Attention

Dogs Use Various Gestures to Get What They Want From Us

New study shows dogs use referential signaling to communicate their intentions.

Posted May 29, 2018

Dogs have formed unique relationships with humans, due to their close association with us as they became the nonhuman animals (animals) we know today. Just about everyone who's shared their home with a dog knows they use a variety of signals and gestures in their interactions with us to draw our attention to specific objects, individuals, or events, often to try to get what they want. Despite "common knowledge" and some "citizen science" about how dogs communicate with us, very little is known about whether these gestures actually function as what researchers call "referential signals." But now, a new study that is available online by Hannah Worsley and Sean O’Hara called "Cross-species referential signaling events in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris)," published in the journal Animal Cognition, shows they do. Because the research paper is available, here's a summary of what the researchers discovered. A popular account of this study can be read in an essay by Linda Case called "Get Help! Pony is in Trouble!" I highly recommend Ms. Case's summary, because the research paper will require a good deal of time and knowledge of data analyses and statistics that might go beyond the expertise of many people who will be interested in the results. This is not a criticism of the essay or of readers, but rather recognition of the care and detail with which the study was conducted.

Referential gestures are behavior patterns that are intentionally used to direct a recipient's attention toward something, including specific objects, individuals, or events. Worsley and O'Hara note that for a gesture to be considered referential, it must have five features:

"First, it must be directed toward an object or specific area of the signaler’s body...Second, it is a mechanically ineffective movement...Third, it is aimed at a potential recipient and fourth, receives a voluntary response from that recipient...Finally, a referential gesture must also demonstrate hallmarks of intentional production." 1

Concerning the intention of a signaler to communicate with another individual, there also are five attributes, including that it must be goal-directed — if the individual doesn't get what they want, the gesture or other gestures must be repeated ("a process referred to as persistence and elaboration") — and it must be directed to an audience.

Methods of study, data analysis, and results

Worsley and O'Hara studied 37 domestic dogs (16 females and 21 males, 1.5 to 15 years old), all of whom had lived with their humans for at least five months before the study began. Employing methods of "citizen science," used by dog researchers Alexandra Horowitz and Julie Hecht in their study of play behavior, the researchers asked the dogs' humans "to film their dogs performing ‘everyday’ communicative bouts (e.g., requesting food and doors to be opened, playing and requesting to be scratched), using their mobile phone whenever the behaviors occurred."

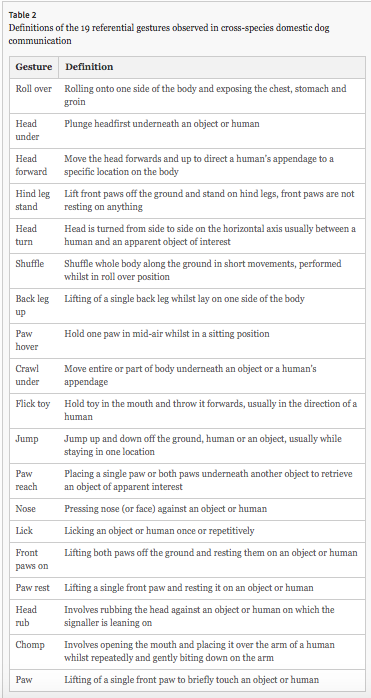

After data were collected, films were analyzed, and "Gestures were categorized as per their apparent satisfactory outcome (ASO). ASOs are deduced from a plausible desire and signaler satisfaction (Hobaiter and Byrne 2014). They produce an outcome that results in the termination of communication." All in all, the researchers discovered that 19 (1,136 instances) of 47 potential referential gestures satisfied the five requirements for them to be called referential signals (Table 2 above).

The four requests that were most commonly used that resulted in dogs being satisfied (ASOs) accounted for 242 bouts of communication and included: “Scratch me!”, “Give me food/drink," “Open the door, and “Get my toy/bone.”2 The most common gesture that was observed 381 times was gaze alternation (head turn). Thirty-five of the 37 dogs were observed to use it.

Within-species referential communication is very rare and has been observed in some great apes, birds, and fishes. Cross-species referential gesturing is even rarer. Linda Case writes, "While we have known for a number of years that dogs are uniquely capable of understanding human communication signals, this is the first study to demonstrate that dogs use a diverse set of referential signals when they communicate with us and that, just like our dogs, we understand what they are telling us. This is cool stuff."

Ms. Case is correct, and I hope that in the future I can write more about referential communication not only by our canine companions but also by other animals. Hannah Worsley and Sean O’Hara's seminal study opens the door for further studies of the cognitive abilities of dogs, and it's well-worth reading and studying the many summary tables they provide. The bottom line is that we must pay careful attention to the ways in which dogs "talk" to us and ask us to do things for them. They know what they want and are pretty good at telling us — we just have to watch them carefully so that we fulfill their desires. When we do, it's a win-win for all.

Notes

1Here is a summary from Linda Case's essay "Get Help! Pony is in Trouble!"

For a gesture to be considered referential, it must possess these five attributes:

- It is directed towards an object or an objective (Pony).

- It is mechanically ineffective (Ally running from Mike to Pony cannot save Pony).

- It is directed towards another individual (Mike).

- It results in a voluntary response by the receiver (Mike saves Pony).

- It has intention (Obviously, Pony is in trouble and must be saved).

2In terms of what dogs ask for (and get), Linda Case writes, "The four most commonly used and most successful referential gestures were requests for petting/scratching, food or water, to go outdoors, and to retrieve a toy (Pony!)."

Facebook image: InBetweentheBlinks/Shutterstock