Windows 10 S is going to piss a lot of people off. In fact, it has already started to piss some of them off, and they've been annoyed by it since the first leaks about the operating system came out.

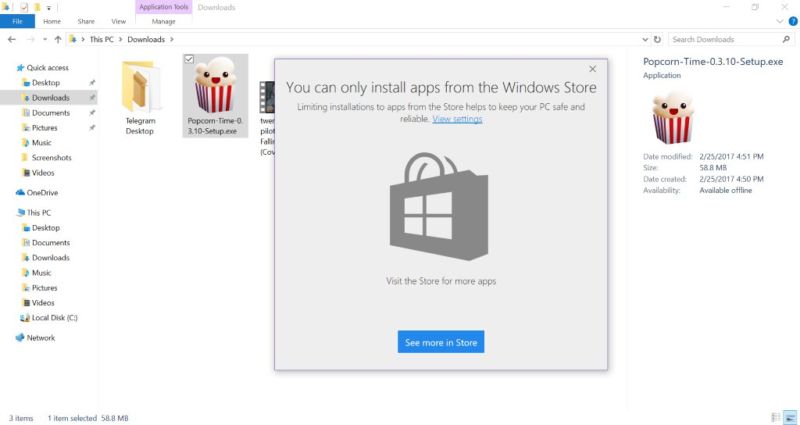

The arguments are well-worn, and we've been hearing them ever since Apple opened the App Store for the iPhone. Windows 10 S blocks the execution of any program that wasn't downloaded from the Windows Store. Arbitrary downloaded apps, or even apps with physical install media, are forbidden, a move that on the one hand prevents running malware but on the other blocks the use of most Windows software. Windows Store apps include both tightly sandboxed apps, built using the Universal Windows Platform, and lightly restricted Win32 apps that have been packaged for the Store using the Desktop App converter, formerly known as Project Centennial.

This positions Microsoft as a gatekeeper—although its criteria for entry within the store is for the most part not stringent, it does reserve the right to remove software that it deems undesirable—and means that the vast majority of extant Windows software can't be used. This means that PC mainstays, from Adobe Photoshop to Valve's Steam, can't be used on Windows 10 S. It also means that Windows 10 S systems can't be used to develop new Windows software. Should you want to run this kind of software, you'll need to upgrade to the full Windows 10 Pro for $50.

Some of the arguments against this are bizarre. Notably, the complaint that Microsoft has now erected a paywall—"you have to pay $50 to run Steam!"—is very peculiar when one considers that, in general, Windows licenses have never been free. While Microsoft has offered OEMs free licenses to try to stimulate adoption of Windows in certain markets, in general cases someone has to pay: either for a retail license in a boxed copy or for an OEM license that's pre-installed. So while the complaint that Windows software is behind a paywall may be true, it's something that has been true for literally decades. Windows has a cost, and if you want to run Windows programs, you have to pay the price. To the extent that this is an argument against Windows S, it is an argument against any and all paid software.

I also feel it's implausible that Microsoft will one day remove this ability to run traditional Windows apps sourced from beyond the Store. One could imagine that this might become disabled by default—in much the same way that Android defaults to only supporting apps from the Google Play Store but has a simple switch to unlock it—but the core ability is too fundamental to discard. Somebody needs to be able to develop those Store apps, after all. And there's too much legacy software, particularly in the business world, that will probably never find its way to the Store. Microsoft will forever need to sell an operating system that can run any Windows app.

In spite of this, Windows 10 S is already being attacked, heralded as the beginning of the end for Windows and an unjustifiable loss of control. Why would Microsoft make such a move? According to critics, it's not for any reason that benefits Windows users, but rather so that the company can enjoy the riches that come from taking a 30-percent cut of everything sold through the Windows Store.

The Windows Store makes bad parts of Windows better

I'd argue, however, that Windows users should want Windows 10 S to succeed. Windows 10 S isn't for everybody, and Windows 10 S may not be for you, but if Windows 10 S succeeds, it will make Windows 10 better for everyone.

The biggest practical problem with Windows 10 S right now is that Store dependence. Not because of any philosophical objection to Stores, but because the Store doesn't have a great many apps in it. In this way, Windows 10 S resembles Microsoft's previous attempt to create a Store-only device; Windows RT. There were vanishingly few worthwhile apps to run on Windows RT, and that was one of the chief reasons the operating system failed in the market.

But the Store in Windows RT required developers to write their apps from scratch. With negligible numbers of users, developers were uninterested in doing this work. The Store in Windows 10 has Centennial. In principle, Centennial should make it easy to package existing Win32 apps and sell them through the Store, and if developers of Windows apps adopt Centennial en masse then the Store restriction shouldn't be particularly restrictive.

Widespread adoption will be good for Windows users of all stripes. While many Windows users will say they want the freedom and flexibility to install anything from anywhere, the lived experience of this often leaves a lot to be desired. Applications routinely don't install or uninstall cleanly, leaving scattered remnants of their existence on your system. Apps with complex dependencies will often leave those dependencies in place when you uninstall, or they will sometimes remove those dependencies even though other apps still depend on them.

Application maintenance is also annoying. Some apps will install background services to update themselves; others will check for updates when you run them and ask to be updated. Some apps will install entire other apps just to handle updating. And plenty of apps still don't bother to include any good way of updating themselves at all, so you'll only get newer, better versions if you proactively go out looking for them.

None of this is actually very good. Windows users might tolerate this in the name of freedom and flexibility, but it's objectively crap. There's no virtue to these inconveniences. They're just annoyances, a consequence of different developers having their own taste and preferences.

The Windows Store, even for Centennial apps, provides a good solution. Windows Store apps install and uninstall cleanly. They can't do things like install services in the background or install dodgy device drivers (as many games have done, for copy protection); they can't mess with shared dependencies; they won't leave files scattered around your hard disk or configurations spread through your registry. Moreover, the Windows Store provides a common and consistent update system, so instead of a half-dozen apps using a half-dozen different updaters, there's just one updater—the Store updater. Many times over the years we've heard Windows users say they wish that third-party apps could update with Windows Update; that's more or less what the Windows Store offers.

Regardless of the kind of Windows user you are, these are desirable features. Most Windows software would be better if it were available from the Store. But most Windows software is not available through the Store, forcing us to use the mess of bad installers and bad updaters that dominate.

Chicken, meet egg

As Petri found when it surveyed a bunch of app developers, application developers for Windows aren't putting their apps in the Store, because they're not seeing a whole lot of interest in the Store. Packing an app with Centennial does require some amount of effort on the developer's part, and this forces them to ensure that their app doesn't do any of the things that Centennial doesn't allow.

One thing we've heard from devs that have used the Store is that it's actually pretty useful; the Store provides good information on things like usage levels and crashes, and it offers a feedback channel with ratings and comments. This can give the developers insight that they might not otherwise have.

It's not entirely surprising that Windows 10 users aren't calling for developers to use the Store, either. While Windows 10 does try to promote the Store, the advantages aren't particularly well understood or promoted. The Store hasn't entered their consciousness as a place to acquire applications, and the paltry selection of good apps in the Store isn't doing much to change their minds.

Microsoft is doing its part to improve the application selection, as it will soon be offering the Office desktop apps to the Store (using Centennial) for anyone with an Office 365 subscription. It would be great if Redmond could similarly get companies like Adobe to support the Store, but that's not an entirely straightforward prospect. Adobe has its own subscription service, Creative Cloud, and isn't likely to want to give up a share of the revenue just to be in the Store. Microsoft would do well to relax its revenue and billing requirements to ensure that developers like Adobe can use the Store without losing a cut; it would make the Store a much more credible source of Windows apps.

But the real drive has to come from users, and this is why Windows 10 S is so important. If Windows 10 S succeeds, there will be a much greater body of people asking developers to provide their apps through the Store. If, in turn, developers respond to this demand and do the work to port to Centennial, every Windows user will be able to take advantage, and Windows will be better for everyone.

Listing image by Microsoft

reader comments

427