A couple of weeks ago we published a blogpost asking whether A-Level maths was a requirement for A-Level physics and computer science.

Several readers got in touch to ask the very reasonable question of whether students who entered A-Level maths tended to achieve higher grades than those who didn’t. This is the subject of this article.

Data

I use data for 2019, the last year in which A-Levels were awarded by examination (at the time of writing). I include all students aged 16-18 who entered 2 or more A-Levels that summer. I also include all types of establishment: state-funded schools, independent schools and FE colleges (including sixth form colleges).

Attainment by subject

The chart shows the average point score (APS) [1] in the most popular A-Level subjects (at least 5000 entrants) for both students who entered A-Level maths and those who didn’t.

In all subjects shown, students who enter A-Level maths tend to achieve higher grades than those who don’t.

Of course, this isn’t causal. There’s nothing here to say that making everyone take A-Level maths will lead to improvements in A-Level results in other subjects. Rather, it suggests that those who enter A-Level maths tend to have higher levels of prior attainment to begin with.

The table also shows that the difference in attainment between those who enter A-Level maths and those who don’t is greatest in physics and computer science.

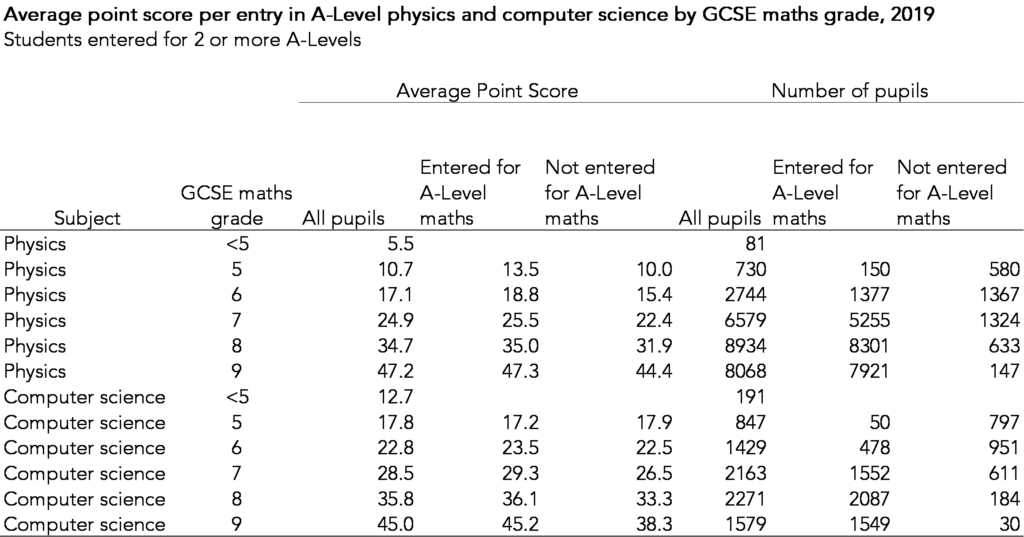

Most of this gap in attainment can be attributed to existing differences in maths attainment prior to starting A-Levels. In the table below I show how attainment in physics and computer science varies by GCSE maths grade for the two groups of students. Here I restrict the analysis just to those students who took GCSE maths in 2017.

Adjusting for GCSE maths reduces the gap in A-Level physics between those who entered A-Level maths and those who didn’t from 15 to 3 points. Figures for computer science were 12 points and 3 points respectively.

On average, students with grade 7 in GCSE maths go on to achieve 25.5 points on average (between grade C and grade D) in A-Level physics. In computer science this figure was 29.3 points (almost exactly grade C).

Which begs the question whether physics is graded too severely.

Is physics graded too severely?

Back in 2015, I wrote this article asking whether A-Level physics was graded too severely. In short, I thought it was. Nothing seems to have changed.

