It was a salutary lesson for the Royal Society and made clear that the formidable intelligence of its scientific membership was no guarantee of sound business judgement.

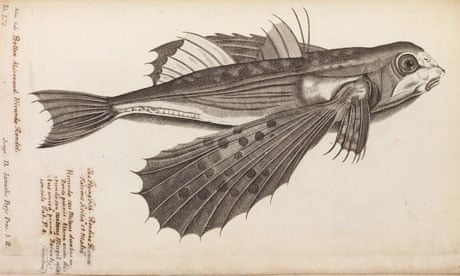

The debacle played out in the 17th century when the country's most prestigious scientific organisation ploughed its money into the lavishly illustrated Historia Piscium, or History of Fishes, by John Ray and Francis Willughby.

Though groundbreaking in 1686, the book flopped and nearly broke the bank, forcing the Royal Society to withdraw from its promise to finance the publication of Newton's Principia, one of the most important works in the history of science.

Today, digital images from Historia Piscium, including a stunning engraving of a flying fish, are made available with more than a thousand others in a new online picture archive launched by the Royal Society.

The images span the society's 350-year history and include highlights from Robert Hooke's 17th century engravings of objects under the microscope; a committee member's doodle of Thomas Huxley from 1882; and the first sighting of a kangaroo, or perhaps a wallaby, by James Cook and the sailors aboard the Endeavour expedition in 1770. Notes accompanying the latter picture state: "it was of a light mouse colour, and in size and shape very much resembling a greyhound."

Among Hooke's illustrations are ink drawings of snowflakes, furrows in ice flakes, and patterns formed on the surface of frozen urine.

Staff will continually add to the archive, so that a growing selection of the society's images becomes available online.

Though Ray and Willughby's masterpiece delayed the publication of Newton's Principia, it was saved from obscurity by Edmund Halley, then Clerk at the Royal Society, who raised the funds to publish the work, providing much of the money from his own pocket. The Principia was eventually published in 1687.

After publishing the work, the Royal Society told Halley it could no longer afford his salary and offered to pay him in unsold copies of the Historia Piscium instead.

"While it may seem surprising to some people that the early fellows of the Royal Society nearly passed up the opportunity to publish Newton's Principia, we mustn't forget that Halley, Newton, Ray and Willughby were all working in the very earliest days of the scientific revolution," said Jonathan Ashmore, chair of the society's library committee.

Ashmore added that he hoped people using the picture archive would appreciate why early fellows of the society were so impressed by Willughby's illustrations.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion