This article was peer reviewed by Moritz Kröger, Bruno Mota and Vildan Softic. Thanks to all of SitePoint’s peer reviewers for making SitePoint content the best it can be!

Before we dive into the topic we have to answer the crucial question: What is reactive programming? As of today, the most popular answer is that reactive programming is programming with concurrent data streams. Most of the time we will find the word concurrent replaced by asynchronous, however, we will see later on that the stream does not have to be asynchronous.

It is easy to see that the “everything is a stream” approach can be applied directly to our programming problems. After all, a CPU is nothing more than a device which processes a stream of information consisting of instructions and data. Our goal is to observe that stream and transform it in case of particular data.

The principles of reactive programming are not completely new to JavaScript. We already have things like property binding, the EventEmitter pattern, or Node.js streams. Sometimes the elegance of these methods comes with decreased performance, overly complicated abstractions, or problems with debugging. Usually, these drawbacks are minimal compared to the advantages of the new abstraction layer. Our minimal examples will, of course, not reflect the usual application, but be as short and concise as possible.

Without further ado, let’s get our hands dirty by playing with The Reactive Extensions for JavaScript (RxJS) library. RxJS uses chaining a lot, which is a popular technique also used in other libraries such as jQuery. A guide to method chaining (in the context of Ruby) is available on SitePoint.

Stream Examples

Before we dive into RxJS we should list some examples to work with later. This will also conclude the introduction to reactive programming and streams in general.

In general, we can distinguish two kinds of streams: internal and external. While the former can be considered artificial and within our control, the latter come from sources beyond our control. External streams may be triggered (directly or indirectly) from our code.

Usually, streams don’t wait for us. They happen whether we can handle them or not. For instance if we want to observe cars on a road, we won’t be able to restart the stream of cars. The stream happens independent of if we observe it or not. In Rx terminology we call this a hot observable. Rx also introduces cold observables, which behave more like standard iterators, such that the information from the stream consists of all items for each observer.

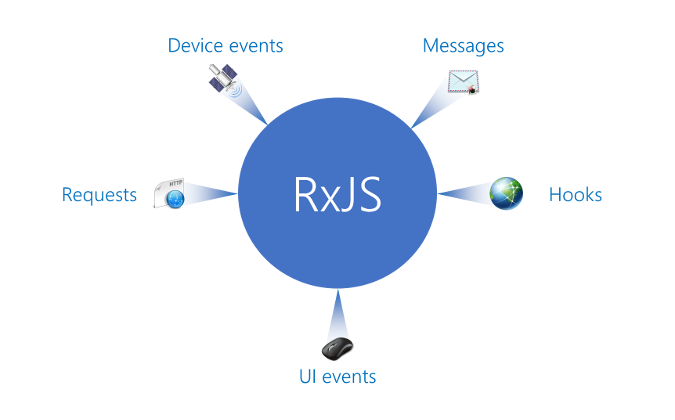

The following images illustrates some external kinds of streams. We see that (formerly started) requests and generally set up web hooks are mentioned, as well as UI events such as mouse or keyboard interactions. Finally, we may also receive data from devices, for example GPS sensors, an accelerometer, or other sensors.

The image also contained one stream noted as Messages. Messages can appear in several forms. One of the most simple forms is a communication between our website and some other website. Other examples include communication with WebSockets or web workers. Let’s see some example code for the latter.

The code of the worker is presented below. The code tries to find the prime numbers from 2 to 1010. Once a number is found the result is reported.

(function (start, end) {

var n = start - 1;

while (n++ < end) {

var k = Math.sqrt(n);

var found = false;

for (var i = 2; !found && i <= k; ++i) {

found = n % i === 0;

}

if (!found) {

postMessage(n.toString());

}

}

})(2, 1e10);

Classically, the web worker (assumed to be in the file prime.js) is included as follows. For brevity we skip checks for web worker support and legality of the returned result.

var worker = new Worker('prime.js');

worker.addEventListener('message', function (ev) {

var primeNumber = ev.data * 1;

console.log(primeNumber);

}, false);

More details on web workers and multi-threading with JavaScript can be found in the article Parallel JavaScript with Parallel.js.

Considering the example above, we know that prime numbers follow an asymptotic distribution among the positive integers. For x to ∞ we obtain a distribution of x / log(x). This means that we will see more numbers at the beginning. Here, the checks are also much cheaper (i.e., we receive much more prime numbers per unit of time in the beginning than later on.)

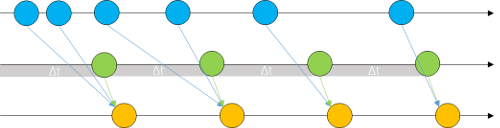

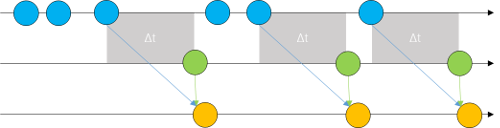

This can be illustrated with a simple time axis and blobs for results:

A non-related but similar example can be given by looking at a user’s input to a search box. Initially, the user may be enthusiastic to enter something to search for; however, the more specific his request gets the greater the time difference between the key strokes becomes. Providing the ability to show live results is definitely desirable, to help the user in narrowing his request. However, what we do not want is to perform a request for every key stroke, especially since the first ones will be performed very fast and without thinking or the need to specialize.

