I wrote Splendour on the eve of the new millennium. The whole decade, from the late 1980s onwards really, had been a period of huge political unrest. The play is set in an unknown eastern European city over the course of one night. There are four female leads and, as the evening progresses, you work out that one of them is the wife of a dictator. She is waiting for her husband to come home because he’s about to do a very important interview and have his portrait taken by a war photographer. But then she realises he isn’t coming back.

As the night unfolds, it transpires that not only has her husband left her, but the country is on the brink of revolution, one that’s going to wreak bloody revenge. You soon realise that you’re watching the last night of her life.I drew a lot of this from Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime in Romania. I was also haunted by the Bosnian conflict. I wrote the play in three days flat, without stopping. It was like doing a tapestry: I couldn’t put down the thread, because I was worried I’d lose my way. I had seen Bosnian and Kosovan refugees and immigrants around me in London, and I suddenly felt very angry about the architects of the era’s atrocities. I couldn’t figure out how so few people could hold so much power.

I then started to look at the women behind all these strong men. I was particularly fascinated by Hillary Clinton, whose husband was US president until 2001. As I worked my way back through all those first ladies, I realised that behind every powerful man, there is often a powerful woman.

I’d watched footage of Ceaușescu and his wife, Elena, in the moments before they were executed. It’s terrifying. They cower together like two little animals. Yet there is also huge defiance and anger, particularly from Elena. When I read about the execution, I found out that they were shot by their former guards. There were only two or three bullets in Nicolae’s body, but there were infinitely more in Elena’s. That was interesting: we feel huge anger towards those dictators, but even more towards those wives who stand by in the background. I carried that fury into the play.

Splendour is about the architects of history. There’s the dictator’s wife, Micheleine. There’s the person who stands by and watches and does nothing, in the form of Genevieve, the best friend who Micheleine rings up and asks to come round. There are those who observe and comment on dictatorships, like the war photographer. And there are those who are forced to collude and collaborate – in the form of Gilma, the interpreter. For me, it was about how we all respond, collude and pay witness to these moments in history.

I was living on my own when I wrote the play. I hadn’t had children yet, so had the luxury of writing day and night, sustained by a lot of chocolate and tea. Splendour reflects a kind of youth, energy, commitment and belief that I don’t have in the same way any more. I remember when I finished it feeling an overwhelming sense of having harnessed something. I find stage plays incredibly difficult to write, which is why I don’t do them very often these days. Of all the mediums, theatre is the one where you really need to have something to say – because it’s just you, the words and the space. The older I get, the more I have to think long and hard about what I need to say and why.

Splendour broke through to new territory for me. It exposed my commitment to writing for women, my desire to recognise that they can be as aggressive, violent, mercurial and complex as men. I think of it as a piece of music, my minor symphony. It has a bold, back-and-forth repeat structure because I was fascinated with retelling a moment from different perspectives. It opens with a vase breaking and that moment is repeated again and again. That motif is important: it’s a navigational point that keeps bringing the women back to that event. The shattering of the vase is really about the shattering of artifice. It also breaks the fourth wall because characters talk directly to the audience without anybody else on stage being able to hear.

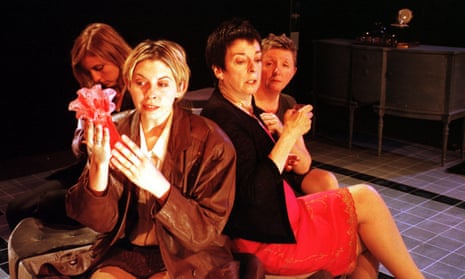

Splendour was first performed at the Edinburgh festival in 2000 by the Paines Plough company. It was incredibly exciting. I remember it all as the time just before my life changed. It was just before I met my partner and fell in love, just before I had my first child – a giddy time of late-night conversations and running around Edinburgh with Vicky Featherstone, then the artistic director of Paines Plough, now at the Royal Court. We were tipping into the noughties, high on freedom and experimentation.

Whether you’re writing for stage or screen, what’s fantastic is seeing your work adopted and raised by other people. The collective embraces it. As somebody who is really quite a neurotic loner, I find it hugely affirming to have a team around me believing my work is good. Seeing that play up and running was amazing: it was the first time I thought I could really make a career out of my passion.

Life experiences inherently change you as a writer. My sense of fury calmed down when I had children and found a loving partner. But I’ve started to feel that anger again recently – and the stage is the best place to express it. To be specific, the play that I’m focused on at the moment is about that abuse of power within Hollywood and within my own industry.

I suppose, more than anything, the reason that Splendour is so important to me is that I’m proud of my writing – which is unusual for me because I’m constantly critical of my voice. I was learning my craft, exploring form – and I had courage. It had been a difficult decade. I’d found it hard to survive in London and believe in myself as a writer at a time when everyone I knew was becoming a doctor or a barrister and buying a home and getting married and having babies. They were having a life and I was stuck living in a room in the middle of nowhere.