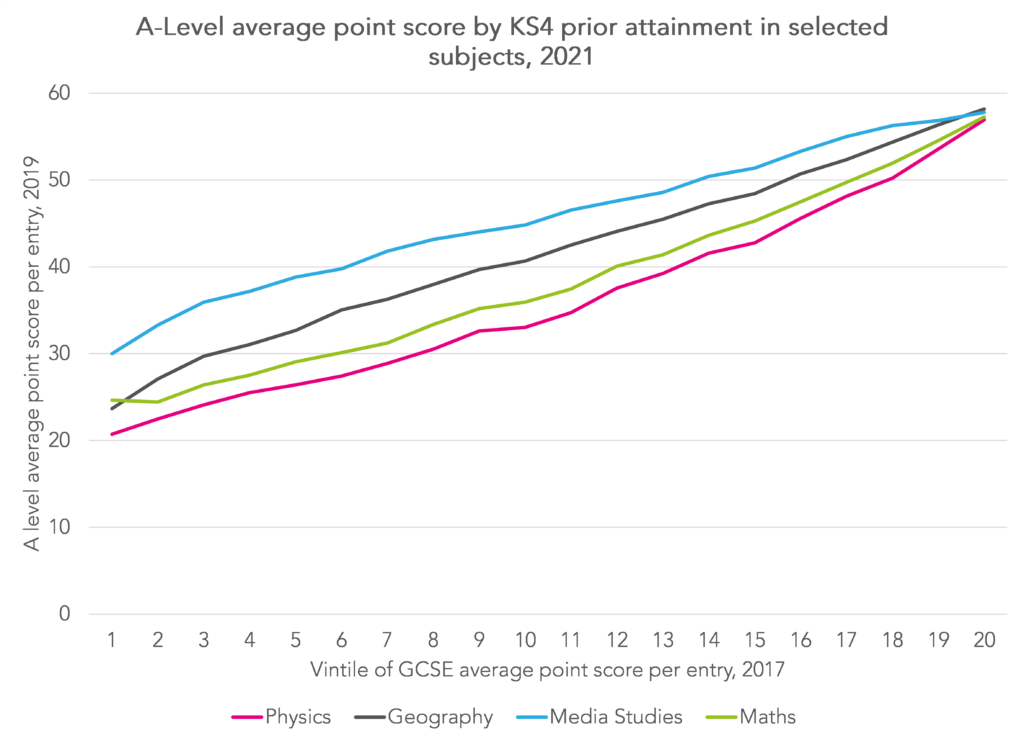

In the chart below, I’ve divided students who entered A-Levels in 2019 into twenty evenly sized bands based on their GCSE average point score in 2017[2]. It shows how the A-Level APS varies in a selection of subjects.

The lines tend to converge among students with very high levels of prior attainment. This suggests their grades tend to be fairly similar.

But at the lower ends of the distribution, there are wide gaps. The line for physics in some places is a whole grade (10 points) lower than geography and a grade and a half (15 points) lower than media studies. And remember here I have only included students who have entered A-Levels, I’ve not included anyone who started an A-Level but dropped out.

Repeating the analysis for 2021, when teacher assessed grades replaced exams, shows that differences between the selected subjects narrowed slightly.

Ofqual’s proposed approach to awarding grades this year will see standards set half way between 2019 and 2021. Consequently, results relative to 2021 will be lower by a greater margin in physics compared to media studies.

Summing up

Students who enter A-Level maths alongside A-Level physics and computer science tend to achieve slightly higher grades than those who don’t enter A-Level maths. This true for all subjects but especially so for physics and computer science where the raw difference is over a grade on average. However, the difference in A-Level attainment reduces to around a third of a grade on average controlling for attainment in GCSE maths.

As some readers pointed out in response to the previous blog, many students will take A-Level maths alongside A-Level physics with one eye on their choice of higher education course. The question might then be whether we want to encourage more young people to take A-Level physics who perhaps might not want to pursue a degree in science or engineering.

We also have to address the question of whether the current grading standards in physics are putting some students off studying it. If you had a decent chance of achieving a higher grade in another subject would you take it?

- A*=60; A=50; B=40; C=30; D=20; E=10; U=0.

- I have not included students who entered GCSEs in previous years

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

I’d love to know if taking Further Maths has a larger impact on Physics A Level grades (controlling for prior attainment)!

How should your ‘vintiles’ be interpreted?

i.e. What sort of GCSE scores would vintile 6 (say) correspond to?

Another bugbear is 3 or 4 A levels. is there an impact due to the ‘time lost’ studying a fourth subject (which usually gets discarded at some point anyway)? Time which could otherwise be put to better use keeping up to speed with three core subjects – especially at the start of Year 12 which most would agree can be a very difficult transition period for many pupils coming to terms with greater independance in their learning.