In both scenarios the answer is to aggregate previous events over a given time interval. A difference between the two described scenarios is that the prime numbers should always be shown after the given time interval (i.e., some of the prime numbers are just potentially delayed in presentation). In contrast, the search query would only trigger a new request if no key stroke happened during the specified interval. Therefore, the timer is reset once a key stroke has been detected.

RxJS to the Rescue

Rx is a library for composing asynchronous and event-based programs using observable collections. It is well known for its declarative syntax and composability while introducing an easy time handling and error model. Thinking of our former examples we are especially interested in the time handling. Nevertheless, we will see there is much more in RxJS to benefit from.

The basic building blocks of RxJS are observables (producers) and observers (consumers). We already mentioned the two types of observables:

- Hot observables are pushing even when we are not subscribed to them (e.g., UI events).

- Cold observables start pushing only when we subscribe. They start over if we subscribe again.

Cold observables usually refer to arrays or single values that have been converted to be used within RxJS. For instance, the following code creates a cold observable that only yields a single value before completing:

var observable = Rx.Observable.create(function (observer) {

observer.onNext(42);

observer.onCompleted();

});

We may also return a function containing cleanup logic from the observable creation function.

Subscribing to the observable is independent of the kind of observable. For both types we can provide three functions that fulfill the basic requirement of the notification grammar consisting of onNext, onError, and onCompleted. The onNext callback is mandatory.

var subscription = observable.subscribe(

function (value) {

console.log('Next: %s.', value);

},

function (ev) {

console.log('Error: %s!', ev);

},

function () {

console.log('Completed!');

}

);

subscription.dispose();

As a best practice we should terminate the subscription by using the dispose method. This will perform any required cleanup steps. Otherwise, it might be possible to prevent garbage collection from cleaning up unused resources.

Without subscribe the observable contained in the variable observable is just a cold observable. Nevertheless, it is also possible to convert it to a hot sequence (i.e., we perform a pseudo subscription) using the publish method.

var hotObservable = observable.publish();

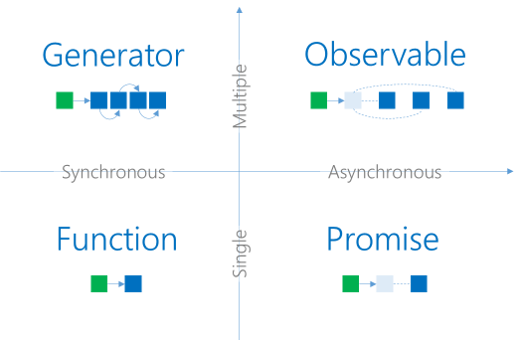

Some of the helpers contained in RxJS only deal with conversion of existing data structures. In JavaScript we may distinguish between three of them:

- Promises for returning single asynchronous results,

- Functions for single results, and

- Generators for providing iterators.

The latter is new with ES6 and may be replaced with arrays (even though that’s a bad substitute and should be treated as a single value) for ES5 or older.

RxJS now brings in a datatype for providing asynchronous multiple (return) value support. Therefore, the four quadrants are now filled out.

While iterators need to be pulled, the values of observables are pushed. An example would be an event stream, where we cannot force the next event to happen. We can only wait to be notified by the event loop.

var array = [1,2,3,4,5];

var source = Rx.Observable.from(array);

Most of the helpers creating or dealing with observables also accept a scheduler, which controls when a subscription starts and when notifications are published. We won’t go into details here as the default scheduler works just fine for most practical purposes.

Many operators in RxJS introduce concurrency, such as throttle, interval, or delay. We will now take another look at the previous examples, where these helpers become essential.

Examples

First, let’s take a look at our prime number generator. We wanted to aggregate the results over a given time, such that the UI (especially in the beginning) doesn’t have to deal with too many updates.

Here, we actually might want to use the buffer function of RxJS in conjunction with the previously mentioned interval helper.

The result should be represented by the following diagram. The green blobs arise after a specified time interval (given by the time used to construct interval). A buffer will aggregate all the seen blue blobs during such an interval.

Furthermore, we could also introduce map, which helps us to transform data. For instance, we may want to transform the received event arguments to obtain the transmitted data as a number.

var worker = new Worker('prime.js');

var observable = Rx.Observable.fromEvent(worker, 'message')

.map(function (ev) { return ev.data * 1; })

.buffer(Rx.Observable.interval(500))

.where(function (x) { return x.length > 0; })

.map(function (x) { return x.length; });

The fromEvent function constructs an observable from any object using the standard event emitter pattern. The buffer would also return arrays with zero-length, which is why we introduce the where function to reduce the stream to non-empty arrays. Finally, in this example we are only interested in the number of generated prime numbers. Therefore we map the buffer to obtain its length.

The other example is the search query box, which should be throttled to only start requests after a certain idle time. There are two functions that may be useful in such a scenario: The throttle function yields the first entry seen within a specified time window. The debounce function yields the last entry seen within a specified time window. The time windows are also shifted accordingly (i.e., relative to the first / last item).

We want to achieve a behavior that is reflected by the following diagram. Hence, we’re going to use the debounce mechanism.

We want to throw away all the previous results and only obtain the last one before the time window depleted. Assuming that the input field has the id query we could use the following code:

var q = document.querySelector('#query');

var observable = Rx.Observable.fromEvent(q, 'keyup')

.debounce(300)

.map(function (ev) { return ev.target.value; })

.where(function (text) { return text.length >= 3; })

.distinctUntilChanged()

.map(searchFor)

.switch()

.where(function (obj) { return obj !== undefined; });

In this code the window is set to 300ms. Also we restrict queries for values with at least 3 characters, which are distinct from previous queries. This eliminates unnecessary requests for inputs that have just been corrected by typing something and erasing it.

There are two crucial parts in this whole expression. One is the transformation of the query text to a request using searchFor, the other one is the switch() function. The latter takes any function which returns nested observables and produces values only from the most recent observable sequence.

The function to create the requests could be defined as follows:

function searchFor(text) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open('GET', apibaseUrl + '?q=' + text, true);

xhr.send();

return Rx.Observable.fromEvent(xhr, 'load').map(function (ev) {

var request = ev.currentTarget;

if (request.status === 200) {

var response = request.responseText;

return JSON.parse(response);

}

});

}

Note the nested observable (which might result in undefined for invalid requests) which is why we’re chaining switch() and where().

Conclusions

RxJS makes reactive programming in JavaScript a joyful reality. As an alternative there is also Bacon.js, which works similarly. Nevertheless, one of the best things about RxJS is Rx itself, which is available on many platforms. This makes the transition to other languages, platforms, or systems quite easy. It also unifies some of the concepts of reactive programming in a set of methods that are concise and composable. Furthermore, several very useful extensions exist, such as RxJS-DOM, which simplifies interaction with the DOM.

Where do you see RxJS shine?

Frequently Asked Questions about Functional Reactive Programming with RxJS

What is the difference between Functional Programming and Functional Reactive Programming?

Functional Programming (FP) and Functional Reactive Programming (FRP) are both programming paradigms, but they have different focuses. FP is a style of programming that treats computation as the evaluation of mathematical functions and avoids changing-state and mutable data. It emphasizes the application of functions, in contrast to the imperative programming style, which emphasizes changes in state.

On the other hand, FRP is a variant of FP that deals with asynchronous data streams. It combines the reactive programming model with functional programming. In FRP, you can express static (e.g., arrays) and dynamic (e.g., mouse clicks, web requests) data streams and react to their changes.

How does RxJS fit into Functional Reactive Programming?

RxJS (Reactive Extensions for JavaScript) is a library for reactive programming using Observables, to make it easier to compose asynchronous or callback-based code. This makes it a perfect fit for Functional Reactive Programming. With RxJS, you can create data streams from various sources and also transform, combine, manipulate, or react to these data streams using its provided operators.

What are Observables in RxJS?

Observables are a core concept in RxJS. They are data streams, which can emit multiple values over time. They can emit three types of values: next, error, and complete. The ‘next’ values can be any JavaScript object, ‘error’ is an error object when something goes wrong, and ‘complete’ doesn’t have any value, it just signals that the observable won’t emit any more values.

How do I handle errors in RxJS?

RxJS provides several operators to handle errors, such as catchError and retry. The catchError operator catches the error on the source Observable and continues the stream with a new Observable or an error. The retry operator resubscribes to the source Observable when it fails.

What are Operators in RxJS?

Operators are pure functions that enable a powerful functional programming style of dealing with collections with operations like ‘map’, ‘filter’, ‘concat’, ‘reduce’, etc. There are dozens of operators available in RxJS that can be used to handle complex manipulations of collections, whether they are arrays of items, streams of events, or even promises.

How can I test my RxJS code?

RxJS provides testing utilities, such as TestScheduler, which makes testing asynchronous code easier. You can also use marble diagrams for visualizing Observables during testing.

Can I use RxJS with Angular?

Yes, RxJS is actually a key part of Angular. It’s used in the HTTP module of Angular and also in the EventEmitter class which is used for custom events.

What is the difference between Promises and Observables?

Promises and Observables both deal with asynchronous operations, but they do it in different ways. A Promise is a value that may not be available yet. It can be resolved (fulfilled or rejected) only once. On the other hand, an Observable is a stream of values that can emit zero or more values, and it can be subscribed to or unsubscribed from.

How can I unsubscribe from an Observable?

When you subscribe to an Observable, you get a Subscription object. You can call the unsubscribe method on this object to cancel the subscription and stop receiving data.

What are Subjects in RxJS?

Subjects in RxJS are a special type of Observable that allows values to be multicasted to many Observers. Unlike plain Observables, Subjects maintain a registry of many listeners.

Florian Rappl

Florian RapplFlorian Rappl is an independent IT consultant working in the areas of client / server programming, High Performance Computing and web development. He is an expert in C/C++, C# and JavaScript. Florian regularly gives talks at conferences or user groups. You can find his blog at florian-rappl.de.