Undergraduates ride the SURF to an invaluable summer research experience

A junior majoring in neuroscience at USC Dornsife, Daniel Hojoon Kim is determined to become either a neurologist or a neurosurgeon. This summer, he took another important step on his path to realizing that cherished goal when he joined the laboratory of Dion Dickman, assistant professor of biological sciences.

Dickman’s lab researches synapses — the points of communication between two different cells, usually neurons, in the brain.

“We study how synapses develop and function in general, and, in particular, the remarkable plasticity of synapses, which allows them to change in structure and function,” Dickman said.

Synapses are the fundamental units of nervous system function. So any defects in synaptic structure or function, or in their plasticity and ability to change, likely contributes to a variety of neurological and neuropsychiatric diseases, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder.

Dickman’s research may, in the long run, have therapeutic potential for treatment of such diseases.

Dion Dickman, assistant professor of biological sciences. Photo by Peter Zhaoyu Zhou.

Kim joined Dickman’s lab because of his interest in discovering how the nervous system functions and stabilizes itself, perhaps adapting to, and preventing, neurodegenerative diseases. He was able to spend the summer working with Dickman and his team, amassing experience he describes as “invaluable” thanks to funding from the Summer Undergraduate Research Fund (SURF).

“It’s this hands-on reinforcing that I love in the field of research,” Kim said. “You’re not just in class learning about an experiment; you’re actually doing it yourself, reviewing the results, thinking critically about why or how they occurred and how to resolve any issues or discrepancies.”

Fruit flies and jellyfish — a winning combination for science

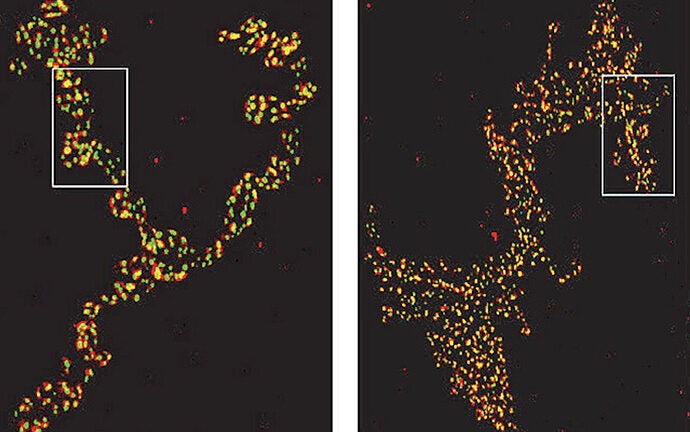

To conduct his research on synapses, Dickman uses the recently developed MiMIC (Minos Mediated Integration Cassette) Library. Created by Hugo Bellen at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, the library holds maintains about a thousand Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly)genes, each tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) at its genomic location. GFP is a gene taken from jellyfish that expresses a protein that glows bright green when placed under blue light.

“The genetics of a fly are very similar to that of a human,” Dickman said. “So studying Drosophila is a great way for young scientists to do real laboratory research and learn how genetics actually works.”

Dickman’s team orders flies from the MiMIC Library with certain GFP-tagged genes that it knows — or suspects — function at synapses.

“First we look at whether we can see green fluorescence at synapses that would indicate that the gene we are interested in actually is expressed and localized to the synaptic structures that we’re interested in,” Dickman said. “If it is, we try then to manipulate those genes and proteins in ways that help us understand their functions at synapses.”

Real-world applications

Dickman’s lab is renowned for its work on a process called homeostatic synaptic plasticity, an adaptive process that keeps the brain functioning at stable levels despite the perturbations that may impair synapses during development, aging, and disease. For example, uncontrolled synaptic activity can lead to the kind of seizures seen in epilepsy. Dickman and his team study the mechanisms that maintain stable synaptic function by trying to identify genes, that when mutated, lead to homeostatic dysfunction at synapse.

Daniel Kim, a junior majoring in neuroscience, is one of the undergraduate researchers in the Dickman Lab to benefit from USC Dornsife’s SURF. Photo courtesy of Daniel Kim.

“The human version of one such gene that we identified in flies is implicated in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,” Dickman said. “So one contributing factor to psychiatric diseases like schizophrenia in humans may plausibly be related to defective homeostatic plasticity. We are therefore keenly interested in identifying genes that function at synapses to control and stabilize their activity.

“Many drugs that we know and that are being developed can target this ability of synapses to adjust their strength and, perhaps, compensate for defective homeostatic control of their activity,” Dickman said.

“We hope that what will emerge from this field will be a better understanding of these diseases and, ideally, better therapeutic ways of intervening to treat and prevent them from happening.”

Learning by doing

In addition to expanding his knowledge of neuroscience and genetics, Kim, who is also pursuing a minor in information technology from USC Viterbi School of Engineering, said the research experience has fostered his ability to work both independently and with academics in a professional setting.

“The laboratory environment really encourages initiative,” he said. “Undergraduates are expected to learn from the senior students quickly, engage intellectually and critically, and contribute to the optimization of the project. I’ve become much more confident and comfortable in both my knowledge of the nervous system and my interaction with others, especially academics.”

A chance to get published

Dickman’s undergraduate research assistants usually have an opportunity to contribute authorship to an academic research paper, which can help them as they apply for graduate or medical school.

“My students work hard, usually 30 to 40 hours a week throughout the summer,” Dickman said. “They also contribute throughout the academic year and typically come on for a second, and sometimes third, summer during their college career. Contributing authorship to a high impact publication while still an undergraduate is a testament to their dedication, work ethic and sustainment of interest in the lab.”

SURF makes it all possible

Dickman describes the undergraduates as “a key asset” in getting important new projects up and running.

“SURF funding is crucial in getting the support needed for the undergraduates to spend the summer working in my lab to get these projects going from scratch,” Dickman said. “Really, none of this would be possible without this generous commitment from USC to undergraduate research through SURF funding. I’m deeply grateful for that.”