Abstract

Introduction

The use of social media is rapidly changing how educational content is delivered and knowledge is translated for physicians and trainees. This scoping review aims to aggregate and report trends on how health professions educators harness the power of social media to engage physicians for the purposes of knowledge translation and education.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted by searching four databases (PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and ERIC) for publications emerging between 1990 to March 2018. Articles about social media usage for teaching physicians or their trainees for the purposes of knowledge translation or education were included. Relevant themes and trends were extracted and mapped for visualization and reporting, primarily using the Cook, Bordage, and Schmidt framework for types of educational studies (Description, Justification, and Clarification).

Results

There has been a steady increase in knowledge translation and education-related social media literature amongst physicians and their trainees since 1996. Prominent platforms include Twitter (n = 157), blogs (n = 104), Facebook (n = 103), and podcasts (n = 72). Dominant types of scholarship tended to be descriptive studies and innovation reports. Themes related to practice improvement, descriptions of the types of technology, and evidence-based practice were prominently featured.

Conclusions

Social media is ubiquitously used for knowledge translation and education targeting physicians and physician trainees. Some best practices have emerged despite the transient nature of various social media platforms. Researchers and educators may engage with physicians and their trainees using these platforms to increase uptake of new knowledge and affect change in the clinical environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

This paper comprehensively maps the evolving landscape of how social media is changing the way medical educators use social media to translate knowledge or educate end-user physicians and their trainees. The authors highlight gaps and opportunities for further scholarship and research, while succinctly describing the current state of the literature.

Introduction

For over a decade, social media has become an increasingly powerful tool harnessed by physicians to disseminate knowledge to one another, their learners, patients and the public [1,2,3]. Defined broadly, social media includes technology-mediated platforms that facilitate individual users to create and distribute content (both user-generated and user-curated) to virtual communities of practice [4, 5]. These platforms can range from collaborative authorship platforms such as wikis (e.g., Wikipedia) to single-author dialogue platforms such as micro-blogging (e.g., Twitter) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Many potential uses of social media have emerged, and increasingly journals, scientists, and researchers are using it for reaching their end users and engaging in education and knowledge translation. Knowledge translation is defined as the communication between scientists, healthcare professionals, educators, and journals to convey information [2]. As personal use of social media has grown, so has its use for purposes of knowledge translation. Initially, this included mostly dissemination via blogs, wikis, and podcasts, but more recently has evolved to include other media, such as microblogging (e.g., Twitter), social networks (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn), and video-based outlets (e.g., YouTube). Increasingly, academic journals are leveraging social media to encourage readers to engage with their materials [14] and are experimenting with using online social media conversations [15, 16], infographics [17, 18] and podcasts [17, 19, 20] to increase readers’ awareness of new publications. In many ways, knowledge translation is a scientist-based description of a phenomenon that overlaps with the individual end-user’s education, especially when they intersect within social media platforms. As such, for the purpose of our scoping review we have coalesced the concepts of education and knowledge translation, since we felt that we would be unlikely to make true distinctions in our synthesis of the literature.

While there have been some reviews about the use of social media for education [21,22,23,24], none have sought to fully encompass the breadth of how these technologies have affected the full spectrum of education, including the continuing professional development of practising physicians. Interestingly, in both postgraduate and continuing medical education, the lines between knowledge translation and education often blur since new knowledge that is being disseminated or translated by scientists is often being consumed by trainees and practising physicians as part of their continuing lifelong learning.

The purpose of this scoping review is to describe the breadth of social media-based technologies used for knowledge translation, as well as dissemination strategies used by scientists, educators, and journals to educate clinical colleagues. We aim to map the landscape of knowledge translation and education via social media in academic medicine. Through this scoping review, we hope that by examining and synthesizing the work that has come so far, we can identify trends and best practices for engaging in knowledge translation and education in today’s social media-laden world.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, which features six steps as outlined below [25]. A scoping review methodology was selected to enable us to characterize the current literature and identify gaps. Our initial database extraction occurred on 27 March 2018; the remaining phases of our study were conducted over the following year.

Step 1: Identifying the research question

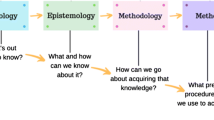

In this review, we focused on three key questions: 1) What are the most frequently reported knowledge translation and education strategies using social media? 2) How are these strategies most frequently reported? 3) Has the effectiveness of these social media strategies been reported, and if so, what were the primary outcomes?

Our questions were generated through an iterative process of discussion within our research team and shaped by consultation of the literature. The research team also drew upon its extensive experience with various social media platforms and conducting research in this domain.

Step 2: Identifying relevant studies

Based on our research questions, LAM, a health professions education researcher and information scientist, designed a PubMed search using Boolean operators to combine medical subject heading terms and keywords. Search terms included, but were not limited to: social media, Facebook, Twitter, Web 2.0, medical education, physicians, medical students (See Supplement 1 of the online Electronic Supplementary Material for the complete search strategies).

An independent medical librarian peer reviewed the PubMed search strategy to ensure its comprehensiveness. After discussion with LAM, the medical librarian translated the PubMed search for optimal use in Scopus, Embase, and ERIC, and ran the searches in all databases on 27 March 2018. No limits related to language or date range were applied. Upon retrieval, results from all databases were deduplicated and exported for management into Excel.

Step 3: Study selection

The author team participated in multiple conference calls to determine inclusion criteria. During these calls, we iteratively reviewed articles discussing relevance to the research questions until group consensus was reached. Ultimately, we decided to focus on articles that included social media as a communication tool targeted towards physicians and/or medical trainees. We excluded publications reporting on physician-patient communications or those purely focused on online professionalism, personal reflection without a practice improvement focus, and physician/trainee identity formation. Lastly, we excluded publications simply describing social media as a broadcasting tool.

To facilitate study selection, we restricted database searches to journal articles and conference proceedings, including white papers, indexed in our selected databases. We excluded scholarly blogs or websites because they are not uniformly indexed across the various databases. Citations, selected for full-text review, not in English were translated by the lead author (TC) using Google Translate.

Step 4: Charting the data

In alignment with our research question and informed by the Best Evidence in Medical Education data extraction tool [26], we iteratively designed a data extraction sheet in Excel. We based portions of the extraction tool on the Cook, Bordage, and Schmidt framework for types of scholarship (description, justification, and clarification) [27]. Additionally, we classified outcomes measured in empirical studies according to Kirkpatrick’s evaluation framework [28, 29]. All authors piloted this extraction sheet using a randomly selected sample of 10 articles. Upon finalizing the extraction tool, it was operationalized in Google Forms (Mountainview, CA) for ease of data entry. (For the extraction tool see Supplemental Appendix 1).

Step 5: Collating, summarizing and reporting the data

The list of studies for extraction was divided equally amongst the authors. Each author was responsible for including or excluding the study as well as extracting relevant information from included studies. Studies that were classified as ‘maybe include’ were reviewed by a second author for a final decision. Studies not in English were also included and underwent the same review process. Google Translate (Mountainview, CA, USA) was used to translate the content and decide accordingly.

Throughout our extraction process, we identified key themes related to the educational use of social media for knowledge translation. Initially, based on our familiarity with the field and literature, we started with a working list of potential key concepts that sensitized our approach. However, we also iteratively added to this list throughout data extraction. The themes and the analysis of our extraction were reviewed by our consulting experts to ensure the rigour of the findings (see below).

Step 6: Consultation

After our data extraction, we consulted three researchers who have published at least five publications on social media use in relation to knowledge translation and education and act as active practitioners (e.g., heading an online education blog, serving as social media editor for a major medical journal). These consulting researchers were known to the lead investigator (TMC) and had co-authored multiple papers in the area of social media-based knowledge translation and education.

Each consultation consisted of one-on-one interviews, with TMC walking them through our key findings (e.g., she presented our collated and summarized data regarding the literature that we found). The themes, tables, and findings were discussed with these individuals, and their feedback on our findings was sought. Specifically, we asked each individual if our findings were consistent with their own understanding of the status of the literature and if there were any specific gaps in our analyses. Further analyses suggested by the experts were incorporated into our final manuscript, specifically in the results in one of our tables (specifically indicated in the results section) and discussion sections.

Results

Our search retrieved 9634 potential citations, which based on our criteria were reduced to 628, the full-texts of which were analysed (See Fig. 1 for a flow diagram of the results). We were unable to locate the full-text of 11 publications despite searching 5 separate institutional libraries and emailing corresponding authors three times. These publications were excluded.

Many of the publications (n = 228) were not geographically anchored (e.g., they did not refer to a specific region of the world). For the remainder, the majority were in North American (n = 187) or European (n = 88) contexts, although there were publications from many other jurisdictions [Asia (n = 31), Australia/New Zealand (n = 20), Middle East (n = 11), Africa (n = 5), South America (n = 4)].

Prevalence over time

Over the past decade, publications featuring social media for knowledge translation and education of physicians and medical trainees have increased (See Fig. 2).

Number of publications on social media knowledge translation and education for physicians and medical trainees. NB The 2018 data is extrapolated from projected data since our search included only the first 3 months of 2018. To generate the year-end projection, the number of papers published in the first 3 months was multipled by four to yield the anticipated total number of papers by year’s end

Specialties of origin

We identified a range of specialties, with surgical specialties most often represented. (See Table 1 for specialties or groups of specialties that were included in more than 10 publications.)

Target audiences

The majority of articles targeted attending (fully qualified and practising) physicians (n = 346) and postgraduate trainees (e.g. residents and fellows, n = 242). Of the articles, 195 described interventions aimed to educate or disseminate new knowledge to medical students in addition to other learners, with 20 of these publications focusing on preclinical basic science, and 11 focusing exclusively on undergraduate medical education. Eighty-three articles addressed our target audiences plus at least one other health professional group (e.g., nurses, dentists). The majority of papers within all of the groups tended to address similar issues (i.e., using social media for learning, uptake and usage), although the articles targeting trainees/students tended to have more content regarding professionalism (many of which were excluded in our final analysis).

Social media strategies used for knowledge translation and education

Prevalence of types of social platforms

A wide range of social media platforms were featured, including Twitter (n = 157), blogs (n = 104), Facebook (n = 103), podcasts (n = 72), video archival platforms (e.g. YouTube, n = 68), and Wikipedia (n = 57) (See Table 2 for a comprehensive platform listing). The majority of articles focused on the technology itself (77.5%, n = 487) (e.g., an article that introduces a medical specialty to Twitter [30, 31]), whereas the remainder focused on the individuals using the technology (22.5%, n = 141), such as the rate at which residents used podcasts or blogs [10, 32].

Strategies described using social media platforms to engage in knowledge translation and education

Reviewed publications described many social media strategies. These strategies focused on ways to push out information or foster engagement. For example, several studies described organized efforts by journals, professional societies, and individuals to push journal articles to their audiences, such as creating a podcast to showcase a recent article. Other common strategies focused on fostering interaction between individuals. For example, multiple residencies reported using social media to facilitate engagement around journal articles using a virtual journal club format. In several cases, strategies contained both efforts to push information and foster engagement. Table 3 features examples of identified strategies. This table specifically arose because of our expert consultation process.

Types of social media scholarship in knowledge translation and education

The bulk of included publications (n = 242) were descriptive studies of physicians’ social media usage for the purposes of knowledge translation and education. Another prominent scholarship type (n = 192) was conceptual or narrative reviews describing the application of social media for connecting physicians and their trainees. Innovation reports were the next most prevalent type of scholarship (n = 122). A minority of studies included elements of clarifying between types/formats of social media for knowledge translation and education (n = 5), critical appraisal of social media-based content (n = 5), and integrative reviews of social media (n = 3). Table 4 lists types of scholarship in knowledge translation and education.

Empirical studies

The majority of empirical studies (n = 353) applied quantitative methods (79.9%, n = 282). Forty-four studies utilized mixed methods (12.5%, n = 44) and a minority featured qualitative methods (7.5%, n = 27). Five studies critically appraised online content and two reported consensus building using modified Delphi methods.

Methods used in studies about knowledge translation and education for physician audiences were varied. The predominant study design was the quantitative survey (n = 180 studies), which was often mixed with other methods such as free-text survey questions. Usage analytics were also popular (n = 79). Other common study types included applying objective observations or text analysis of substantive written texts (e.g., blog posts or archived narratives), interviews, and micro-text (e.g. Tweet) analysis. Table 5 reports all methods used.

Within empirical studies, multiple themes were discerned via our analysis of these types of articles. We identified the feasibility of social media for practice improvement as the most prevalent theme (n = 330). Multiple publications also described specific elements of a particular technology (n = 327), such as podcasts or e‑learning. Examples of these studies were: a) Lien and colleagues comparing blog posts to podcasts; both groups showed increased knowledge retention, with no preference for one media over the other [33]; b) multiple studies examined the use of mixed media (podcasts, video) for medical students and resident translation of learning, ultimately concluding that learners rated the media tool more highly than traditional learning [34, 35]; c) other studies have examined use of Twitter as a study aid or engagement tool in student courses, but have not shown improved performance [36, 37].

Table 6 features major themes identified and provides a reference to exemplar papers. Some of the rarer themes included: challenges and pitfalls aside from professionalism (n = 5), humanism (including medical humanities and reflective practice, n = 3), costs of the innovation (n = 2), correlation of social media with bibliometrics (n = 2), health policy change and advocacy (n = 2), informatics (n = 1), and mentorship (n = 1).

Outcomes measured in social media for knowledge translation and education studies

Most (134; 70.1%) articles measuring outcomes were at the acceptability level. For example, in one study researchers developed audiovisual podcasts, which were reviewed by medical students to assess their usability [45]. Forty-eight studies (24.7%) measured knowledge acquisition. For example, one research team conducted a prospective, nonblinded, three-arm randomized trial to compare use of Wikipedia, UpToDate, and a digital textbook for knowledge acquisition among pre-clerkship students to assess knowledge acquisition [46]. Six studies (3.1%) measured behavioural change. Finally, four studies (2.0%) measured organizational or patient outcomes. For example, one study compared the use of emergency department communications and peer-to-peer learning via WhatsApp and standard telephone for educating peers during consultations [47].

Diffusion of an innovation through scholarship

There appeared to be a diffusion of innovation that has moved into more scholarly avenues—a diffusion of innovation through scholarship. Akin to Rogers’ framework for diffusions of innovation [48, 49], we found a pattern in our review of the literature. We have assembled our findings into a new conceptual framework, which highlights specifically how educational innovations seem to diffuse through the scholarly system. For instance, we observed the trend of narrative papers commenting about the potential and usage of social media, moving into more descriptive papers about the phenomenon via surveys and demographics-based studies, with patterns of usage and preferences for usage appearing in tandem with the more narrative literature. Soon after, the one-off, single-centre innovation publications emerged—variably describing interventions, reporting new ideas for application, with a mind for others to replicate and reproduce. After the appearance of descriptive publications come the justification articles (which seek to substantiate why a certain innovation is worthy) [27]. Finally, there are the clarification papers (which seek to clarify ‘what works’) [27] and the critical appraisal publications, which seek to set standards and examine the innovation via a more critical lens. Fig. 3 depicts the scholarly sequence that social media for knowledge translation and education seemed to have appeared in our review; the stages were not discrete and often overlapped as the field tended to mature over time.

Discussion

In the past few decades, there has been a veritable boom of scholarly work describing the ways social media can be used for knowledge translation and education; our scoping review maps the trends of these uses of social media. In these next sections, we discuss the social media landscape highlighting trends and possible future research directions.

The landscape of social media for knowledge translation and education has shifted from simple descriptions to more nuanced clarifications around best practices and bringing an element of criticality to its implementation. More recent publications seek to justify and clarify the use of social media for knowledge translation and education tended to aim for higher Kirkpatrick outcomes (e.g., Level 4—measuring organizational changes, Level 3—behavioural changes, Level 2—knowledge change) rather than simply reporting acceptability (Kirkpatrick Level 1) [29]. Likely, it is time for scholars to shift from simply engaging in descriptive or conceptual papers focused on highlighting specific social media platforms towards more justification and clarification work—after all, our search shows that platforms tend to rise and fall (e.g., MySpace is barely mentioned, while the dominance of Twitter or Facebook may someday similarly decline).

The emerging power of online communities

Sixty-one publications addressed online communities. The growth of the Free Open Access Medical education (FOAM, or #FOAMed) movement has fostered the growth of hundreds of English-language blogs and podcasts in two specialties alone (emergency medicine and critical care) [1]. Fuelled by the growing FOAM movement [1, 50], they have started to embrace alternative outlets for knowledge translation and dissemination: for example, exchanging information and ideas about new research, evidence, or guidelines by tweeting and using specialty specific hashtags. Whether to share conference pearls [51,52,53,54], discuss best practices via a podcast [55], or utilization of online platforms for faculty teacher development [44, 56], there is now an unprecedented ability to share information beyond traditional venues (e.g. conferences or publications).

Enabled by networks such as those that have sprung up around FOAM, virtual communities of practice can enable members to more quickly share common knowledge [57, 58]. There are growing numbers of online communities of practice, which not only allow, but encourage educators to increase peer visibility and recognition. They can also be harnessed to amplify messages, allowing for a faster dissemination of work, theoretically leading to increased immediate impact [57]. Because of the growth of virtual communities of practice [4, 5, 59, 60] which facilitate innovative knowledge translation, new educational approaches, and dissemination practices, the best practices for using social media to translate new knowledge to other healthcare professionals is a moving target.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, although we searched several databases, attempting to optimize our search strategies for comprehensiveness, it is possible we inadvertently missed citations. Secondly, we did not assess publication quality or impact. Instead, we aimed to include rather than exclude publications to provide a comprehensive overview to inform future scholarship. We also used Google Translate to translate non-English papers. Had we conducted a more complex textual review, we might have utilized another tool or translation services, which more effectively captures the nuance of language. However, for the purposes of our data extraction (Appendix 1), we only extracted surface features so Google Translate was appropriate for our purpose.

Purposefully, we broadly defined social media to avoid preconceived notions of what is traditionally deemed as ‘social media’ per popular definitions. We aimed to include technology that linked two or more individuals in direct exchanges and engagement, excluding one-way communication methods (pure broadcasting via e‑modules) or more traditional formats of correspondence such as e‑mail and listservs. Additionally, we excluded social media use as it relates to professionalism, which was a popular topic in the literature but did not embody our primary study purpose. Also, as noted in the introduction there is considerable overlap between knowledge transfer and education. This finding was underscored by how these two concepts were intertwined in the included studies; it was impossible to disentangle these two concepts, so we addressed them together. Future researchers might consider focusing on the different ways in which medical education addresses these two concepts in relation to social media. Finally, our review was limited to social media which targeted physicians and trainees, and as such cannot comment on other groups of healthcare providers or scientists.

Next steps: Gaps & opportunities

In our review, we observed prevalent themes and those that have been less explored, but are ripe for future research. We identified that only two publications examined costs related to social media in the context of knowledge transfer and education, which could be considered a major challenge for this field [61, 62]. While most social media platforms are free to use (e.g., there is no charge operating a Twitter account), it remains important to consider time and energy costs associated with these platforms, such that the set-up, monitoring, and maintenance of an individual or group’s presence on a platform can be time consuming. Future researchers should consider studying the return on investment for such efforts in knowledge translation and educational goals.

Looking ahead, researchers might also consider alternative framing for future studies. In many studies, we observed that researchers focused on a particular social media platform. However, some social media platforms (e.g. MySpace) rise and fall rapidly making these studies quickly obsolete. To extend the half-life of such studies, researchers should consider pushing the field towards more generalizable or transferrable concepts, such as identifying particular characteristics or features of platforms that align with educational theories or models.

Conclusions

Our review found that social media platforms are ubiquitously used tools for knowledge translation and education targeting physicians and physician-trainees. Some best practices have emerged despite the transient nature of various social media platforms. Researchers and educators may find these media useful to engage with physicians and trainees to increase uptake of new knowledge and affect change in the clinical environment.

References

Cadogan M, Thoma B, Chan TM, Lin M. Free Open Access Meducation (FOAM): the rise of emergency medicine and critical care blogs and podcasts (2002–2013). Emerg Med J. 2014;31(e1):e76–e7.

Choo EK, Ranney ML, Chan TM, et al. Twitter as a tool for communication and knowledge exchange in academic medicine: a guide for skeptics and novices. Med Teach. 2015;37:411–6.

Chan TM, Stukus D, Leppink J, et al. Social media and the 21st-century scholar: how you can harness social media to amplify your career. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;15:142–8.

Dube L, Bourhis A, Jacob R. Towards a typology of virtual communities of practice. Interdiscip J Inf Knowl Manag. 2006;1:69–93.

Dubé L, Bourhis A, Jacob R. The impact of structuring characteristics on the launching of virtual communities of practice. J Organ Chang Manag. 2005;18:145–66.

McGee JB, Begg M. What medical educators need to know about ‘Web 2.0’. Med Teach. 2008;30:164–9.

McKibbon KA, Lokker C, Keepanasseril A, Colquhoun H, Haynes RB, Wilczynski NL. WhatisKT wiki: a case study of a platform for knowledge translation terms and definitions—descriptive analysis. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):13.

Grajales FJ, Sheps S, Ho K, Novak-Lauscher H, Eysenbach G. Social media: a review and tutorial of applications in medicine and health care. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e13.

Sparks MA, O’Seaghdha CM, Sethi SK, Jhaveri KD. Embracing the Internet as a means of enhancing medical education in nephrology. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:512–8.

Purdy E, Thoma B, Bednarczyk J, Migneault D, Sherbino J. The use of free online educational resources by Canadian emergency medicine residents and program directors. CJEM. 2015;17:101–6.

Archambault PM, Van De Belt TH, Grajales FJ, et al. Wikis and collaborative writing applications in health care: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:10.

Cabrera D, Cooney R. Wikis: using collaborative platforms in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8:99–100.

Boulos MNK, Maramba I, Wheeler S. Wikis, blogs and podcasts: a new generation of web-based tools for virtual collaborative clinical practice and education. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:41.

Lopez M, Chan TM, Thoma B, Arora VM, Trueger NS. The social media editor at medical journals. Acad Med. 2018;94:701–7.

Roberts MJ, Perera M, Lawrentschuk N, Romanic D, Papa N, Bolton D. Globalization of continuing professional development by journal clubs via microblogging: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e103.

Lin M, Joshi N, Hayes BD, Chan TM. Accelerating knowledge translation: reflections from the Online ALiEM-annals global emergency medicine journal club experience. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:469–74.

Thoma B, Murray H, Huang SYM, et al. The impact of social media promotion with infographics and podcasts on research dissemination and readership. CJEM. 2018;20:300–6.

Ibrahim AM, Lillemoe KD, Klingensmith ME, Dimik JB. Visual abstracts to disseminate research on social media: a prospective, case-control crossover study. Ann Surg. 2017;266:e46–e8.

Ahn J, Inboriboon PC, Bond MC. Podcasts: accessing, choosing, creating, and disseminating content. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8:435–6.

Cho D, Cosimini M, Espinoza J. Podcasting in medical education: a review of the literature. Korean J Med Educ. 2017;29:229–39.

Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88:893–901.

Rolls K, Hansen M, Jackson D, Elliott D. How health care professionals use social media to create virtual communities: an integrative review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e166.

Guraya SY. The usage of social networking sites by medical students for educational purposes: a meta—analysis and systematic review. N Am J Med Sci. 2019;8:268–78.

Cartledge P, Miller M, Phillips BOB. The use of social-networking sites in medical education. Med Teach. 2013;35(10):847–57.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Hart IR, et al. Simulation technology for health care professional skills training and assessment. JAMA. 1999;282:861–6.

Cook DA, Bordage G, Schmidt HG. Description, justification and clarification: a framework for classifying the purposes of research in medical education. Med Educ. 2008;42:128–33.

Frye AW, Hemmer PA. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE Guide No. 67. Med Teach. 2012;34:e288–e99.

Yardley S, Dornan T. Kirkpatrick’s levels and education ‘evidence. Med Educ. 2012;46:97–106.

Melvin L, Chan T. Using twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:581–2.

Thoma B, Joshi N, Trueger NS, Chan TM, Lin M. Five strategies to effectively use online resources in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:392–5.

Mallin M, Schlein S, Doctor S, Stroud S, Dawson M, Fix M. A survey of the current utilization of asynchronous education among emergency medicine residents in the United States. Acad Med. 2014;89:598–601.

Lien K, Chin A, Helman A, Chan TM. A randomized comparative trial of the knowledge retention and usage conditions in undergraduate medical students using podcasts and blog posts. Cureus. 2018;10:1–12.

Narula N, Ahmed L, Rudkowski J. An evaluation of the ‘5 Minute Medicine’ video podcast series compared to conventional medical resources for the internal medicine clerkship. Med Teach. 2012;34:e751–e5.

Hempel D, Haunhorst S, Sinnathurai S, et al. Social media to supplement point-of-care ultrasound courses: the ‘sandwich e‑learning’ approach. A randomized trial. Crit Ultrasound J. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-016-0037-9.

Hennessy CM, Kirkpatrick E, Smith CF, Border S. Social media and anatomy education: using twitter to enhance the student learning experience in anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2016;9:505–15.

Webb A, Dugan A, Burchett W, et al. Effect of a novel engagement strategy using twitter on test performance. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16:961–4.

Alam F, et al. E‑learning optimization: The relative and combined effects of mental practice and modeling on enhanced podcast-based learning—a randomized controlled trial. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2016;21:789–802.

Sugawara Y, et al. Medical Institutions and Twitter: A Novel Tool for Public Communication in Japan. JMIR Public Health Surv. 2016;2(1):e19.

Stewart S, Abidi S. Applying social network analysis to understand the knowledge sharing behaviour of practitioners in a clinical online discussion forum. JMIR. 2012;14(6):e170.

Wolbrink T, et al. The top ten websites in critical care medicine education today. J Int Care Med. 2018;34:3–16.

Chretien K, et al. Physicians on twitter. JAMA. 2011;305:566–8.

Joshi N, et al. Social media responses to the annals of emergency medicine residents [57] perspective article on multiple mini-interviews. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:320–5.

Chan TM, et al. Creating, curating, and sharing online faculty development resources: the medical education in cases series experience. Acad Med. 2015;90:785–9.

Shantikumar S. From lecture theatre to portable media: Students’ perceptions of an enhanced podcast for revision. Med Teach. 2009;31:535–8.

Scaffidi MA, Khan R, Wang C, et al. Comparison of the impact of Wikipedia, uptodate, and a digital textbook on short-term knowledge acquisition among medical students: randomized controlled trial of three web-based resources. JMIR Med Educ. 2017;3:e20.

Gulacti U, Lok U, Hatipoglu S, Polat H. An analysis of whatsapp usage for communication between consulting and emergency physicians. J Med Syst. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-016-0483-8.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press; 1995.

Sanson-Fisher RW. Diffusion of innovation theory for clinical change. Med J Aust. 2004;180(6 suppl.):55–6.

Nickson CP, Cadogan MD. Free Open Access Medical education (FOAM) for the emergency physician. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26:76–83.

McKendrick DRA, Cumming GP, Lee AJ. Increased use of Twitter at a medical conference: a report and a review of the educational opportunities. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e176.

Neill A, Cronin JJ, Brannigan D, O’Sullivan R, Cadogan M. The impact of social media on a major international emergency medicine conference. Emerg Med J. 2014;31:401–4.

Pemmaraju N, Thompson MA, Mesa RA, Desai T. Analysis of the use and impact of twitter during American society of clinical oncology annual meetings from 2011 to 2016: focus on advanced metrics and user trends. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:JOP2017021634.

Loeb S, Bayne CE, Frey C, et al. Use of social media in urology: data from the American Urological Association (AUA). BJU Int. 2014;113:993–8.

Mcguire M. Using podcasting and blogging to create and share open educational resources—Usando podcasting e blogs para criar e compartilhar recursos educacionais abertos. Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications. 2010. pp. 1536–44.

Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Sherbino J, et al. The ALiEM faculty incubator. Acad Med. 2018;93:1497–502.

Ting DK, Thoma B, Luckett-Gatopoulos S, et al. CanadiEM: accessing a virtual community of practice to create a Canadian national medical education institution. AEM Educ Train. 2019;3:86–91.

Thoma B, Brazil V, Spurr J, et al. Establishing a virtual community of practice in simulation: the value of social media. Simul Healthc. 2018;13:123–30.

Lave J, Wenger EC. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

Bourhis A, Dubé L, Jacob R. The success of virtual communities of practice: the leadership factor. J Knowl Manag. 2005;3:23–34.

Parthasarathi R, Gomes RM, Palanivelu PR, et al. First virtual live conference in healthcare. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27:722–5.

Grover S, Kelmenson AT, Chalam KV, Edward DP. Webcasts for resident education. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:199–200.e1.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Rhonda Allard, a medical librarian at Uniformed Services University for her assistance in conducting database searches for this study. We would also like to thank Damian Roland, Brent Thoma, and N. Seth Trueger for their expert consultation on this paper.

Funding

Dr. Chan received the PSI Graham Farquharson Knowledge Translation Fellowship, which funded her work on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

T.M. Chan received the PSI Graham Farquharson Knowledge Translation Fellowship, which funded her work on this paper. K. Dzara, S. Paradise, A. Bhalerao and L.A. Maggio declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, T.M., Dzara, K., Dimeo, S.P. et al. Social media in knowledge translation and education for physicians and trainees: a scoping review. Perspect Med Educ 9, 20–30 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-00542-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-00542-7