Gun Deaths May Not Eclipse Traffic Fatalities Just Yet

New data shows a mysterious surge in the number of people killed in motor-vehicle accidents.

A grim turning point, long expected, may not have arrived in 2015 after all.

Public-health officials and statisticians had pinpointed last year as the year that gun deaths would likely surpass traffic fatalities in the United States.

But the latest projections from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration paint a different picture, one that’s no less disturbing. New data shows traffic deaths jumped by more than 9 percent during the first nine months of 2015, the most recent period for which information is available. What that means: More than 2,000 additional people died in traffic accidents in the United States compared with the same period the year before.

The latest numbers suggest cars were on pace to kill nearly 36,000 people in 2015, significantly more than the 32,675 traffic deaths in 2014.

Firearms, meanwhile, killed 33,599 people in 2014, the most recent year for which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has data. Experts had expected traffic deaths to dip below 33,000 last year, but that now appears unlikely. The NHSTA says it’s too soon to speculate on factors contributing to the “significantly higher” traffic fatality rates last year.

Lower gas prices are one possible reason. When gasoline is cheaper, people drive more—and more time on the road translates into more fatal accidents. That may help begin to explain what happened last year, but only partially. Americans logged about 80 billion extra miles in the first nine months of last year, a 3.5-percent increase compared with the year before. But traffic deaths went up by 9 percent. (We won’t know how many people were killed in motor-vehicle accidents throughout all of 2015 until next fall, when the final federal data is released.)

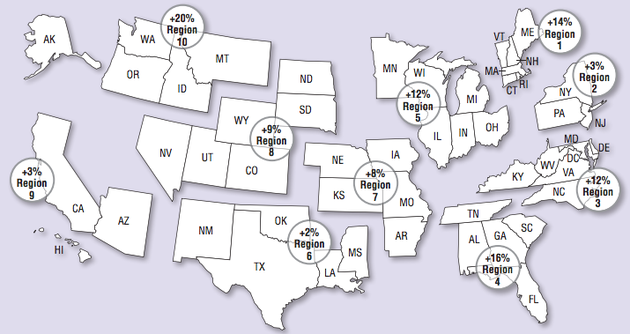

The situation also looks a bit different when you assess the numbers on a regional level—though because some of the NHSTA’s designated regions span great distances, it’s difficult to elucidate why. For instance, the increase in traffic deaths exceeded 20 percent in the region that includes Alaska, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana, but only went up by about 3 percent in the region that includes California, Arizona, Hawaii, and other Pacific territories.

This table shows the percentage change in estimated traffic fatalities from 2014 to 2015, by region:

Looking at gun deaths and motor-vehicle deaths together may seem a kind of non-sequitur, but it’s also a way of assessing the risks associated with “two national icons,” as The Economist put it last year. America’s most beloved technologies—guns and cars—are also its deadliest.

But while car-safety technology has improved dramatically in recent decades, handguns have barely changed in a century.

Among those who advocate for stricter gun laws, the threshold at which gun deaths surpass traffic deaths nationwide has been a symbolic turning point—a way to underscore the need for improved gun safety. But in many states, that line has already been crossed. Gun deaths surpassed motor-vehicle deaths in 21 states plus the District of Columbia in 2014, according to analysis by the Violence Policy Center. (The states where gun fatalities outpaced traffic deaths in that year: Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, District of Columbia, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.)

Other statistics are just as stark: Some 600 children under the age of 12 have been killed by firearms in the United States since the Sandy Hook massacre, and possibly many more than that, according to analysis by NBC News. “We are the only advanced country on earth that sees this kind of mass violence erupt with this kind of frequency,” President Barack Obama said in a speech at the White House last month. “Somehow we’ve become numb to it, and we start thinking that this is normal.”

You don’t need to look very hard to know there is a problem.