The television version of War and Peace, transfixing its BBC audience, comes as an apt reminder that a great story can be like a love affair: an infinite labyrinth of excitement, sorrow and desire.

Tales of love and death aside, what else matters to mankind’s stone-age brain? Set human passions against a backdrop of war and invasion, like solitary figures standing in front of a city in flames, and you have box-office gold. As audiences, our consciousness remains hard-wired with some very primitive storylines.

Tolstoy understood this when, having worked for years on the manuscript he called “1805”, he dramatically retitled it War and Peace. With a single phrase, he met the lasting challenge of any literature: achieving a happy marriage between high art and the low drives of a simple plot. Besides, he always wanted to appeal to a wide audience: “To say that a work of art is good, but incomprehensible to the majority of men, is the same as saying of some kind of food that it is very good but most people can’t eat it.”

Now that Pierre and Natasha are married, and the credits have rolled, is the box set of this ultimate mini-series our only comfort ? What if – the storyteller’s essential question – what if we could be watching “War & Peace Regained”? What might that series look like? Let’s play Fantasy Tolstoy.

It’s not inconceivable that a professional scriptwriting team could take the dramas of Tolstoy’s five families – the Bezukhovs, the Bolkonskys, the Rostovs, the Kuragins and the Drubetskoys – and eke out a sequel. Conceivable, yes, but doomed to inferiority, at best “Millsovich & Boonski on the Steppe”.

Tolstoy himself insisted that War and Peace was “not a novel”, and that he was primarily interested in the interplay of history, philosophy and fate. His book was the product of painstaking research. Although, famously, he liked to play down the role of great men in the historical process, the afterlives of his French and Russian antagonists might provide the raw material for a colourful and enthralling sequel, based in reality. So what about the documentary alternatives ?

General Kutuzov – Prince Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov – the victor of Borodino, idolised by Tolstoy, sadly has no future at the box office. He fell ill and died a few months after the battle, in April 1813. But his master, Tsar Alexander I, offers promising script material. After Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow, the tsar emerged as one of the most powerful figures in the new Europe.

But despite his success, Russia was internally unstable and Alexander I became increasingly paranoid about plots against his throne. Conspiracy theories outlived him. After the tsar’s death from typhus on 1 December 1825, there were persistent rumours, widely believed by Russian peasants, that Alexander had become a monk, and was still alive.

If War and Peace Redux, filmed on location, proved too pricey for a budget-conscious BBC, there could be a Napoleon mini-series shot closer to home. On his return to France, and despite defeat at the battle of Leipzig in 1813, Napoleon continued to outwit the Allies, notably in his escape from Elba and the extraordinary “100 Days” that ensued.

His exile to Longwood House on Saint Helena in 1815 has inspired many novelists and playwrights to explore the tragic ignominy of the emperor’s final years. Later this spring, indeed, the renowned Australian novelist Thomas Keneally, author of Schindler’s List, will publish Napoleon’s Last Stand, a high-spirited account of the emperor’s unlikely friendship with a rebellious English girl and her family.

Longwood, however, is not (the Bolkonskys’) Bald Hills, and the War and Peace audience still craves Mother Russia – snow, sledges, seduction and samovars. In the hunt for a sequel, Fantasy Tolstoy should, perhaps, look again at the author, not his characters. Tolstoy might give us Russia, in a highly modern way. There are successful precedents for the fictional exploration of Tolstoy’s life.

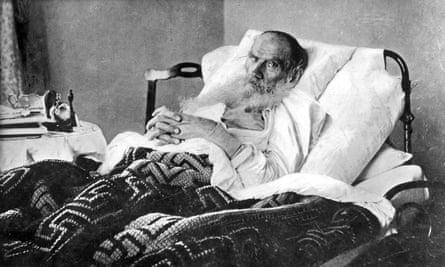

The Last Station (2009) starred Helen Mirren and Christopher Plummer in a moving dramatisation of Tolstoy’s extraordinary death at Astapovo railway station, written and directed from a novel by Jay Parini. Parini’s version plays with the idea that the facts of a writer’s life can be every bit as absorbing as his fiction.

Last week, in an interview with the Observer, Parini elaborated this point. “Tolstoy had already imagined his own death, of course, in The Death of Ivan Illych in 1886. That was 24 years before he finally hit the road, abandoning his wife of many decades, dying in a railway station in a remote corner of Russia.” Parini sees Tolstoy compulsively morphing fact and fiction. “He essentially became Pierre, and his experiences of war in the Crimea – just read his amazing Sevastopol stories – inform the battlefield vividness of War and Peace.”

