The artist's first flowering is a big deal in any memoir. Li Kunwu's comes in the mid-1960s when he and his friends are on a Mao-inspired crusade. "Complicated haircuts are a legacy of the decadent classes," rules ringleader Hongbao, but the sly local hairdresser claims his illiterate clientele won't be able to read the list of restrictions they've written. So 11-year-old Li spends the night sketching barnet after barnet, marking stray curls, fancy bows and anything else that might get in the way of serious labour with a bold "X". The signs go up, the hairdresser glowers, and Li can celebrate: "It was my first artistic success, and it wasn't just any success. It was a revolutionary success."

The incident – which manages to be both a youthful jape and a depressing suppression of freedom – is told straight and unapologetically by an artist who was born in China's poor southwest in 1955, who went hungry in the Great Leap Forward, tramped borders for the People's Liberation Army, drew cartoons for his province's paper and ended up hobnobbing with mineral-water magnates in the southwestern city of Kunming, and French artists at Angoulême's famous comics festival.

Li's epic memoir, serialised in France between 2009 and 2011, was co-written with French writer and diplomat Ôtié. If you don't know your Chinese history, parts of it will mystify, and stretches of this 700-page odyssey drag a little. But this very human march through the making of modern China deserves a wide audience.

Li, the son of a party official and a peasant woman from the hills, grows up in an age of reform. Keen to "beat the Brits and catch up with the Americans", the people give up their iron for smelting, chop down forests to fuel furnaces and tear down pagodas for manure. Folklore is suppressed, farms are collectivised and famine batters town and country. Then the Cultural Revolution comes, bringing purges and paranoia, as Li and his classmates follow the Red Guard with doe-eyed enthusiasm, and gleefully denounce their neighbours.

Historians dispute the impact of China's postwar reforms – although few deny that millions died in the brutally mismanaged Great Leap Forward. A Chinese Life's ground-level perspective focuses on anecdote rather than statistics: the uncle gored to death while trying to steal food from a buffalo; Li swatting flies as he squats to defecate; dirty, cowed teachers with accusatory boards hanging from their necks. At times it's grim, at others funny. "Comrade, don't you realise," the po-faced children tell a baffled restaurateur. "These are reactionary dishes! You'll have to change the whole menu!"

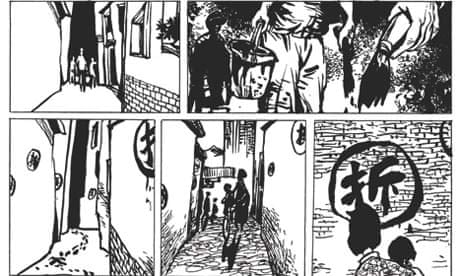

As Li grows, his skill at drawing is spotted: he gets an art teacher, whose pious canvases of Mao cover paintings of nude women, and is later invited to work for a provincial paper. It's easy to see why he was noticed. A Chinese Life's black-and-white artwork is dominated by vibrant images of jostling crowds, leaping children and heaving markets, their urgent life interspersed with sculpted propaganda portraits, beautifully still landscapes and fantastical visions. Li is less interested in character – his faces are often rendered so simply as to feel anonymous – than in backdrops: the roofs and windows of rural settlements, the skyscraping urban landscapes, or tree stumps pointing fruitlessly into the gloomy sky.

The narrative loses some of its focus as it enters the modern age, where the now-established artist charts the successes and the flaws of entrepreneurial China. Here Li darts between massage parlours, flash restaurants and remote villages in an approach that can feel contrived. It's a shame, meanwhile, that Li's touching relationships with his parents, and his briefly sketched marriage aren't given more time.

Yet A Chinese Life remains richly rewarding. Li's loyalty to the party, whether embodied by Mao's teachings or Deng Xiaoping's reforms, rarely wavers, and that in itself is fascinating. The book never mentions Tibet, and barely touches on Tiananmen Square; he knew no one there, explains Li, and anyway, having seen the effects of "invasion, plunder, unequal treaties, internal divisions, battles among warlords", he believes China needs order and stability first: "the rest is secondary".

This is no definitive account of modern China. It won't tell you much about policy decisions, power struggles, or almost anything Li didn't himself witness. If it did, its scope would be mind-boggling. Instead, its tight focus gives you a wonderfully immediate sense of how one man was shaped by modern China, and the agonising struggles that took place around him.

This ambitious graphic novel pulls you to the chest of the world's latest superpower, shows you something of what it has gained and lost, and lets you go, 60 years later, drained and intrigued and feeling as though you know China's great, tangled present a little bit better.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion