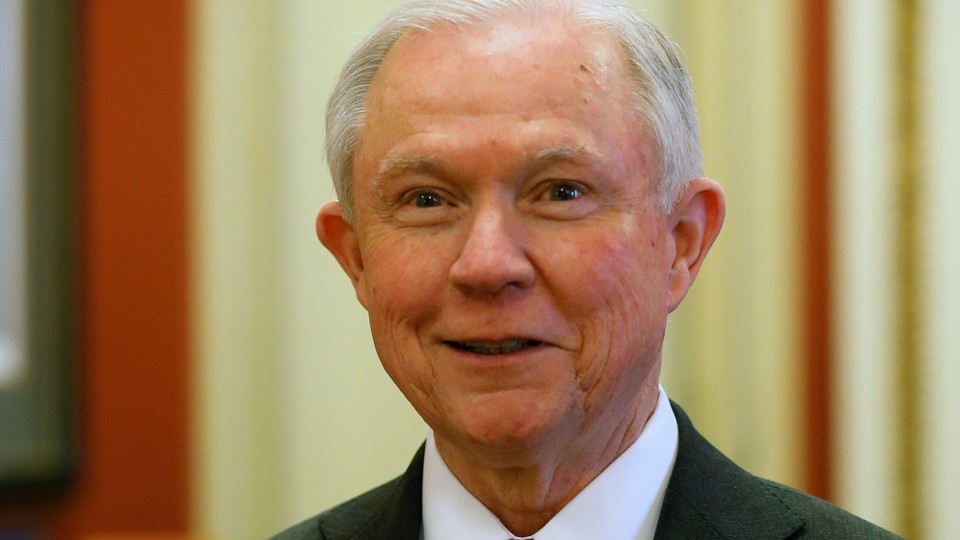

Jeff Sessions's Unqualified Praise for a 1924 Immigration Law

Trump’s pick for attorney general made the remarks during an interview with Breitbart’s Stephen Bannon, now an adviser to the president-elect.

Senator Jeff Sessions, Donald Trump’s nominee to run the Justice Department, once praised a 1924 immigration law whose chief author in the House once declared was intended to end “indiscriminate acceptance of all races.”

Sessions has long been a proponent of immigration restriction, and was one of the first to back Trump’s call on a ban on Muslims entering the United States during the primary.

During an October 2015 radio interview with Stephen Bannon of Breitbart, now a top adviser to the president-elect, Sessions praised the 1924 law saying that:

In seven years we'll have the highest percentage of Americans, non-native born, since the founding of the Republic. Some people think we've always had these numbers, and it's not so, it's very unusual, it's a radical change. When the numbers reached about this high in 1924, the president and congress changed the policy, and it slowed down immigration significantly, we then assimilated through the 1965 and created really the solid middle class of America, with assimilated immigrants, and it was good for America. We passed a law that went far beyond what anybody realized in 1965, and we're on a path to surge far past what the situation was in 1924.

Sessions comments were first flagged by the liberal blog Right Wing Watch.

The 1924 immigration law, known as the Johnson-Reed Act, drastically limited immigration and made permanent restrictions designed to keep out Southern and Eastern Europeans, particularly Italians and Jews, Africans, and Middle Easterners, barring Asian immigration entirely.

Asked about the interview, Sessions’s spokesperson Sarah Isgur Flores wrote in an email, “As Attorney General, Sessions will prioritize curtailing the threats that rising crime and addiction rates pose to the health and safety of our country and that includes enforcing our existing immigration laws.”

Representative Albert Johnson, a Washington Republican described by the historian Edwin Black as a “fanatic raceologist and eugenicist,” used his stewardship of the immigration committee to ensure that racist pseudoscience provided an “empirical” basis for immigration restriction. Immigration historian Roger Daniels put it even more bluntly, writing in Guarding the Golden Door that Johnson’s “racial theories” would “in slightly different form” become “the official ideology of Nazi Germany.”

When the law passed, its primary Senate author, Rhode Island Senator David A. Reed, expressed relief in The New York Times, writing that “the racial composition of America at the time is thus made permanent.”

Sessions’s praise for the 1924 law highlights the difficulty of making the case for immigration restriction, which often relies on popular antagonism toward particular immigrant groups rather than the benefits of restriction per se. The centerpieces of Donald Trump’s immigration policies have been a wall on the U.S.-Mexican border and a ban on Muslims entering the United States.

“I don’t know any historian who would tell you the 1920s law wasn’t a racist law. That was what it was all about. They didn’t try to hide that,” said David Reimers, a professor of history at New York University. The national origin restrictions in the 1924 law were not fully lifted until the passage of the 1965 Nationality and Immigration Act.

Sessions is correct, however, that the percentage of Americans who are foreign born is near record levels. A 2015 Pew report found that 14 percent of Americans were foreign born in 2015, close to the record high of about 15 percent in 1890, and similar to the percentage in 1920, when a rash of immigration-restriction laws was passed. Pew estimates that 18 percent of Americans could be foreign born by 2065.

Some historians have backed up the idea that restricting immigration aided assimilation––by making it easier politically to enact liberal social programs. Historians have also pointed to World War II as a crucial factor in enhancing the stature of “white ethnics,” such as Italians and Jews, once looked upon as inferior to northern Europeans.

“Among the other ironies of that history is that immigration restriction in the twentieth century—along with World War II—was probably a major contributor to the assimilation, and what some historians call ‘the whitening,’ of the millions of southern and eastern European immigrants who had once been widely regarded as a serious danger to the vigorous Nordic ‘germ-plasm’ that had made the country great,” wrote Peter Shrag in Not Fit For Our Society. “Low levels of immigration probably also made it easier to enact the great New Deal and Great Society social programs of the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, just as the existence of those programs today—welfare, health, state and federal support for higher education—probably reinforces pressure to restrict immigration and drive out illegal aliens now.”

Mae Ngai, a history professor at Columbia University, said that “restriction was a factor” in immigrant assimilation through the 1960s but that “others were in my opinion more important,” pointing to “[an] expanding economy, declining income inequality, and the strength of the welfare state.”

Historians’ evaluations of the law have rarely been as effusive or unqualified as Sessions’s, however, even when acknowledging merits to immigration restriction.

“It is easy to see that, in a frontierless democracy, some kind of restriction of immigration was not only inevitable but desirable,” wrote Daniels. “The real tragedy is not that the United States restricted immigration, but that it did so in a blatantly racist way that perpetuated old injustices and created new ones, which endured for decades.”