The Return of the Novella, the Original #Longread

Longer than a short story but shorter than a novel, the form has been the ugly stepchild of the literary world. But that's starting to change.

Publishers like short stories, and they love novels. But when a writer submits a mid-length work that falls somewhere between two genres, booksellers balk and editors narrow their eyes. This is the domain of the novella, an unfairly neglected literary art form that's been practiced for centuries by celebrated writers—from Charles Dickens to Jane Smiley to Alain Mabanckou—yet faces an ongoing struggle for commercial viability. "For me, the word denotes a lesser genre," literary agent Karolina Sutton told The Guardian in 2011. "If you pitch a book to a bookseller as a novel, you're likely to get more orders than if you call it a novella."

Mid-length works suffer from a koan-like criticism: They're too short and they're also too long. Novellas hog too much space to appear in magazines and literary journals, but they're usually too slight to release as books. If a reader's going to spend 16 bucks, the notion goes, he wants to take home a Franzen-size tome—not a slim volume he can slip in a jacket pocket.

As a result, a broad canyon yawns between the viable long story (10,000 words) and the short novel (60,000 words). This is the 50,000-Word Abyss, and anything that falls within it is generally considered untouchable. Most novellas—when they're published at all—are snuck into short story collections. That, or they're consigned to novella ghettoes: three or four mid-length tales forced to live in close quarters, bound and sold as a curiosity.

This trouble extends even to proven mega-sellers. In his scathing Afterword to Different Seasons (1982), his own ghetto of four novellas, Stephen King characterizes himself as a "maturing" writer who could "publish his laundry list if he wanted to." But his novellas? No takers.

"I couldn't publish these tales because they were too long to be short and too short to be really long," he lamented. King illustrates his point with a geographical metaphor: The short story and novel are like two respected nations sharing a vast, ill-defined, and sordid border region. "At some point, the writer wakes up with alarm and realizes that he's come or is coming to a really terrible place," King intones, "an anarchy-ridden literary banana republic called the 'novella.'" It's a dark place for a writer to be, and most feel they must keep going, or else turn back.

Perhaps even more damning than these publishing mores is the lingering aesthetic criticism that haunts the form: A pervading sense that novellas are still not finished, that some measure of necessary pruning, or ballasting exploration, remains undone. Surely, the inability of some writers to go the distance—or, conversely, to edit—has resulted in a flood of bad slush-pile novellas, which do not help the genre's reputation. But even disciplined professionals rarely get the benefit of the doubt. Most writers feel pressure, internal and external, to scale up or pare down to a "suitable" length.

In other words, revise or rewrite the novella out of existence.

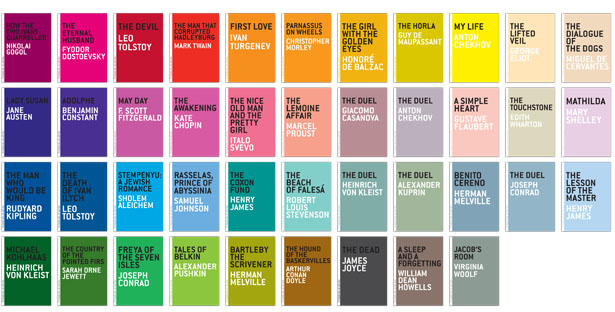

NOW THE BELEAGUERED GENRE, at long last, has found a worthy and consistent champion: Melville House Publishing, whose "Art of the Novella" series is an ongoing celebration of the form. The Brooklyn-based press offers 47—and counting—novellas from writers like Cervantes, Jane Austen, Anton Chekhov, Joseph Conrad, Mark Twain, and Virginia Woolf. Specifically drawing attention to the novella's brevity, diversity, and lineage of distinguished practitioners, the series is the first of its kind.

Each sleek, modernist edition comes suited in a monochrome cover with French flaps. There are no blurb quotes, no graphics or illustrations. Just the author's name, the title, and on the back, a pull quote. At nine dollars each, they're a steal.

Some offerings—this alone is testament to the novella's underdog status—have not previously appeared in English, like Marcel Proust's "The Lemoine Affair." Many are overlooked treasures that have languished in obscurity for years—now revived in new translation, or renewed through updated presentation. With a few exceptions, these stories have never been published as standalone books until now. If you're scouring for a forgotten classic by your favorite canonical writer, or a lost masterpiece by a downtrodden should-have-been, this series is for you.

In its early days, Melville House not only bet against the prevailing wisdom that novellas can't sell—they wagered that novella sales could be the driving engine of their brand and business. "It was greeted as a really numbskull idea by our sales team," co-founder Dennis Loy Johnson told me, in an interview.

Johnson likes to champion the long-shot, the underdog, the also-ran. His company is named for Herman Melville, the Great American Novelist who very nearly never was: Moby-Dick was first in a string of supreme critical failures, and Melville died obscure and penniless. Johnson's website MobyLives.com, which has since been subsumed into MHPbooks.com, was one of the Internet's first book blogs. Its title suggests that hope springs eternal for literary culture. "The whale survived, unlike his detractors, who had harpoons," Johnson wrote on the "About" page. "Similarly, the literary arts will survive, are surviving, these confusing times." This belief informs not only the novella series, but another Melville House project, The Neversink Library (die-hard Melville fans will note another allusion here)—a collection of lost, forgotten, and "foolishly ignored" books from around the world.

In this context, it's not surprising that the novella—impractical, unpublishable—is dear to Johnson. He traces his long, tortured love affair with the form to his days as a graduate student in the Iowa Writers' Workshop. "When I was there," he said, "it felt like all of us were writing novellas, then putting them in the drawer because it was hopeless to place them anywhere." He was daunted by the genre's limited viability—and yet the idealistic prospect of novella-writing pleased him. "It always struck me very romantically," he said. "A pure writerly exercise that was only for the love of writing. We had no expectations our novellas would ever circulate."

I asked him who his novella-writing colleagues were, hoping to hear some now-bold-faced names among them, but he was loath to tell me. "Most of them disappeared," Johnson said. "Probably because they were writing novellas."

JOHNSON HAD A BRIEF PRAYER of giving the form its due. Teaching a novella course at a college, he pieced together an anthology based on his syllabus. "It was a survey stretching from late 19th-century stuff like Chekhov to modern-day examples, such as Tobias Wolff," he said. The Paris Review, at the time, was trying to launch a book publishing line, and acquired the anthology. But the new press folded, like so many of them do, and Johnson's anthology, which was to be called Big Fiction, never saw the light of day.

MORE ON BOOKS

"The Art of the Novella" dates from 2002, when Johnson's own fledgling press—founded with his wife, Valerie Merians, in 2001—was still running on credit cards. "At that point, Melville House was a company that Valerie and I were running off our kitchen table from a 3rd-floor walkup in Hoboken," Johnson told me. Their first book, Poetry After 9/11, had been a surprise hit, and the callow publishers were looking for their next big thing.

"When we started the company I immediately wanted to do a novella line," Johnson said. "I always loved the form and felt that I should champion it. I felt it was neglected. Not only because I had written them and put them away: It just seemed like nobody knew that most of the great writers of history have written novellas."

Their decision to launch a line of classic novellas generated fierce opposition from advisers, and received outright disdain from colleagues in publishing. Johnson remembers a famous publisher, whom he wouldn't name, vowing he would "eat his hat" if they could sell Joyce's "The Dead" as a standalone volume. Thin-lipped sales reps promised that "The Art of the Novella," if greenlighted, would amount to a quixotic and very public form of suicide.

"No one had done it before," Johnson told me. "It was a new idea, and new ideas always meet resistance. The publishing industry, like anything else, is uncomfortable with change. If somebody hasn't done it before, the thinking goes, there must be a reason for it."

Industry consultants especially decried the simple—Johnson would say elegant—single-color editions. He remembers a sales rep angrily accusing him of "wasting the real estate of the cover."

Still, Melville House released their first five novellas, in print runs of 3,000, in 2004. Henry James's "The Lesson of the Master," Anton Chekhov's "My Life," Leo Tolstoy's "The Devil," and a forgotten Edith Wharton gem called "The Touchstone" were the first four. The fifth book was the Herman Melville classic "Bartleby, the Scrivener," available on its own for the first time.

It was large and risky investment, and prognosis, in some corners, was grim. But the strangest thing happened. The novellas began to sell. And sell.

Inadvertently, Johnson said, Melville House "had come up with a way of having a classics line that featured very famous names but lesser-known works in most cases." The series quickly became profitable. Because all the works were public domain, there weren't authors to pay—only translators, and not in all cases. They saved money on the simple design, which turned out to be a boon ("people really responded to not only what the books were, but the look of them," Johnson said. "People liked the look enough to show them off.") The end result was an eye-catching series of "new" and overlooked books by beloved authors, priced reasonably. Customers snapped them up.

"We were lucky in that it worked pretty well pretty quickly," Johnson said. Many of the first books, and the ones that followed, are in multiple printings—even James Joyce's "The Dead." So what about the editor who said it wouldn't sell?

"I have a hat here on my desk, waiting for him," Johnson said.

DESPITE THE SUCCESS of the series, contemporary novella writers still face an uphill battle. Encouraged by the success of their classics line, Melville House launched a sister series called "The Contemporary Art of the Novella," in 2006. Showcasing mid-length works from living authors, this collection of 15 books demonstrates the form's current diversity and vibrancy with works from well-known practitioners like Steve Stern and Lore Segal and young guns like Tao Lin.

Johnson admits that the contemporary series has been a harder sell. The market for new novellas is not large, and it's difficult for living authors to compete with the canonical writers in the classic series. Also, because Melville House must pay its contemporary authors—unlike the classics line authors, whose work is now public domain—the books are twice as expensive to produce. As of now, the old masters are subsidizing the upstarts.

The future of the contemporary novella may lie with a Melville House initiative called HybridBooks. These editions pair each short book with a generous collection of digital supplements, called Illuminations, available through a QR code on the final page. Take "Bartleby," for instance: Illuminations include correspondence related to the story, excerpts from the philosophy that Melville cites, maps of early Wall Street, illustrations of 1850s New York, a contemporaneous ad for a scrivener, and so on—almost 300 pages of supplemental material.

When people fall in love with a book, Johnson told me, they don't want the experience to stop—readers will drift from a story's final page to Wikipedia, to further reading about the character, themes, and world. Melville House wants extend the novella experience through a wealth of high-quality, curated materials; though the series only includes six classic books now, it will continue to grow—eventually including its contemporary counterparts.

MOVING FORWARD, does the besieged novella stand a chance? (Or, as Herman Melville might have put it, "Does the novella diminish? Will it perish?")

One good sign is that the Melville House series has spawned some imitators--most notably, Penguin UK's "Mini Modern Classics" series. These are clearly inspired by—if not a total ripoff of—the Melville House editions. The series' cover layout, streamlined design, and single-color covers are an obvious nod to its antecedent. Surely, interest in mid-length stories from a major publisher is a sign of good things for the form.

I think novellas have intimidated publishers, who cannot easily parse the form. Novellas range so widely in length, from several dozen to over 200 pages, that it's impossible to characterize them as a group. There really is no precise formal definition for what even constitutes a novella, nor will there be—each narrative relies on its own structural logic to determine its length. Writers love this freedom, but for publishers the novella's protean borders are a risk and a headache.

A shame, because it is this very variability that ultimately makes the novella such a dynamic and worthwhile form. Without unnecessary bloat or stricture, novellas are amenable, as Henry James said, to the "idea happily developed" to its own "ideal" length. The novella according to Cather, according to Roth, according to Fallada, will always read differently—but this inconstancy keeps the form from growing stagnant. Shouldn't this formal precision, and capacity for reinvention, count for more than our arbitrary expectation of what a book should "look" like?

For those in need of a definition, then, here's what I would venture. A hybrid form needs two definitions, so I'll mate two. Poe argued that the best literary works—and judging from his own output, he meant the short story—should be readable in "one sitting." The poet Randall Jarrell defined the novel this way: "a prose narrative of some length that has something wrong with it."

Let's define the novella, this way, then: a narrative of middle length with nothing wrong with it, an ideal iteration of its own terms, that can devoured within a single day of reading. I think I'm not alone when I say this is the kind of reading I like best. On a summer Sunday, sometime. We fall under the book's spell in the morning. A friend knocks, the phone rings, the mail clunks through the mail slot. There won't be any stopping until there's nothing left to read. The tempo builds until the pages turn with feverish speed, the sun burns hot and starts to dim. Finally, we're released sometime before dinner. The spell lingers on all through the evening until, at night, we dream.