanent housing within the Bay Area for those currently homeless seems even more bleak.

However, the story of Steve Pollard should contain an interesting lesson. The homeless masses may be ignored or forgotten in the minds of many of the city’s residents, but there are likely a sizable number who have families, friends, or loved ones who are wondering about them, who would very much like to know where they are. And if they knew, maybe they would be willing to give them a home.

As it happens, this is not a new idea. Since 2005, Homeward Bound has been helping homeless individuals in San Francisco leave their current situation and relocate to a place where they will have a home. From when they launched their services through December of last year, they have helped 9,560 people escape homelessness in San Francisco, at an average cost of $186 per person.

Although the program has previously received criticism for doing little more than exporting the homeless problem elsewhere, they insist this is not what they are about. “We do not send anyone anywhere unless we can confirm that there’s someone who will take them in on the other end,” emphasized Scott Walton, Adult Services Manager of the Housing and Homeless Division, which oversees Homeward Bound. “We are not relocating people to be homeless somewhere else.”

The success of the program has recently led to its expansion from two employees to nine. This includes a staff of outreach workers whose job it is to meet with the homeless in order to explain the program and hopefully convince them to join. However, it remains entirely up to the individual whether or not they want to take advantage of this service. Even if a friend or family member who is trying to locate someone reaches out to Homeward Bound, all they can do is pass on the information. Ultimately, it is not their decision to make.

This, finally, gets at one of the most enduring tragedies of Steve Pollard and the dozens like him who will die, lonely but perhaps not yet forgotten, in hospital beds and shelters and out on the street: there is no one solution. Put another way, the burden of change does not fall on a single program or department or well-imagined law, but on society as a whole. A problem like homelessness does not plant its roots in the minds of damaged individuals, but in the shortcomings of our communities.

After all, what would have prevented Steve Pollard’s homelessness and his subsequent death? Perhaps if he had received a more supportive upbringing, or had access to better rehabilitation services while in jail. Or maybe if he had been given more options afterwards than simply wandering the streets. Or maybe some secret combination of these, or maybe none of them at all.

“Why?” Mittman repeated, her voice plaintive, as she pondered this question aloud. Mittman and her family are currently waiting for Steve’s ashes to be delivered to their home.

“We don’t care if he was bisexual. We don’t have anything against the homeless. I just don’t know. Honestly, I wish I had an answer. I wish he was alive to tell me, but he’s not. Because I would have helped him in a heartbeat.”