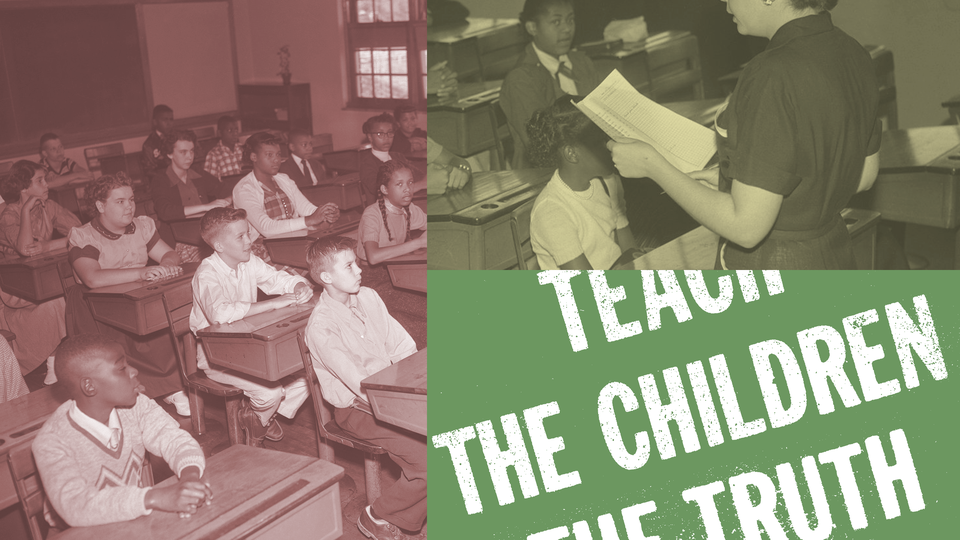

Every effective American teacher seeks the trust of society, of parents, and of the young people they teach. Public education as a whole depends on these bonds of trust. Our divisive politics regarding how to teach children about slavery, race, and other difficult subjects in school has broken that trust.

Anyone who has ever taught for one day knows that trust must be earned. Facing a classroom full of 14- or 16-year-olds with varying degrees of attention and preparation on any subject is one of the hardest and most important of all professions.

What American teachers most need is autonomy, community respect, the right to some creativity within their craft, time to read, and, perhaps above all, support for their intellectual lives. Most would not mind a pay raise.

The last thing teachers need is to contend with what House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has called a “bill of rights for parents.” Such an idea has no relation to reality except as a political wedge. In most education systems in this country, parents are welcome to visit schools at appropriate times, to become involved in extracurricular activities, and to communicate regularly with teachers about their children’s performance. Teachers often beg parents to become engaged with students’ learning.

The curriculum, however, is another matter. Trained teachers, curriculum directors, and school principals are responsible for organizing the content and methods by which a subject such as history is taught. Maintaining parent and community trust in schools’ ability to do this well requires that educators are properly credentialed, that teachers get continued training, and that the best and brightest are getting recruited into teaching. But this trust is now being derailed by the preposterous claim that critical race theory has infested our schools via the secret satchels of radical teachers and their distant, elitist accomplices in university history departments.

For nearly three decades, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History (GLI), and many other institutions, foundations, and agencies, including the federal Education Department, have sponsored summer seminars that bring secondary- and middle-school history instructors to university campuses, where they are treated as professionals and intellectuals. They discover the mysteries and joys of archives and original documents, and they learn through the best scholarship from the people who wrote it. They take seminars about presidential history, the American Revolution, the Civil War and Reconstruction, the Gilded Age, westward expansion, Native American culture and dispossession, gender and women’s history, the civil-rights movement, immigration, urban history, industrialization, constitutional history, and yes, slavery, abolition, and racism as central threads in the American experience.

If Republican politicians and the parents they have disingenuously inflamed need a target for their fears, let them blame the American historians, like me, who spend months of their lives helping teachers build better bases of knowledge about real history. The finest historians of the late 20th and early 21st centuries—far too many to name—have been teaching teachers in classrooms and on field trips bursting with knowledge, sizzling conversations, astonishing documents, and most of all, a hard-earned, even joyous mutual trust.

So let the Republicans blame us. Bring it on. The American Historical Association and the Organization of American Historians have signed on to a coalition of more than 25 such groups called Learn From History, which seeks to combat deliberate misinformation about the current state of history education. This is one history war we have to win.

GLI reports that since 1995, approximately 28,000 teachers have participated in its summer seminars (I’ve taught at least one seminar through this program each summer for more than two decades), as well as in online courses and public lectures. Its website has become an alternative Google for history teachers. The numbers may be even larger for the NEH. Teachers with a passion to improve their game embrace these experiences, learning an inspiring, pluralistic American history; parents and politicians would do well to observe. Come listen to teachers debate the books they read, and wrestle with how to create pedagogical stories about both the darkest and the most uplifting history. Listen to them figure out the balance in their own classrooms between the heroic and the tragic, between war and peace, as they wrestle with how to teach about the changing character of racism, and about the forces of change in history that humans can only hope to withstand, if never control. Come feel their intensity, see them move in and out of the irony of human folly and aspiration, as they confront their own assumptions and beliefs.

Parents and Republican politicians should come listen to serious teachers grapple with the question: What is this thing called “history?” History is not a fable told to make us feel good or bad, not a plaything or a pageant of progress toward some goal of equipoise above the human condition. We are always and everywhere in the middle of history; we cannot escape it. In 1935, W. E. B. Du Bois made a compelling appeal while writing about Reconstruction: “Nations reel and stagger on their way; they make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all of this, so far as the truth is ascertainable?”

Some of the most hopeful moments of my teaching life have come in working with secondary teachers. We are not on the clock, and everyone has temporarily escaped their normal lives to simply learn together in a rare kind of teacherly communion. I was once, after all, one of them. I spent the first seven years of my career as a high-school history teacher in my hometown of Flint, Michigan, in the 1970s. I still maintain that in those years I did the most important teaching of my life. My students were Black, white, and Hispanic, mostly stable working class, and no one left guilty because they were learning about slavery for the first time. My fellow teachers and I blundered our way through curricular revolutions; we were committed simply to offering our students ways to forge a sense of history, of why the past matters, how it has shaped us, whatever the subject. No one owns history, but we are all responsible for it, bound by our humanity to know as much of it as we can.

In his “Talks to Teachers,” a series of lectures delivered in 1899 and 1900, the great American philosopher William James found inspiration in the “fermentation” among secondary-school teachers at the turn of the 20th century, admiring their “searching of the heart about the highest concerns of their profession.” James said the good teacher needed “tact” in “front of pupils,” a good deal of “ingenuity,” and, above all, knowledge of their subjects. “The teachers of this country,” he declared, “have its future in their hands. The earnestness which they at present show in striving to enlighten and strengthen themselves is an index of the nation’s probabilities of advance in all ideal directions.” James trusted teachers as he challenged them. He offered several maxims for teachers, one of which endures in our own historical moment: “Don’t preach too much to your pupils or abound in good talk in the abstract. Lie in wait rather for the practical opportunities, be prompt to seize those as they pass, and thus at one operation get your pupils both to think, to feel, and to do.” Is there a greater purpose for teaching than those three aims? Reaching for those aims, James contended, makes teaching a very high calling.

Trust the teachers. Some will stumble and some will soar. Historians have their backs. If William James could trust teachers in the violent racial, ethnic, and class conflict of 1900, why can’t we today? Is our democracy so broken that we cannot do the same?