The Pakistani city of Lahore is one of the Indian subcontinent’s most brilliant gems, yet it remains relatively obscure outside the country – an unexpected pleasure for travelers.

With Pakistan enjoying improved security, visitors are starting to rediscover the city’s treasures.

“Pakistan finally seems to be emerging from the shadows, back onto the tourist map,” says Jonny Bealby, founder of Wild Frontiers, a tour operator based in the UK and US that has been running trips to Pakistan for 20 years.

“And Lahore is a major player in this transformation,” he adds. “As one of the most historically rich, and culturally important cities on the whole of the subcontinent – yet without the curse of mass tourism – it represents one of the most exciting and vibrant travel destinations in the region.”

Lahore has a grand history. By the 17th century it was famed as one of the world’s most populous and cultured cities. Its overlords, the Mughals – a Turkic dynasty from Central Asia that established its rule on the Indian subcontinent in 1526 – were a byword for power and opulence.

That golden age blessed Lahore with more Mughal architectural masterpieces than either Delhi or Agra. Today, the city is Pakistan’s main bastion of history, culture and cuisine.

Lahore is the capital of the central-eastern province of Punjab. It lies near the crumbling mud banks of the Ravi River, 15 miles from Wagah, the border crossing with India, where turbaned guards from both countries take part in a daily foot-stomping ritual.

Here’s a guide to Lahore’s top five sights.

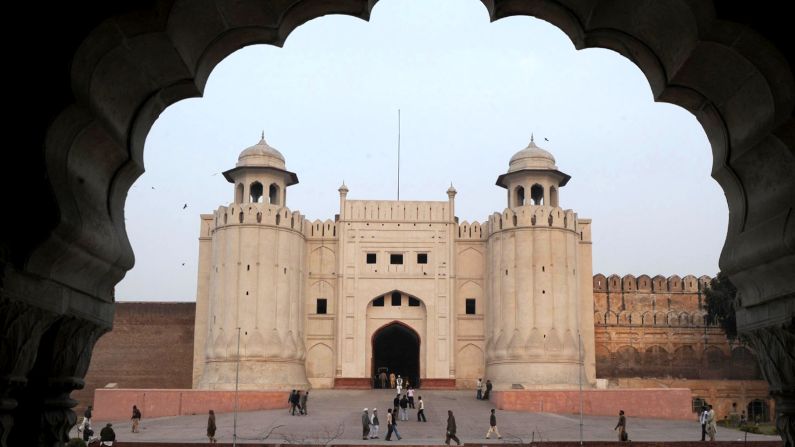

Lahore Fort

Akbar the Great built the fort in 1575 to quell rebellions on his empire’s northwest frontier, making Lahore his capital a decade later.

As you walk through the fort’s honeycomb of intricately carved arches, sandstone pavilions and palaces, you’ll be surrounded by the architectural style born in Akbar’s reign. It became the hallmark of Mughal culture – a fusion of Hindu and Islamic traditions, which reached its zenith in the Taj Mahal.

Akbar’s son, Jehangir, and grandson, Shah Jahan, lavishly developed his architectural idiom, adding palaces, towers and gardens to the fort’s 20 hectares. Their contributions have made the fort a trove of some of the Mughal world’s most outstanding designs.

See the angels and djinns on the tiles of the former’s Lal Burj (Red Tower), and the latter’s marble Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) and Shish Mahal (Palace of Mirrors), with its brilliant gilt work, pietra dura and carved marble lattice screens.

After dawdling among them, and stopping in the fort’s museum (which includes an excellent collection of Sikh artifacts and paintings), march down the steps of the mammoth Elephant Path and wander along below the camels, flowers and dragons depicted in the tile mosaics of Jehangir’s extraordinary Painted Wall.

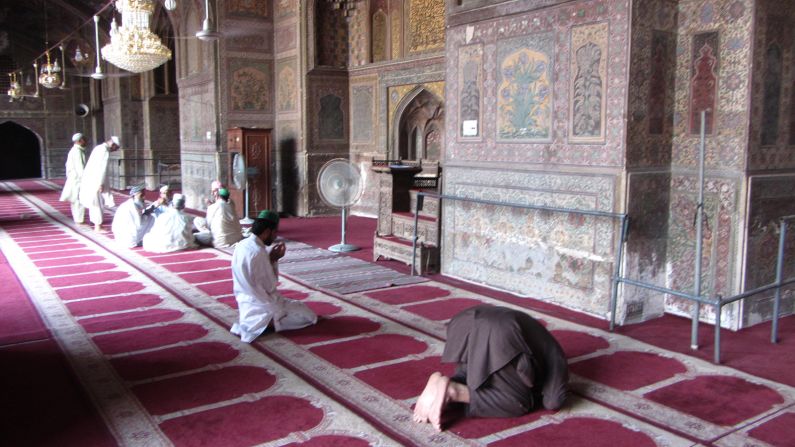

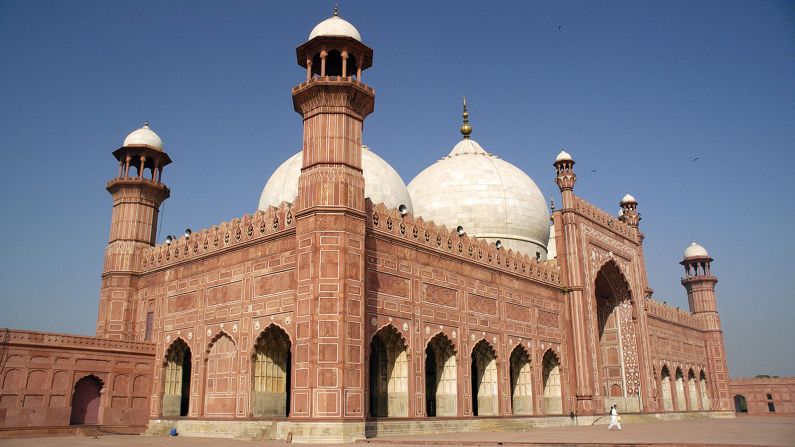

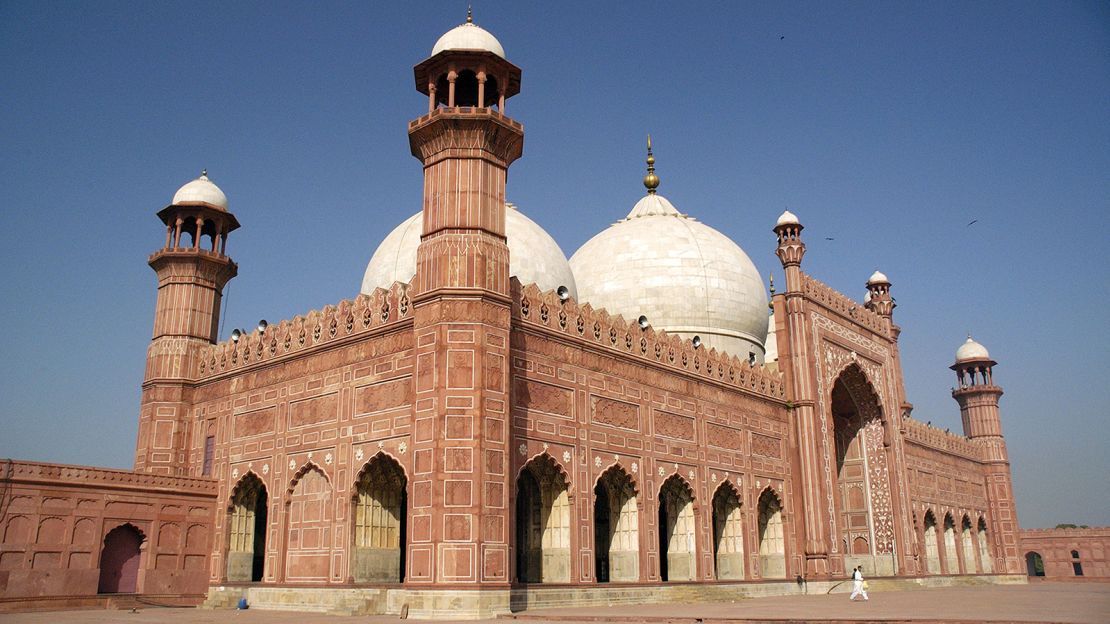

Badshahi Mosque

Pakistan’s most iconic building, the massive pink-red Badshahi Mosque, is a cannon shot away from the fort.

To enter it, climb the high steps up to a grand vaulted gatehouse, which leads into a vast arcaded courtyard, built to accommodate 60,000 worshippers.

Surrounded by merlon-capped walls embellished with stone carvings and marble inlay, the prayer hall lies across the courtyard floor under bulbous domes.

Emperor Aurangzeb built the mosque in 1674, to commemorate great victories in the south of his empire. According to another, less credible, local tradition, he built it to house a hair of the prophet Mohammed.

For centuries it was the world’s largest mosque. Today, it’s a monument to Mughal genius.

Its prayer hall is bright with elegantly restrained fresco work, stucco tracery and columns, which appear as vases containing decorative flowers in relief.

This radiance continues throughout the hall’s domed chambers, which, divided by pointed arches, have extraordinary acoustics – a large factor in the mosque’s atmosphere of clarity.

Some of the city’s later rulers didn’t see the mosque in such glowing terms, however. Sikhs and British commanders used it for stables and storing munitions.

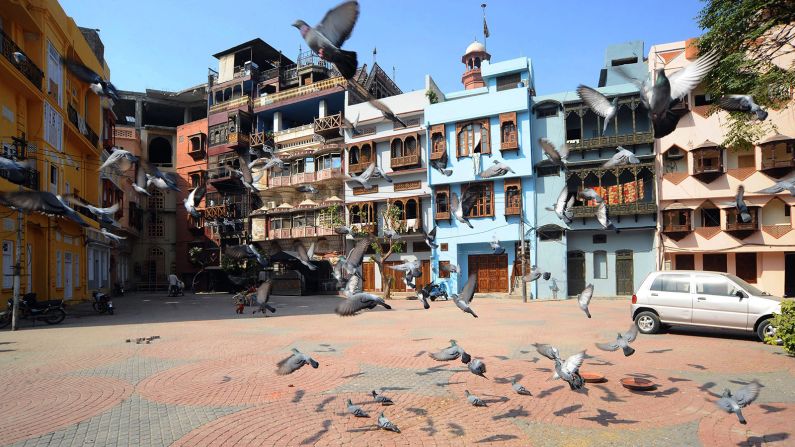

The Old City

Next to the fort and Badshahi Mosque, the Walled or Old City is a sprawling warren of bazaars divided into large quartiers of formerly glorious, now decaying old townhouses.

It’s a real maze so pick up a guide for the walking tour (the Walled City of Lahore Authority organizes tours on several routes), which starts at the Delhi Gate, one of Lahore’s half dozen surviving gates.

Near the gate is a magnificent, freshly renovated Mughal hammam, or Turkish bath (sadly not working). From there you’ll plunge straight into the colourful chaos of the Kashmiri Bazaar.

Immediately, you’ll see recent efforts to renovate the Old City. Several alleys have been tidied up, electricity wires buried and sewage troughs covered.

Walking out of the Kashmiri Bazaar you’ll come to the Old City’s most famous treasure, the technicolor 17th-century Wazir Khan Mosque, newly renovated and radiant.

Its magical exterior and interior tile and fresco work exude refinement. Rudyard Kipling described it as “full of beauty even when the noonday heat silences the voices of men and puts the pigeons of the mosque to sleep.”

From here walk westwards towards the Sunehri Masjid (Golden Mosque), near several of the Old City’s best bazaars, where you can wander for hours.

In the Azam cloth market, you’ll pass stall owners doling out some of the Old City’s famous dishes: Thick daals, kebabs, kidneys, trotters and battered fish simmer in skillets.

A very worthwhile detour, southwest towards Bhatti Gate, through more of the labyrinth, in the Hakiman Bazaar, is the private Fakir Khana Museum. Admission is free but telephone (+92 321 7450598) ahead to make an appointment.

For a rest, head back towards the Badshahi Mosque to Cuckoo’s restaurant. Its owner, the artist Iqbal Hussain, was born in this district, Heera Mandi (literally “Diamond Market”), a famous, now dying red-light area.

The restaurant’s rooftop terrace provides the best view of the Badshahi Mosque — its minarets looming above.

Kim’s Museum

To see one of the best examples of how the British Empire period influenced the city’s architecture, head along the Mall Road to Lahore Central Museum.

In front of it, on a traffic island in the middle of the road, stands the fabled 18th-century cannon, Zam-Zammah (Urdu for lion’s roar).

It is immortalized in the opening scene of Rudyard Kipling’s novel “Kim,” which begins with the young adventurer sitting “astride the gun Zam-Zammah on her brick platform opposite the old Ajaib-Gher, the Wonder House, as the natives call the Lahore Museum.”

Kipling’s father was the museum’s chief curator for 18 years. As you enter the cavernous museum through a vestibule with a high frescoed ceiling and come upon its musty clutter of artifacts, you may share the sense of wonder that John Lockwood Kipling imparted to his son.

You’ll be among treasures of the Indus Valley Civilization and Buddhist antiquities from Gandhara, a Silk Road kingdom centered on what is now Peshawar.

Look out for one of the museum’s most famous objects, The Fasting Buddha, which is included on the Unesco World Heritage list.

The museum also has wonderful rugs, glazed tiles, votive paintings, and a main gallery filled with Persian and Mughal miniatures.

To see a characteristically glum statue of Queen Victoria, go to the Museum’s exhibition of Pakistan’s recent history, which focuses on the tragic events surrounding Partition in 1947, when the country was created.

