“Termites of the Sea” Found Munching Wood Near Arctic Shipwrecks

The shipworms found in Svalbard may signal an expansion due to ocean warming or be a new species

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/bb/a7bbc228-2a30-4319-8db3-f502dc3eaeee/unnamed-8.jpg)

Øyvind Ødegård spends a lot of time around very cold water, looking for the remains of well-preserved shipwrecks along the coastlines of central Norway and in the Baltic Sea. One thing he never hopes to see are shipworms, long slimy creatures with an insatiable appetite for wood.

So the discovery last month of an enormous timber filled with them—in a place much farther north than they’d ever been found—now has Ødegård wondering if the wrecks’ days are numbered. As first reported last week in Science, the crew of the research vessel Helmer Hanssen was plying Arctic waters when they hauled up a 21-foot log loaded with the mollusks, which are so efficient at tunneling their way through wood that they can annihilate an entire ship in a matter of years.

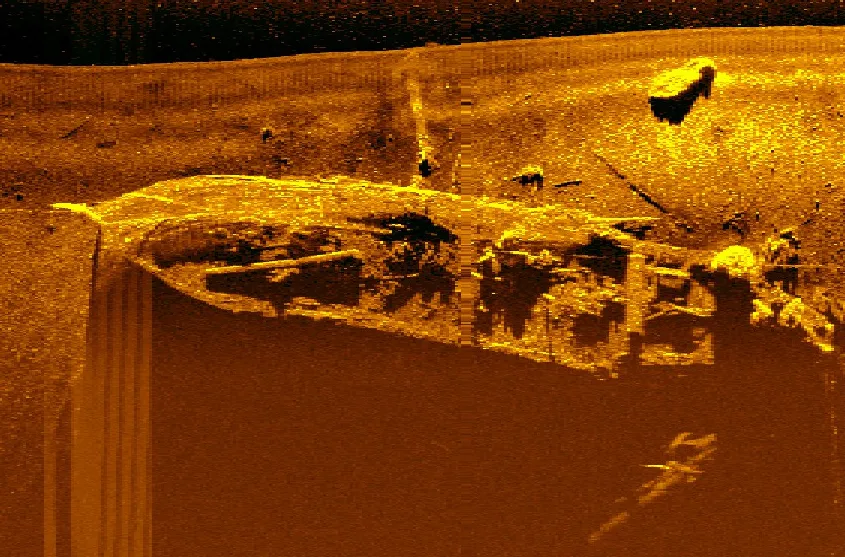

As a marine archaeologist with the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Ødegård has been using semi-autonomous marine robots to look for wrecks near Svalbard, a remote, treeless collection of islands near the high Arctic. There he hopes to find and study as many of the hundreds, possibly thousands, of 17th-century European whaling wrecks, casualties of fighting and the crushing polar ice.

In good conditions, the frigid temperatures help protect Ødegård’s study subjects from archaeological bogeymen, including microbes and shipworms. Ships should remain preserved for hundreds of years with little evidence of decay, so Ødegård had expected that Svalbard would be a benign environment for the wrecks. “I was surprised and quite depressed to find these creatures so far north," he says. "If there’s a climate dimension, things could be deteriorating faster than we thought.”

Investigation last September on the wreck of the whale-oil processing ship Figaro showed limited evidence of shipworms—but the ship lies in a fjord on Svalbard’s western coast that is regularly flushed with warm Gulf Stream waters.

“Our theory was that with warmer temperatures, the coast exposed to Atlantic waters could see an increase in the presence of shipworms with time,” Ødegård says. “We could see evidence of the presence of shipworm, but it was very limited. The wreck we found [the Figaro] is in very good condition.”

Then in January, Jørgen Berge, a marine biologist at the University of Tromsø, was trawling for bottom-dwelling fish on the Helmer Hanssen on the north side of the northernmost island of Svalbard. That's when the team snagged the worm-filled log. Such driftwood is fairly common, arriving from elsewhere on currents, but finding the shipworms took both the crew and scientists aback because this area is flushed with cold Arctic water.

“Then of course, the story changed quite a bit,” Berge says. “In the high Arctic, in a cold fjord, it was far from where we’d expect to find such a species.”

Jutting narrowly northwards past the west coast of Norway and curling up towards the lonely Svalbard archipelago, the Spitzbergen current of the Atlantic Gulf Stream carries the remains of warm water from the south before circling past Greenland. Berge’s first thought was that the shipworms came on the current as hitchhikers, except the larvae in the log were at various stages of development. That meant they’d been there for some time.

The origin of the log and the shipworms’ identity are still under investigation. So far, it’s not known whether they’re a previously unidentified species, or if they are a southern species that has been able to expand their range northward because of warming water.

The shipworms wouldn’t be the first harbinger of a warming trend around the archipelago. Blue mussels, which can’t survive in very cold water, thrived on the archipelago during a warming period that began somewhere around 10,500 years ago. They winked out during the Viking age, when global temperatures dipped. In 2004, Berge discovered they’d again returned to Svalbard after a 1,000-year hiatus.

Mackerel have expanded their range to include Svalbard, as have herring and haddock, other species formerly found much further to the south. Atlantic cod, too, have made their way to the Arctic, challenging the native polar cod for space and resources.

“Working in the high Arctic, you get the first signal of how a changing, warming climate is affecting the biological environment,” Berge says. “For some species, it may be a battle on two fronts.”

For Berge, the discovery of shipworms represents a bit of a double-edged sword: intrigue at the possibility of a new endemic species of Arctic shipworm, and consternation that if it is a new species, it’s only been spotted because previously ice-locked regions are becoming more accessible due to warming.

“Before we can say anything about what sort of threat this might be, we simply need to know what we’re dealing with,” Berge said. “But as the Arctic oceans open up and have less and less sea ice, we’re likely to get more new discoveries about the ocean that until now have remained more or less off-limits. Our knowledge of the central Arctic Ocean is extremely limited.”

Ødegård seems resigned to the possibility that the outlook for underwater cultural heritage might not be so cheery under either circumstance. A new species could move southward and hit up wrecks. Southern species migrating northward in warming waters could do the same. And with an increase in shipping traffic as the oceans become more reliably ice-free, other organisms released from ballast water could potentially become established as well.

Still, because so much is still not known about whether climate is to blame and whether the worm is a newfound species, Berge is reluctant to cast the find in a hard light.

“I don’t think it’s a one-off find, certainly not,” he adds. “But my gut feeling is that once we get more data and insight, this will be a different kind of story.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)