Our Inevitable Future: A Conversation With Kevin Kelly About VR, Digital Socialism, And His New Book

If you’re a virtual reality enthusiast, you probably read Kevin Kelly’s April Wired cover story on Magic Leap, “The World’s Most Secretive Startup.” Kelly is one of the few people who’ve seen the much-hyped mixed reality technology being produced by the Fort Lauderdale company and was suitably impressed by it. “While Magic Leap has yet to achieve the immersion of The Void,” he wrote (referring to the Utah-based immersive experience company), “it is still, by far, the most impressive on the visual front — the best at creating the illusion that virtual objects truly exist.”

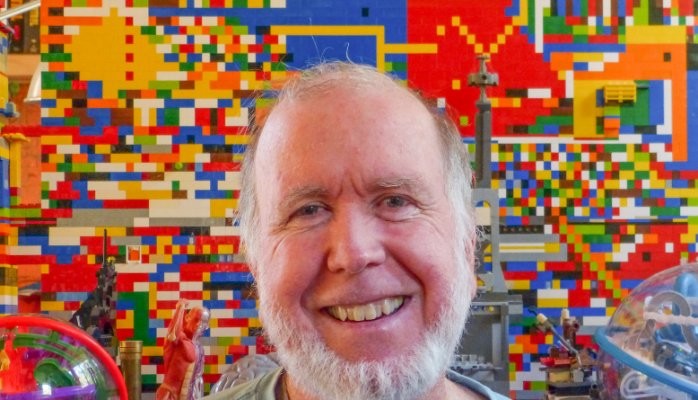

As the co-founder of Wired, publisher of the Cool Tools website, and former publisher and editor of The Whole Earth Review, Kelly has always been prescient about these things. In his new book, The Inevitable: Understanding 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future, he compellingly outlines a set of behaviors and trends that will change the way we live. We recently spoke with Kelly about the themes of the book, and of course, the latest developments in VR.

[The interview below has been edited for clarity, and condensed, though admittedly, not very much.]

There Is Only R: The first question I have to ask: what do you think of the Pokemon Go phenomenon? Given what you’ve written about the VR and AR, what’s your take on it?

Kevin Kelly: I think it’s just wonderfully thrilling to see — I think perhaps the only unexpected thing about it is its apparent suddenness. I was just walking around last night in our neighborhood, and there were all these little Poke stores and everything. It was kind of piggybacking on [prior AR app] Ingress sort of like, I don’t know, like a sleeper cell or something. People including me have been talking about GoogleEarth and GoogleMaps as kind of a bed for VR for a long time, and I think what it’s shown is how you could do mixed reality and what that might be like.

And I think no matter what happens to Pokemon Go, I think there’ll now be a lot more tries, a lot more attempts to do something on top of it. I’m trying to think what the equivalent would be. It’s sort of like the early days of video arcade games, where they were good enough to improve. You had Pong and you had Pac-Man, and people saw that people would pay money for those, and then we had this explosion where everybody else was trying to do something better.

I wonder if just the simplicity of Pokemon Go made it popular. You can pretty much figure out how to play Pokemon Go if you know nothing about Pokemon or AR even.

I’m assuming they just tapped into the interface in a way that Ingress didn’t. And there obviously were network effects. You saw people doing it and that propelled you to try it, and the more people that tried it, the more obvious it became.

So that wonderful thing about the public aspect of it is, I don’t know if it’s going to be repeated again. Because later when people are doing it, you won’t know what they’re doing. There will be all these games and right now when you see somebody out on the street looking at [a device], there’s only one thing they could be doing.

When you write books like this where you’re making some hard predictions about the future, I would imagine that somewhere between the book going to press and it actually coming out, some of the things you write about actually happened. Is there anything that happened with this book?

Well, I did a lot more on VR which is your kind of domain, that I wish New York publishing was fast enough to put into the book. The text for The Inevitable was actually completed a year ago. I finished writing the stuff for VR in December. So I had a lot more firsthand experience and additional thoughts on what VR and AR mean to the world that’s not in the book. I wish I could’ve included it.

There are lots of different ways to deal with complex ideas. I think, and I write about this in my book under the screen chapter, where there’s this marriage of text and moving images — video that you read, books that you watch. I think there’s something there that I want to explore, this convergence marriage of text and moving images together. I have another project that I’m thinking of for VR.

It’s really hard to kind of invent both the medium and content at the same time, and I’m not actually that interested in inventing the medium. I would prefer to take some of that stuff that exists and make content for it because every attempt I’ve seen in the past for someone to try and do both, it just doesn’t work. They’re really two different mindsets, I think. And my inclination right now is to let others invent the medium and I’ll try and make some content.

Yeah, what we’re seeing is a lot of people we think would be in the market to develop content are kind of holding off because they want to see wider adoption in VR. Is that what you’re seeing?

Well, I am seeing that, but I’m personally not worried about it. I just think that the tools are not there for me yet. I’m not so concerned about audience size — I don’t need a big audience. If you have direct contact with your fans — a thousand true fans — you don’t need these large audiences that big, big media companies need.

I think it’s more just the absence of really good tools, not just the production tools, but even the appropriate form factors. Right now we have very crude tools.

When I see VR experiences that are a little bit less impressive, I always think it’s because the creators are trying to take 2D formats and translate them directly.

Yeah, absolutely, and in the early days of the internet, we used to call [that phenomenon] shovel-ware, because you would take content from your magazine and you would just shovel it onto the web. And it was very evident to everybody that that wasn’t going to work. So we actually had a whole separate editorial team working on content for the digital side of Wired, completely independent of the magazine side because we just knew it was going to require a different logic, a different workflow, different frequency.

With VR, there’s definitely a tendency to make some of these narratives like movies and movie people are making them. And it’ll take some years before we figure out what the new norms are — what works, what doesn’t work.

And this is something you can’t figure out by thinking about it. The smartest genius in the world could be applied to figuring this out in theory, but it is something that we only figure out by using VR. And no amount of preconception, pre-visualizing it is going to be able to solve this. I think we’re going to need like 10,000 hours of experience in order to make any changes, to move in the right direction.

So who do you think is going to be on the forefront of that? Who do you think is gonna do the really innovative stuff and most experimental content creators are gonna be?

My bias is that the studios will spend a lot of money trying this, but it’s the Buzzfeeds of the world that will come along and make something that will actually work. I think we’re far from even seeing, even formation of these companies that will succeed. I think they haven’t been formed yet, or maybe they’re forming in the basement right now as we speak, but it’s still years away.

My bias is that the studios will spend a lot of money trying this, but it’s the Buzzfeeds of the world that will come along and make something that will actually work.

I think some of the gaming companies, people you know, might have the first round of successes, but I think it’s gonna take five years for the other forms. It’s gonna be a little slow in the beginning. I don’t see any kind of VR unicorns happening within five years.

When you submitted the book — had you seen Magic Leap yet?

No, I had not. I had not seen Magic Leap when the book was done. I had not seen Meta, and I’d not seen Hololens and I had not seen The Void, so I had not seen the major players when I wrote the chapter on VR in my book. I’d only seen The Oculus prototypes — the DK2.

And I’d seen the early stuff of Jaron [Lanier]’s. So that’s something I would like to have updated.

Yeah, you talk a little about being in Jaron’s lab in ’89 or ’90. [Jaron Lanier was an early VR pioneer who coined the term “virtual reality.”] What do you think he really got right at the time and what were people working in VR at that stage wrong about?

I don’t think they were wrong about very much. The quality of the experience at that time was actually not that far off from say, the Oculus. The resolution was not as great, but depth of feel was not that different. You had hands [in the experience] — you had gloves which were actually higher resolution than Oculus. And it was social. You had more than one person, and they had an articulated body.

Other experiments that were going on were pretty sophisticated. The thing that they sort of didn’t get right or the thing they didn’t have was that they weren’t cheap. They were just way too experimental and also they were too expensive in two ways — one was the money, and two was the maintenance.

So keeping those systems going required professional hacking help. You needed a person to maintain them, so it wasn’t just the purchase price, it was the fact that these things were temperamental and the tracking was always going off. It was not plug and play level. The thing that happened in those intervening years was not so much that the quality drastically improved, but simply that the price changed by three orders of magnitude.

So now we’re at this level where they you have a great flywheel effect.

In your chapter on cognifying, you say — and forgive me if I’m oversimplifying — that you can layer AI into pretty much anything and it makes a huge difference. How do you see AI changing VR as we know it right now?

I see AR and VR as like peanut butter and jelly. I think that to curate the kinds of worlds that we expect and want in virtual reality, you need ubiquitous cheap AI. A lot of what the VR world would be doing would be anticipating or tracking, capturing our movements in order to affect some change.

And from the small level of recreating physics to being able to recognize a gesture or a movement will just require constant, ubiquitous, cheap AI machinery in some capacity. And if we start to add these additional little tricks like redirected walking and other kinds of magical misdirection that can enhance and make it practical in the kind of tight spaces that we actually operate in, that’s another order of AI that’s necessary to process all the stuff in the background.

And then there’s the whole gaming aspect where you’re populating it, not just with people, but these other agents, or agencies — things from the weather to serendipitous encounters. And they all require more AI horsepower, and so I just think that the two are going to grow up together.

And I don’t imagine that the VR companies will manufacture the AI. I think they’re going to be purchasing it from AI companies, just as they’ll be purchasing electricity to run their service. But they will become a huge customer of AI.

I don’t imagine that the VR companies will manufacture the AI… But they will become a huge customer of AI.

To do AI, you don’t need a lot of people. But I think to do VR and the data, I think these are gonna be kind of immense companies that will be capturing huge swaths of human behavior and making entire economies, virtual economies, and virtual lives, and virtual relationships. It’ll require huge, huge amounts of data, and huge amounts of bandwidth. And that mobile bandwidth, all that infrastructure, is immense. You need seven cameras to do a full roomscale VR, and that light field data has to be processed. It’s a great opportunity for a whole industry that’s going to serve the needs of VR worlds.

Earlier I read an interview with Ray Kurzweil in Playboy from a few months ago. He has kind of a different scenario for AI and VR that’s a little bit more sci-fi. He says that by 2030 we’ll have VR tech embedded in our nervous system, like chipped into the neocortex or something like that. What do you think of that scenario? Does that seem plausible to you?

Not in 2030. There are none of the precursors necessary for that to happen in 2030. I think as soon as you start messing with the human body, you’re talking about a different time scale. Digital stuff can progress at this exponential rate, but if you’re messing with the human body, you have to do more.

We’re susceptible to what I call “thinkism”, which is this idea that thinking about things can solve problems — that if you had an AI that was smart enough, you could solve cancer because you could think about it.

We’re susceptible to what I call “thinkism”, which is this idea that thinking about things can solve problems — that if you had an AI that was smart enough, you could solve cancer because you could think about it.

But we don’t know enough. We don’t have enough data, we don’t have enough experiments. You have to actually do a whole lot more experiments on cells, and human biology, and humans before you could solve it. You can’t just solve it by thinking about it.

And so the it’s same thing with this implant idea. It doesn’t take into any account the fact that you have to experiment on animals long before you get to humans, and that just takes biological time. [Kurzweil] will say, well, you can simulate them. But that doesn’t work. We just don’t know enough.

I think someday we’ll figure this out, but not anywhere near the ’30 year because we don’t have enough experimental data to do that.

So he’s not a futurist, but I noticed that Ernest Cline is quoted on the cover of your book. What do you think of the Ready Player One scenario for VR where we spend as much time in VR and social VR as the bulk of our human experience outside of it?

I think the idea of having this pervasive, continuous, broad, vast universe: that seems entirely reasonable to me. I think the question maybe comes down to how much time we’ll spend in it. And the curious thing about the online world was that people were asking this exact same question in the ’80s, when the first people were going online and going to bulletin boards. It was all just this text, and they were imagining that in the future, 30 years from now, everybody would be in their basement, and they would never leave. We would all be online in virtual communities.

What happened, of course, was very, very different. One of the things that we noticed when we did The Well in the mid-‘80s was that the first thing people demanded once they started meeting online, was that they wanted to meet face-to-face. And you can draw a pretty good parallel line between the amount of hours you spend online and the amount of travel there is. Travel has not decreased; travel has increased.

I don’t know if it’s causation, but there’s certainly a correlation that meeting and being able to do things online actually emphasizes the power and the benefits that we get face-to-face. And so I think as good as VR gets, it’s a different experience meeting face to face. And that’ll be true for a very, very long time.

More likely that what we will get is increasing options and choices with very few of the old ones going away. While we will have plenty of virtual travel and people will have incredible experiences online, it will make the real trip in the plane to somewhere else ever more valuable and precious.

There’s another place in the book, where you refer to VR as a potential experience factory, and you talk a lot about a scenario where we all essentially own nothing. Or we don’t own a lot of things that we think of as important to own right now.

Do you think that’s in any way at odds with say, traditional American notions of success? I immediately thought about the housing crisis and the emphasis on home ownership that helped to precipitate it. Do you think maybe our thinking around that is changing? Or is this something unique?

In my book I thought about the shift from ownership to access — that if you have instant ubiquitous access anywhere anytime, that that can often service you better than ownership. Even if it’s not exactly instant, even if say within an hour you could have something physical that you wanted.

If you can have this thing delivered to you and then have it taken away when you’re done, that access can have more benefits to us than ownership. And since ownership is sort of the basis of our capitalistic society and notions of wealth, then moving away from that ownership would be a huge disruption.

And there’s several things to say about that: One is that I was trying to imagine a world in which somebody didn’t own anything and I don’t think that’s really reasonable or likely, but it was kind of a thought experiment just to show you an extreme what it would be like. But in fact, in order to have this world where people are accessing, somebody has to own something, right?

You may be summoning a car or a ride from somebody, but that person, somebody has to own and something to charge, but I think what happens is that we become a little bit more curated — that we own some things that we care about or that constitute our business. And the other things, things that we don’t care about, basically, we would subscribe to.

So we wouldn’t have universal ownership; we would have selective ownership. In some cases that selective ownership may be a way we display our status. In other cases it’s because it’s something we’re passionate about, and other cases it’s because we’re doing it to make money.

But home ownership all you’d have to do is take away the tax deducted mortgage subsidy and that would change really quick.

And that could happen too, by the way, but I do think there would be a change in our identity, in our conception of ourselves. Maybe there’s some home ownership, but it’s nothing that is as important. As far as I can tell, banks own the houses anyway today. It’s not really the homeowners, so I think we’ll continue to kind of blur those lines.

Speaking of those politics, when you talk about digital socialism, how do you envision that affecting, for instance, social justice movements like Black Lives Matter?

I think it’s a very complicated answer because on one level it doesn’t have a direct effect. On other levels, it’s obvious that there are things like tracking, ubiquitous cameras everywhere, and that makes a difference. The technological environment in which everything is filmed all the time will have a huge impact. In the end the cops are filming, and they should be filming, and the citizens should be filming — and citizens should have access to everything the cops film. The net effect will be good overall if everything is captured. Over time the greater good would be served by having that evidence.

But at the same time, it doesn’t address the fundamental problems, so I think it’s complicated.

It’s a little bit of a subversion of the way we think about surveillance, where it’s always state down. And we think of it as a way for the state will hold the citizenry accountable, but it seems like what we’re seeing now is a reversal of that. Given that you turned in the book about a year ago, is there anything you thinking about while you were writing that seems particularly poignant right now, given the very odd political environment we’re in?

My take on a lot of the anger, frustration that’s being represented by both the British exit and Trump, is that they’re derived from the fact that we have technological changes, changes in people’s livelihoods. Technology is taking away some of their jobs, and makes it hard for them to find work and have meaning in life. And they’re frustrated, and it has nothing to do with Mexico, or China or the immigrants in Syria. It has everything to do with the fact that automation is coming, will continue to come and that some of those changes will continue to happen.

The most common occupation in America is truck driving. There are three million truck drivers and their lives and livelihoods are going to be disrupted hugely by AI automated cars, so we’re not at the end of this. This is still going to continue.

So I don’t think we’ve heard the end of it.

actor at Sony Pictures Entertainment

2yI am in Santa Rosa, CA

actor at Sony Pictures Entertainment

2ygood day, russ! we are doing a grand jury and I am being elected to be the foreman, although I understand how to operate it, I wanted to make sure I am doing everything correctly and am requesting your help... can you please contact me at geminiii@tutanota.com... my name is Tamara, thank you !!

MAIL CLERK/SHIPPER at Stewart Title

7yHi John, I miss that smile

Manager, Processing at Scotiabank

7yDefinitely a thorough, provocative read!

Struggling Author

7yWow are we still doing this. Guess more likes for me...