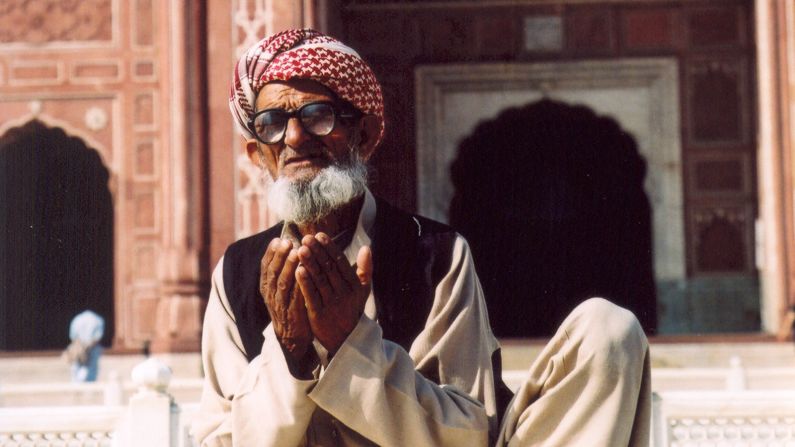

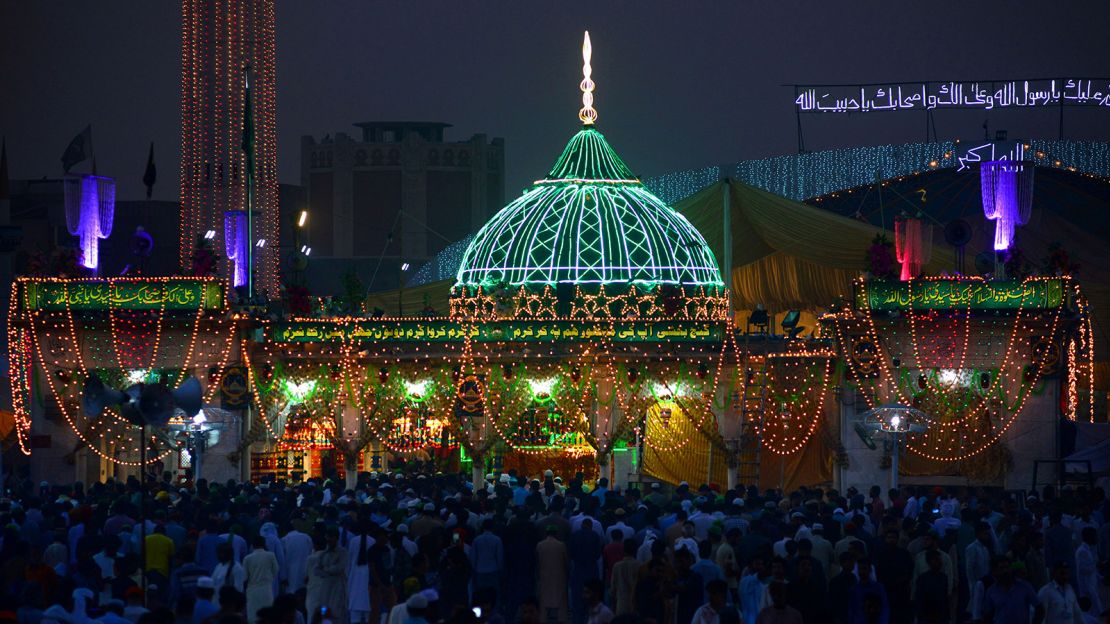

The Shrine of Data Ganjbaksh

To get to the city’s heart, go just before dusk to the shrine of the 11th-century mystic Data Ganjbaksh (‘Lavish Giver’), not far from the museum and the Old City.

The saint lies under a raised, plastered mound in the shadow of a tall headstone. His tomb is usually draped with brocade and embroidered shrouds, overlain with strings of pearls and yellow and red petals.

Data sahib, or more formally Abul Hasan Ali ibn Uthman al-Jullabi al-Hujwiri al Ghaznawi, was one of the earliest of the Sufimystics who contributed to the spread of Islam on the Indian Subcontinent.

Emperor Akbar, who embraced a medley of rituals and beliefs from different religions, built the shrine’s original compound. Other rulers have since cashed in on the saint’s popularity by embellishing it with minarets.

But the spirit of the saint prevails. Here, you can experience up close the jostling and joyful celebration of Pakistan’s most popular Muslim traditions.

If you have time before leaving Lahore, you might reach two more Mughal wonders: the spectacular Shalimar Gardens and Tomb of Jehangir, where locals play cricket and badminton, seemingly oblivious to the mausoleum’s magnificence.