Wrongosaurus

‘Dinosaurs’ at the Crystal Palace

By 1854 dinosaurs were, in one sense, old news. Amateur naturalists had been finding inexplicably large bones around the world for centuries, imagining them as the skeletons of everything from biblical giants to legendary dragons.

But as the 19th century wore on, bringing with it a growing acceptance of the concept of extinction, scientists began to conjecture that these fossils might be the remains of long-lost creatures of which we’d previously been wholly unaware. After French naturalist Georges Cuvier’s 1806 drawing of a mastodon skeleton, followed by English paleontologist Richard Owen’s coining of the term “dinosaur” in 1841, the idea of these giant prehistoric monsters was reasonably well established with the general public.

As any visitor to a contemporary natural history museum knows, there’s a world of difference between grasping a concept and standing in its fully embodied, fleshed-out, giant presence. And that’s what the impresarios behind Crystal Palace Park on Sydenham Hill in South London were counting on when, to accompany their relocation of the famed Crystal Palace of the Great Exhibition of 1851, they commissioned sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to create thirty-three life-size dinosaurs for their Dinosaur Court.

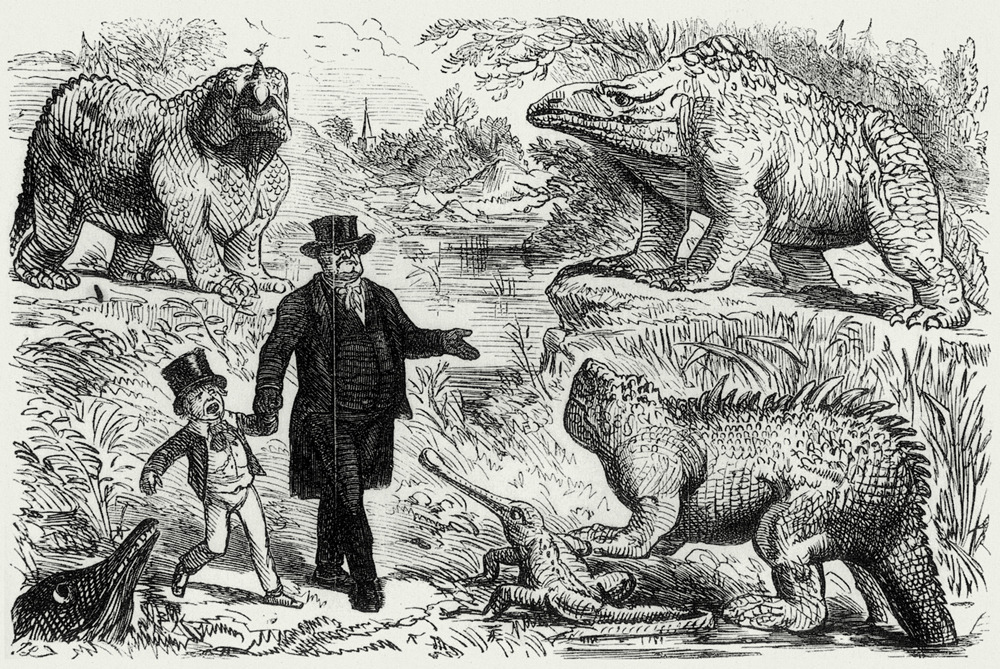

The Extinct Animals’ Model-Room, from the Illustrated London News

In consultation with Richard Owen, Hawkins set to work. The problem, from our vantage, is that Owen simply didn’t have enough fossil evidence from which to extrapolate. For the iguanodon, the largest and most impressive of Hawkins’s sculptures, Owen had little more than a handful of teeth and a few bones, so, he had to make up the rest — which, frankly, was fine by him. As Martin Rudwick explains in Scenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World,

The boldness of this reconstruction was powered by theoretical, even ideological considerations. Owen was determined to turn the fossils into authoritative evidence against the rising tide of evolution in the Lamarckian mode, which he regarded as deeply threatening to both science and society… Only if this relatively ancient reptile had had a more “advanced” anatomy and physiology than living reptiles such as crocodiles— indeed, as advanced as living mammals such as elephants and rhinoceroses — could it refute the intrinsic progressiveness that Lamarckians claimed to see in the history of life.

In order to refute the nascent stirrings of evolutionary theory, Owens pressed Hawkins to transform the iguanodon from the huge, low-to-the-ground lizard that scientists had guessed at since its discovery nearly twenty years earlier into a majestic quadruped that walked rather than slithered, built like a grotesquely oversized dog or pig.

Ultimately, Hawkins’s iguanodon was so large that its open mold accommodated a New Year’s Eve dinner for Hawkins, Owen, and twenty other scientists in 1853.

Mistakes of that sort abounded in Hawkins’s models, driven in most cases less by ideology than by understandable lack of knowledge. As any contemporary visitor to Dinosaur Court will instantly grasp, these dinosaurs are … off. Awkwardly, humorously so. They look far too much like alterations and extensions of extant creatures than like the dinosaurs we’ve come to know (and emotionally domesticate) in the past century and a half.

At the time, however none of that mattered. Forty thousand people showed up to see Queen Victoria open the new Crystal Palace Park, and the dinosaurs were key to the park’s appeal. Punch, the establishment voice of gentle English satire, featured a cartoon of a young boy being terrified by the monsters, their educational value trumped by their sheer size and menace. Rudwick notes,

The fame of Hawkins’s display, as the first major three-dimensional reconstruction of its kind, spread quickly throughout Europe and North America… [I]ts obvious parallel to the living exhibits at the Zoological Gardens a few miles away in Regent’s Park must surely have brought the spectacular otherness of “the ancient world” vividly to the public imagination.

Hawkins’s subsequent fame led to what could have been a spectacular commission: to create a set of dinosaurs for Central Park. Starting in 1868, he spent three years working in a studio in the park, where he created a number of plaster casts — but the dinosaurs fell victim to the rapacity of Boss Tweed: seeing little profit in the idea, he ordered the project scrapped, the studio broken into, and the models destroyed. According to Steve McCarthy and Mick Gilbert in The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs,

The moulds of the animals were dumped into a pond in Central Park. These were recovered not long afterwards, but being made of soft casting plaster they were ruined. The remains of the models themselves were buried in the park and though numerous construction projects have taken place in Central Park in the intervening years, no trace of the smashed models was ever found.

Instead, all we’re left with is a dazzling what-if.

The Central Park Palaeontological Museum As It Might Have Looked.

Over the course of a century after their heyday, the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs would come close to suffering the fate of their originals: rejected by science, neglected by park officials and the public, they languished in increasing decrepitude until the mid-1990s, when the Borough of Bromley begin investigating the possibility of restoration. Four million pounds of grant money later, the dinosaurs are Grade I listed structures, as protected from depredation and decay as any buildings in Britain. Today, the Crystal Palace itself is long gone, destroyed by fire in 1936, but the dinosaurs survive, ranged about a quiet lagoon, their physiological flaws politely corrected by informative signs that do little to detract from their air of toothy menace.

Notes

talkgentlytome liked this

sligoriverblues liked this

thingstoclick liked this

twice-as-many-stars-as-usual liked this

twice-as-many-stars-as-usual liked this grantimatter liked this

nymoon-blog-blog posted this