For decades, technology has relentlessly made phones, laptops, apps and entire industries cheaper and better—while health care has stubbornly loitered in an alternate universe where tech makes everything more expensive and more complex.

Now startups are applying artificial intelligence (AI), floods of data and automation in ways that promise to dramatically drive down the costs of health care while increasing effectiveness. If this profound trend plays out, within five to 10 years, Congress won't have to fight about the exploding costs of Medicaid and insurance. Instead, it might battle over what to do with a massive windfall. Today's debate over the repeal of Obamacare would come to seem as backward as a discussion about the merits of leeching.

Hard to believe? One proof point is in the maelstrom of activity around diabetes, the most expensive disease in the world. In the U.S., nearly 10 percent of the population has diabetes, around 30 million people. Within a decade, some experts say, the number of diabetics in China will outnumber the entire U.S. population. Most people who suffer from the disease spend $5,000 to $10,000 a year on medication, and diabetics with complications can spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on doctor and hospital bills. That and the lost wages of diabetics cost the U.S. alone more than $245 billion a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That's an enormous problem to solve — and a pile of potential cash and customers to be won—which is why diabetes is attracting entrepreneurs like ants to a dropped ice cream cone. One of those entrepreneurs is Sami Inkinen. He was a co-founder of the real estate site Trulia and has long been an endurance athlete, competing seriously in triathlons and Ironman events. In 2014, he and his wife rowed from California to Hawaii. None of this fits the typical profile of a diabetic, yet in 2011, soon after yet another triathlon, Inkinen was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. And like many driven, super-smart data geeks, he dove into research to understand everything about his condition.

That journey led him to Dr. Stephen Phinney, a medical researcher at the University of California, Davis, and Jeff Volek, a scientist at Ohio State. Phinney and Volek wrote two books together about low-carbohydrate diets and published scientific papers describing how constant adjustments to diet and lifestyle can reverse diabetes in many patients. Diabetes is almost never treated that way because the program is too hard for most people to stick to. It requires so much coaching and scrutiny by medical professionals, you'd pretty much have to hire a live-in doctor.

Inkinen convinced Phinney and Volek that technology could essentially re-create a live-in doctor and diabetes coach in a smartphone. Together, the three founded Virta Health in 2014. The company stayed in stealth mode until now, launching in March. "It felt like a duty to do this," Inkinen tells Newsweek . "Here is an epidemic of epic proportion, and nothing is working. We can combine science and technology to solve the problem at much lower cost and do it safely."

Here's how Virta works and why its approach is so important to the future of health care. On the front end, Virta is software on a smartphone. Diabetics who sign up agree to regularly enter data: glucose levels, weight, blood pressure, activity. Some do this by manually entering information; others use devices like a Fitbit or connected scales to automatically send it in. The app also frequently asks multiple-choice questions about mood, energy levels and hunger — more data that the AI software crunches to learn about the patient, look for warning signs and symptoms and guide Virta's doctors.

On the back end, Virta hires doctors who get streams of updates from Virta's software and use the data to help them make decisions about how to adjust each patient's diet and medications or anything else that might affect that person's health. "Any clinical decision is always made by a doctor," Inkinen says. "But the software increases productivity by 10-X." (That's 10 times, in Silicon Valley–speak.) When all this works and the patient follows the program's strict dietary and medical controls, diabetes can be reversed, clinical trials of Virta's system have shown. Around 87 percent of patients who had been relying on insulin to control their condition either decreased their dose or eliminated their use of insulin completely—a success rate that matches that for bariatric surgery, which is an expensive, invasive, last-ditch effort for severe diabetics.

Virta leverages AI software, smartphones and cloud computing to allow its doctors to continually interact with many times more patients than they can in a clinic or hospital, and it gives its diabetic patients a cross between a pocket doctor and a guardian angel. The result is a promising treatment for diabetes that could get many sufferers off medication and keep them out of doctors' offices and hospital emergency rooms. And that, in turn, would greatly lower the overall cost of diabetes.

Virta is just one startup of many attacking diabetes. Livongo is a more automated but less doctor-oriented version of Virta's program. The company, which raised $52.5 million in March, makes a wireless glucose-reading device that uploads the diabetic's data. AI software learns about the patient and sends a stream of tips and information intended to help the diabetic manage the disease and stay out of hospitals. Yet another new startup, Fractyl, takes a more medical approach. It invented a type of catheter that seems to cause changes in the intestines that result in reversing diabetes.

Startup tracker Crunchbase lists about 130 new tech-oriented companies (the number changes constantly) involved in some aspect of diabetes. While many of these startups will fail, it's hard to imagine that some won't have a significant impact.

These efforts matter to all of us because diabetes is such an enormous drain on health care resources. Venture capitalist Hemant Taneja, who helped start Livongo, says technology could take $100 billion out of the annual cost of diabetes in the U.S. Imagine if even 20 percent of diabetics could get off medication and have little need for a doctor's care. All of those medical resources would get freed up for other patients and other conditions, which should help lower prices of health care for all. "If we want to massively lower health care costs, we need to figure out how to address metabolic health issues [like diabetes] at their core," Inkinen says. "I would bet my house that in 15 years, the future health care company looks like what we're doing today—not treating diseases at the end of the road but catching them along the way and reversing them."

'Alexa, What's Wrong With Me?'

Over the past decade, medical records in the U.S.—long kept on paper in doctors' horrible handwriting—have been digitized and fed into software. That hasn't helped lower health care costs yet, and in fact it is adding to them as systems get installed and medical professionals learn to use software that can be clunky. Epic Systems, the biggest electronic medical records company, handles 54 percent of patients' records in the U.S. but gets bad marks for being so hard to use that it eats up doctors' and nurses' time. One report from Becker's Hospital Review said that almost 30 percent of Epic clients wouldn't recommend it to their peers. A survey by Black Book Market Research found that 30 percent of hospital personnel were dissatisfied with their EMR systems, with Epic getting the strongest dissatisfaction.

But there's a larger gain from the pain of EMRs: Enormous amounts of medical information are now digitized. As more medical interaction happens online—as with Virta or Livongo—the more kinds of data we'll collect. Internet of Things devices, whether Fitbits or connected glucose meters or potential new devices like Apple AirPods that take biometric readings, will add yet more data. All this data can help AI software learn about diseases in general, and about individual patients, opening up new ways for technology to be applied.

Some of the new applications of AI will simply improve a tragically inefficient health care industry. Qventus is a startup using AI to take all the data flowing through a hospital to learn how to free up doctors and nurses to see more patients and improve outcomes. "We're creating efficiency out of seemingly nothing," Qventus CEO Mudit Garg tells me. "Two years ago, work like this was so unsexy. But this is where the rubber meets the road."

One of his clients, Mercy Hospital Fort Smith in Fort Smith, Arkansas, has been able to treat 3,000 more patients a year with the same resources, an increase of 18 percent. Here again, technology is increasing the supply of medical services, potentially changing the cost equation that keeps forcing health care prices higher.

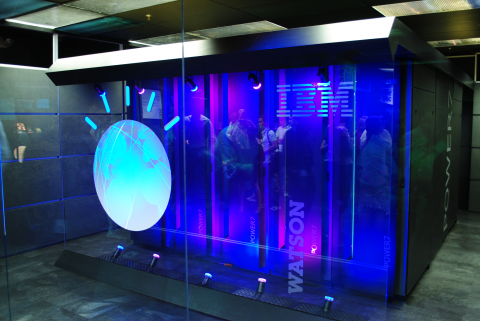

AI is also starting to automate some of the work of doctors. IBM's Watson, which uses machine learning and massive computing power to reason its way through questions, is on its way to becoming the best diagnostician on the planet. Its software can soak up all manner of available (and anonymized) patient data, plus the tens of thousands of medical research papers published every year (far more than any human could read). The system can even keep up with the news, learning, for instance, which regions are affected by a certain contagious disease, which might help diagnose someone who recently traveled to one of those areas. By asking patients a series of questions spoken into any kind of computer or connected device, Watson can quickly narrow down the possible causes of a medical problem. Today, IBM works on test projects with major hospitals like the Cleveland Clinic to put Watson in the hands of doctors, who are learning how to use the technology like a brilliant assistant.

But the day will come when Watson or something like it is available to everyone through a smartphone or some other device. Amazon is starting down that path by partnering with HealthTap to offer what it calls Dr. A.I. on Alexa, Amazon's voice-activated AI gadget for consumers. It's not nearly as robust as Watson but works on the same idea. Just tell it your medical problem, and it will ask you questions to help narrow down what it might be.

As health care AI develops, startups are also creating new kinds of genomics-based medicine. Just 16 years ago, the Human Genome Project and geneticist Craig Venter's startup, Celera Genomics, published the results of their human genome sequencing within a day of each other in 2001. Venter said his project took 20,000 hours of processor time on a supercomputer. This year, startup Color Genomics is offering a $249 genetic test that can sequence most of the pertinent genes in the human body. Color's goal is to make genetic sequencing so cheap and easy that every baby born will have it done, and the data will inform his or her health care for life.

Combine genetic data about a person with all the kinds of data Watson can ingest, and we're close to being able to build AI software that can at least supplant that first visit to a doctor when you're sick—which, of course, is when you least want to travel to a doctor's office. Instead, people will increasingly speak to a smartphone or to something like Dr. A.I. on Alexa about their health problems and, if necessary, send in photos of that rash or funky toe. If the system has your health care records and genetic data, it can gain more insight into your condition than any doctor operating on an informed hunch.

On many occasions, the app might tell the user the problem is nothing serious—a robot equivalent of "Take two aspirin and call me in the morning." Other times, the app might send the user to a clinic to get a test or X-ray. If that's how it plays out, a large chunk of the traffic into doctors' offices and hospitals will fade away.

Add it up, and in these next few years we're going to see a parade of tech applications that reduce demand on the health care system while giving all of us more access to care. Doctors should be freed up to do a better job for patients who truly need their attention. Theoretically, all of this will help keep more people healthier. And if we're all healthier and using health care less, the laws of supply and demand should kick in, sending the overall cost of health care tumbling.

However, there are bumps ahead because, as our erudite president recently said, "nobody knew that health care could be so complicated."

The Automation Rx

The economics of health care are weird. First of all, the usual forces don't apply to highly regulated industries, and health care is perhaps the most regulated in the U.S. and around the world because lives are at stake. In most countries, regulators prevent AI software from crossing the line into independently offering a diagnosis or clinical advice—that's strictly the purview of doctors. New medical devices, like Fractyl's, have to get approval from the Food and Drug Administration. Lobbyists often slow regulatory change to maintain the status quo and benefit incumbents charging inflated prices.

Personal health care decisions in the U.S. often get influenced by insurance companies, employers who pay for health benefits, and Medicare. Unlike most industries, consumers in health care don't have much information about pricing or quality, so they can't weigh options and make rational choices. Moreover, we think about health differently from anything else we buy. Many of us are never satiated with health care—we always want more and better health care, if we can afford it. One study published in March showed that telehealth —making doctors available by video call—prompted people to seek care for minor illnesses they otherwise would've ignored. Only 12 percent of telehealth "visits" replaced in-person visits, and the other 88 percent was new demand.

Until recently, most new medical technology has been high-end products that give doctors and hospitals a reason to charge more for something that couldn't have been done in the past. Think MRI machines or robotic limbs. These improve quality of life but add to costs. In 2008, the Congressional Budget Office concluded, "The most important factor driving the long-term growth of health care costs has been the emergence, adoption, and widespread diffusion of new medical technologies and services."

The next wave of health care technology is different. The combination of data and AI was not available until the past year or two, and it can lead to the kind of automation that has disrupted so many other industries. Many health care entrepreneurs are focused precisely on the win-win-win prospect of lowering the cost of care while making it better and available to more people. Of course, there will be challenges to address, such as making sure our highly sensitive medical data stays protected and private, even as it flies around various networks and systems.

As startups bring these technologies online, they're often doing an end run around insurance companies, instead finding demand among consumers or employers who offer health coverage. Livongo, for instance, points out to companies that each diabetic employee costs thousands of dollars a year in care. Pay for the Livongo service, the pitch goes, and your company will save money as those employees better manage their conditions. By last year, Livongo had signed up more than 50 large customers, including Quicken, Office Depot, Office Max and S.C. Johnson & Son. As the thinking goes among health care startups, once employers and consumers embrace new technology, insurance companies, regulators and health care incumbents will have to follow.

As that happens, the technologists promise, economic forces will finally stall or reverse the climbing cost of health care in the U.S. and around the world, a development that would, if we're lucky, leave the president and just about every member of Congress speechless.