Shodan is a fictional megalomaniac artificial intelligence network from System Shock, a 1994 video game, symbolized by a female face arcing green lightning. It now also symbolizes a potential ticking time bomb for the US national security apparatus, which is awaiting the possibly devastating consequences of their secret cyber war on Iran: an attack on any one of thousands of computer networks that keep the nation humming along.

"Playing military games with powerful viruses is not merely an assault on our civil liberties as internet users," writes Misha Glenny, author of DarkMarket: How Hackers Became the New Mafia. "In the long run, it will prove a threat to all of our security."

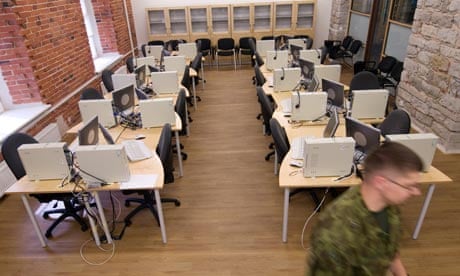

In late 2009, a hacker named John Matherly in San Diego created Shodan, a new search engine, that allows anyone to track down the computer networks that run everything from phones to electric grids. Most, like wifi networks a few years ago, were easily proven to be vulnerable to attack. He named his creation after the computer antagonist of System Shock because of the destructive potential.

Today, it might just prove the adage that those who live in glass houses should not throw stones. The Obama administration has been warning that the Chinese have been hacking into US corporate and government computer networks to steal secrets. What they never mentioned that the White House had signed off on a similar project to wage war on Iran.

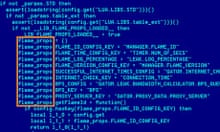

Operation Olympic Games, a secret US intelligence operation that was shepherded into fruition by the Obama administration in collaboration with the Israeli government, is believed to have spawned two sophisticated computer viruses, one named Flame and the other, Stuxnet. The latter caused hundreds of nuclear centrifuges to spin out of control at Iran's uranium enrichment plant in Natanz, while the former attacked the country's oil industry.

That was, apparently, the original intention. But Stuxnet has now escaped the controlled environment of Iran's nuclear apparatus and is roaming the world's cyber networks, awaiting further development by any sophisticated programmers, whether they be in Pakistan or, for that matter, in Brooklyn. Unlike drones, this is a weapon that needs few tools besides a computer and an internet connection.

In doing this, the White House has made a mistake, says experts. "The United States has the most to lose from attacks like these. No other country has so much of its economy linked to the online world," writes Mikko Hypponen, a Finnish cybercrime expert. "By launching Stuxnet, American officials opened Pandora's box. They will most likely end up regretting this decision." Terms like a "digital Pearl Harbor" and "Cybergeddon" are now being tossed around.

The power of the US intelligence apparatus has been much hyped. In Hollywood, the secret services are all powerful, sometimes good and sometimes supremely evil. Reality, however, is very different. For the most part, the intelligence agencies are inept – and by that every token, have often been dangerous.

The Obama administration is currently killing hundreds of people in Pakistan by drone, from half a world away. Drone warfare is neither legal nor particularly accurate, but in unleashing cyber weapons, the US is flying completely blind.

"It is far more difficult to penetrate a network, learn about it, reside on it forever and extract information from it without being detected than it is to go in and stomp around inside the network causing damage," Michael V Hayden, a former CIA director, told the Washington Post. Hayden is hardly a radical, so we should pay heed.

In System Shock, Shodan tells game players:

"My work is only now beginning. Look at you, hacker. A pathetic creature of meat and bone, panting and sweating as you run through my corridors. How can you challenge a perfect, immortal machine?"

What if the machine was mutable by malicious or even unassuming humans? What if a Stuxnet-like virus were to be inserted into the New York power grid discovered via Matherly's Shodan search engine? (I'm no expert but it was designed to do such a thing.) There are proposals to attempt to prevent governments from this indulging in this kind of warfare. Russia and China have formally proposed negotiations to start a global treaty, proposing an arms control-style agreement, which the west opposes.

The west prefers ideas mooted by the UK of a seven "rules of the road" agreement: access for all to the internet, tolerance and respect for diversity of ideas, innovation and the free flow of information, competitive online environment, individual rights of privacy and intellectual property, respect for international law, and collective action against cybercrime. All very well, but we are already into a cyber-arms race. It is time to jettison the idea that this is just about piracy and restart cold war-style arms reduction treaty negotiations – before it is too late.