Written in Knots: Undeciphered Accounts of Andean Life

“Es cosa de admiración ver las menudencias que conservan en aquellos cordelejos, de los cuales hay maestros como entre nosotros del escrebir.” (Sarmiento de Gamboa 1942 [1572]: 34)

“It is a thing to be admired to see what details may be recorded on these cords, for which there are masters like our writing masters.” (Sarmiento de Gamboa 1999 [1572]: 41)

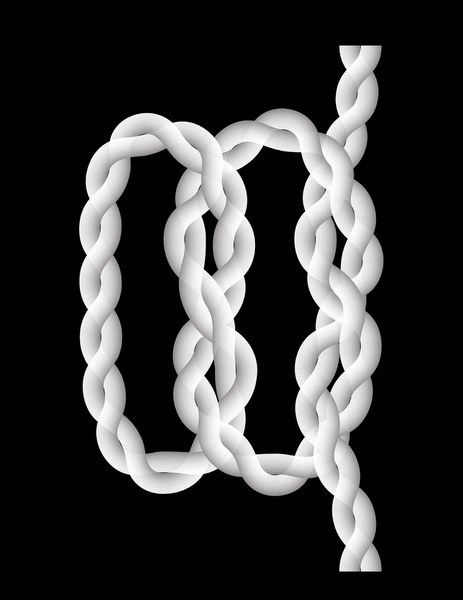

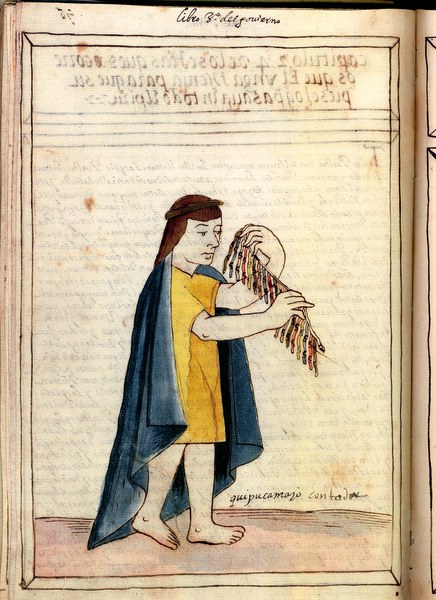

The environmental and altitudinal extremes of the Central Andes present innumerable challenges to its human and non-human inhabitants. And yet, numerous groups of people have called the region home, from the early hunter-gatherers and farmers to the Inka (1450–1534 CE), whose empire, known as Tawantinsuyu, was the largest ever established in the Americas. Arising in fewer than 100 years, Tawantinsuyu (meaning the land of the four quarters) was comparable in size to that of Rome on an infrastructure of roads, bridges, way stations, and warehouses designed to move people, products, and information from one end of the mountainous empire to the other within a matter of days. Incredibly, all this was achieved without the use of iron, the wheel, markets, money, or a written language. Benefiting from a wealth of technical, social, cosmological, and cultural knowledge from previous Pre-Columbian cultures, particularly that of the Wari (600–1000 CE, the first Andean empire), the Inka most likely inherited a sophisticated device known as the khipu (or quipu, “knot”)—consisting of multiple colored, twisted, and knotted cords—to record and convey information across both time and distance.

The exhibition was on view in the museum was on view April 2–August 18, 2019 and was curated by Juan Antonio Murro, Assistant Curator of the Pre-Columbian Collection, with Jeffrey Splitstoser, PhD, an expert on Wari khipu and ancient textiles and Assistant Research Professor of Anthropology at George Washington University. Find out more on the exhibition page.

Exhibition Images Catalog Videos