Viruses used to power tiny device

- Published

Scientists in the US have developed a way to generate electricity using viruses.

The researchers built a generator with a postage stamp-sized electrode and based on a small film of specially engineered viruses.

When a finger tapped the electrode, the viruses converted the mechanical energy into electricity.

The research by a team in California has been published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology .

Materials that can convert mechanical energy into electricity are known as "piezoelectric".

"More research is needed, but our work is a promising first step toward the development of personal power generators, actuators for use in nano-devices, and other devices based on viral electronics," said Dr Seung-Wuk Lee at the University of California, Berkeley.

The virus used in the research was an M13 bacteriophage, which attacks bacteria but is benign to humans. The Berkeley team used genetic engineering techniques to add four negatively charged molecules to one end of the corkscrew-shaped proteins that coat the virus.

These additional molecules increased the charge difference between the proteins' positive and negative ends, boosting the voltage of the virus.

Another advantage of using viruses for such tasks is that they arrange themselves into an orderly film that enables the generator to work. This attribute, known as "self-assembly" is much sought after in the field of nanotechnology.

The scientists enhanced the system by stacking films composed of single layers of the virus on top of each other. They found that a stack about 20 layers thick exhibited the strongest piezoelectric effect.

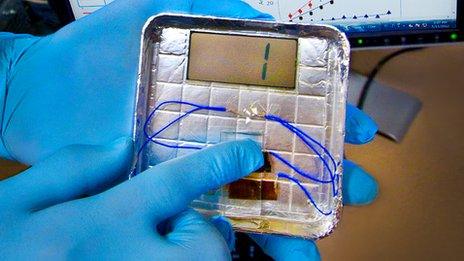

For the demonstration, they took a multilayered film of viruses measuring 1 sq cm and sandwiched it between two gold-plated electrodes. These were connected by wires to a liquid-crystal display.

When pressure was applied to the generator, it was able to produce up to a quarter of the voltage of a common battery. This was enough current to flash the number "1" on the display.

This isn't much, but Dr Lee said he was hopeful of improving on the "proof-of-principle" device.

The researchers claim their advance could help lead to tiny devices that harvest electrical energy from the vibrations of everyday tasks such as shutting a door or climbing stairs.

- Published13 November 2003