Analia Saban paints a different picture of success

Analia Saban went to art school at the height of the recent market boom, when it was not uncommon for students, particularly in UCLA’s prestigious painting program, to be fielding offers from galleries and selling work directly out of their studios. It had a significant impact on the direction of her career, though not because she profited by it at the time.

Indeed, she had a rough go of it. Raised in Buenos Aires, she came to Los Angeles in 2002 by way of a small college in New Orleans, where she studied video art primarily. Enrolling in UCLA’s New Genres program — the “outcast” cousin, she jokes, to painting and sculpture — she was younger than most of her peers, with a less formulated notion of where she was headed, and for the first two years she produced very little.

“Some of my classmates were selling already a lot of work and I was just surviving,” she says. “It wasn’t easy.” In the third year, however, something clicked. “I began to wonder,” she recounts, “why were my classmates in the painting department doing so well and I wasn’t? What is it with painting? What is painting, anyway?”

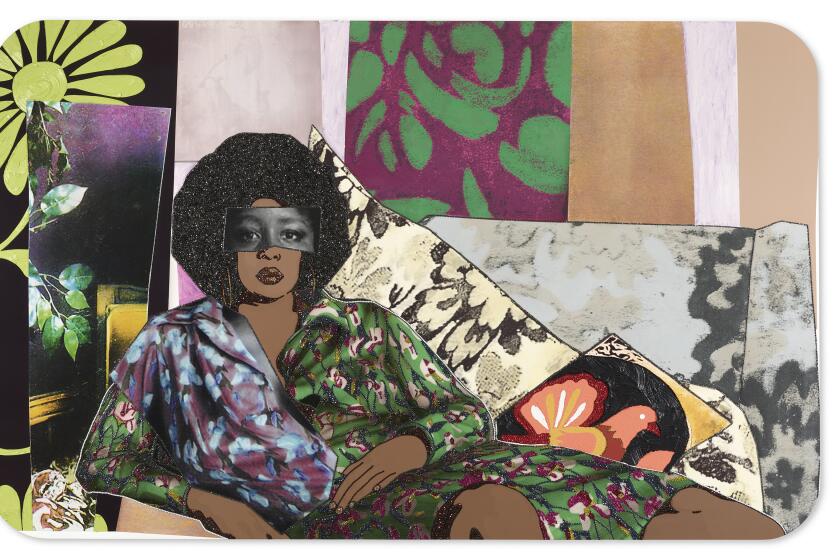

It’s a question that’s driven her work ever since. She didn’t become a painter; rather, she began to take painting — and later photography, sculpture and print-making — apart, often literally. For her thesis show, she acquired paintings and carefully unraveled them, then reassembled the threads into objects: a scarf; a woven tapestry mounted — with a smirk, clearly — onto canvas; giant balls of wound thread. (The title of one 26-inch ball: “48 Abstracts, 42 Landscapes, 23 Still Lives, 11 Portraits, 2 Religious, 1 Nude.”) She “reinterpreted” Picasso’s “Guernica” by disassembling a replica and arranging its parts — stretcher bars, braces, a ball of unraveled canvas thread — in shape-specific piles on the floor. Later, she produced her own generic brush strokes by painting with acrylic onto plastic wrap and then taped, sewed or draped them onto canvases.

“Usually we think of painting on canvas,” she says. “It was interesting to think of painting as pigment on thread. To look at it as if I were an alien or something: What is this thing? On the microscopic and macroscopic levels.” Of the removable brush strokes, she says: “It was interesting to see them as tiny little sculptures. Having space between the brush strokes, I could really see how a painting worked. You could get on the side and see the building of the image.”

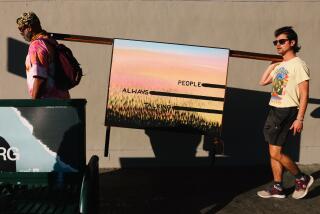

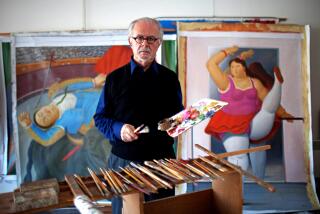

Modest, soft-spoken and slight of frame, with a faint Argentine accent, Saban, 31, speaks of her work with the cautious enthusiasm of a research scientist. The Santa Monica studio in which she lives and works was passed on to her by John Baldessari, her former teacher and onetime employer, whose traces remain visible throughout the space, most conspicuously in the form of a pair of handprints set in a patch of recently laid concrete. The live-work arrangement tips toward work from the look of it: a large, squarish space with one corner partitioned off for sleeping and most of the rest given over to works in progress, materials and tools.

On any given day, multiple “experiments” can be found around the studio in various states of completion. For one series, she’s scraped pigment from the surface of black-and-white photographs, then smeared it onto adjacent canvases or sheets of drawing paper to produce strange and stark abstract compositions. For another she’s used a laser cutter to cut every letter of text from individual sheets of newspaper, then put each sheet through a screen printer with blobs of ink behind it so the ink seeps through and often violently rips the text as it is flattened by the press. Excitement dispels her shy manner as she discusses the process of each work in detail.

When asked, however, whether there are experiments that haven’t worked, she replies: “Oh, I go through so much failure. A lot of people say, ‘Be excited, that is part of the process.’ But when I’ve just spent $500 in silicone and it went into the trash — then it’s not so fun. It’s important to go through that, and over time things come together. But yes, a lot of failure.”

She’s put canvases into clear plastic bags, filled them with paint and sealed them, ensuring that the paint remains wet. (“I feel like the viewer never gets to see wet paint,” she says.) With others, she’s left the bag open, let the paint dry, then peeled the bag away to produce a canvas with a wide, smooth bulge across the bottom. Through the fall, she was working on latex casts of terry-cloth towels, which she used to reproduce the towels in white, acrylic paint, which she then draped or pinned to raw canvases. She made a similar series using plastic bags, slipping canvases into the newly cast bags and exhibiting them on the floor, leaning against a wall.

“It’s made like a sculpture,” she says of one of the casts, “which is something that’s interesting to me. It’s the process of sculpture applied to a painting.”

The success that her painting classmates enjoyed at UCLA has come round to her in due time as well. On a studio visit one afternoon last fall, she had two assistants alongside her to complete work for three successive solo shows — in Paris, Buenos Aires and Art Basel Miami Beach. The cast bags and towels she showed in Miami (with Thomas Solomon Gallery, her primary dealer). It was a subtle though distinctly cheeky gesture, characteristic of her rigorously playful sensibility: conflating the hallowed sophistication of Minimalist painting with the poolside hotel consumerism of the art fair, while somehow avoiding the didacticism of parody and preserving a degree of elegance.

“I feel like I’m trying to revisit some clichés of painting,” she says. “Even some of the beautiful moments, like Minimalism. But also with a sense of humor.”

More to Read

More to Read

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.