Parini believes that the fusion of fact and fiction is a characteristic of the Victorian age. “Like Dickens, Tolstoy became each and every character he wrote. So he is also Prince Andrei: one can’t miss that version of his idealised self. He was the crazy warrior of the Crimea: he had fought hard in Sevastopol. But he was also strikingly modern – a founding father in the movement for non-violent resistance, the man who inspired Gandhi and Martin Luther King.”

Addressing Tolstoy’s idealism, Parini also notes that Pierre lives on in the older Tolstoy. “One gets a sense of a deep spiritual longing in Pierre, including his almost mystical attachment to the land and the peasants who work the land. Tolstoy was himself imagining his own future, where he would eventually convert to his own idiosyncratic version of Christianity. If you want to see what becomes of Pierre and Natasha, just look to Levin and Kitty in his next big novel, Anna Karenina.”

For Parini, Tolstoy and his books are one. “Tolstoy seemed to embody every aspect of life, trying out all the parts in succession. It was a strange life, but someone had to live it. In the end, Tolstoy even becomes old Kutusov, the wise man on the battlefield of life.”

Parini believes that Tolstoy has the potential to be a promising subject for contemporary TV: he’s a man both of another age and of our own times. Anticipating later cinematic effects, he brought a new consciousness to the novel, a narrative structure noted for its quasi-cinematic point of view, in which the novelist plays God.

“More than anyone of his era,” Parini observes, “Tolstoy seemed to understand the sweep of a camera, panning a battlefield. He knew how to move up close, focus on a scene: a young man charging with a sword, a young woman dying in childbirth. He understood both the close-up and the long shot. There often seems to be a helicopter shooting the landscape at Borodino. The writer’s eye seems to sit on top of a dolly at times, to move easily from point to point. I think it’s the pacing, too, that is preternaturally cinematic: a film is made of short scenes, with quick cuts. Tolstoy gets this, or anticipated (unconsciously) the modern way of viewing the world.”

So, in the game of Fantasy Tolstoy, does Parini have any suggestions for who could play the role of the novelist? “When Tolstoy is writing War and Peace, one needs a young blood, ready to write 10 paragraphs, mow a field, mate with a servant girl and talk philosophy with the countess. I think Clive Owen might work. He has that slightly off-centre rakishness perfect for our Leo.” He pauses. “I’d also cast Robert Downey Jr as Tolstoy in a heartbeat. The barely contained energy and even madness, the sexual liminality! He always seems ready to pounce and hate himself afterwards.”

WHAT THEY DID NEXT

Kutuzov For his victory at the battle of Borodino, Alexander I gave Prince Mikhail Kutuzov the rank of field marshal, and he was later further celebrated for his defeat of French forces at Smolensk in November 1812. But early in 1813, Kutuzov fell ill; he died on 28 April at Bunzlau, Silesia, now Bolesławiec, Poland, aged 67. Ironically, as he had no male heir, his estates passed to the Tolstoy family, because his eldest daughter, Praskovia, had married Matvei Fedorovich Tolstoy. The novelist Leo Tolstoy is said to have idolised Kutuzov.

Alexander I The fall of Napoleon left the tsar one of the most powerful rulers in Europe. After the Congress of Vienna, which ran from September 1814 to June 1815, Alexander became increasingly paranoid about plots against his throne. In the autumn of 1825, while travelling in the south of Russia, he caught typhus and died on 1 December. However, rumours circulated for years that Alexander had not died but had instead become a monk. His handwriting was shown to match that of the monk Feodor Kuzmich, who appeared mysteriously in Siberia in 1836 and was noted for his genteel manner, his command of several languages, and his claim to have forgotten his past.

Napoleon Napoleon never ceased to live in extreme jeopardy, and to defy narrative conventions. He was always a titanic character. The emperor completed his flight from Moscow in December 1812. Soon after, in 1813, Prussia and Austria joined Russian forces in a coalition against France. A chaotic military campaign culminated in a large allied army defeating Napoleon at the battle of Leipzig in October. The following year, the allies captured Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate in April. He was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba, escaped, was defeated at Waterloo and died a prisoner on the island of Saint Helena in 1821.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion