LONDON—I’m a stalker. Not a virtual stalker, a real life stalker. The good news is that Douglas Coupland—author of Microserfs and Generation X—doesn’t seem to mind.

Snatching my camera, Coupland reassures me in his smooth Canadian brogue that “electrons are free, one of these has to be OK.” He then fires off 20 selfies, while I stand here in shock.

This may be somewhat at odds with the art that he's here to promote at the hot new Whitechapel Gallery exhibition, Electronic Superhighway (2016-1966), which has just opened to the public in London. Coupland's large mixed media pieces are black and white photos with Piet Mondrian-like coloured cubes or black and white stripes stuck over them. Titled Deep Face, the images (see gallery below) represent a critique of Facebook’s face recognition software.

But now I can live happy in the knowledge that the celebrated Canadian author and I are—at last—sharing the same electrons. His novels stand alongside William Gibson’s 1984 Neuromancer as the books that allowed me to make sense of the technological cultural shift that happened during my teens.

My surprise slew of celebrity selfies seems to unconsciously mirror the paradigm of this exhibit. Kim Kardashian’s derrière broke the Internet last year, so somehow I'm not shocked to be greeted with large buttocks as I enter the gallery. This 2015 work by Swiss-born artist Olaf Breuning, entitled Text Butt, introduces what seems to be a central theme surrounding the relationship of technology and the body. But(t) it also offers the viewer an insight into surveillance, suggesting that digital information can be both empowering and isolating.

The show—featuring over 100 works by 70 artists—is curated by Omar Kholeif, who flips chronology on its head.

-

Deep Face 2015 by Douglas CouplandWhitechapel Gallery

-

Loading 2007 by Aristarkh ChernyshevLucy Orr

-

Untitled DickPic 2015 by Celia Hempton, who paints Chatroulette participantsLucy Orr

-

Glowing Edges-7.10 2014 by Constant DullaartLucy Orr

-

Plastic Wrap 2014 by Constant DullaartLucy Orr

-

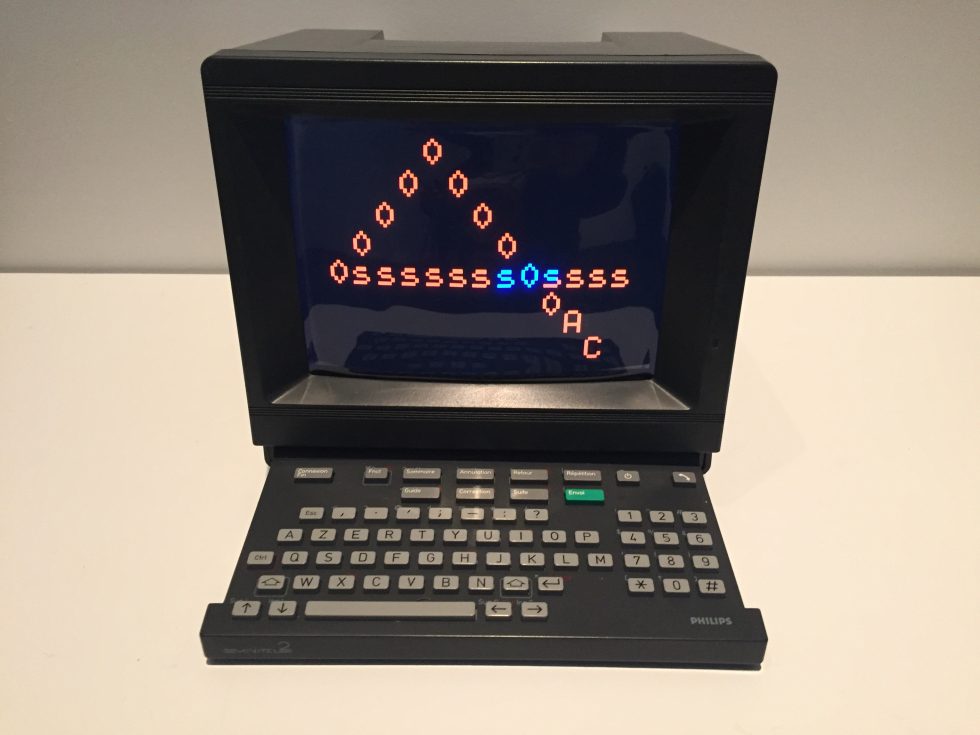

Internet Dream 1994 by Nam June Paik

-

My Generation 2010 by Eva and Franco MattesLucy Orr

-

En Plein Air: Music of Objective Romance 2015 by Jacolby SatterwhiteLucy Orr

-

En Plein Air: Music of Objective Romance 2015 by Jacolby SatterwhiteLucy Orr

-

Text Butt 2015 by Olaf BreuningLucy Orr

-

Autonomy Cube 2014 by Trevor Paglen and Jacob Appelbaum.Lucy Orr

The first gallery is an accelerated gaze into the personal becoming public. I'm especially taken by the dashed-out, expressive artwork of Celia Hempton. Her paintings were daubed while holding conversations with anonymous individuals on Chatroulette—and their names are the titles of the pieces. I'm reminded of many drunken parties that involved shrieks of laughter as we watched someone masturbating at us on an iPad screen. Then it seemed like a game, but these small canvases—heavy with faceless brush strokes—suggest something more sinister.

As I round a corner, my eye is caught by a video installation of a predatory uterus shooting laser beams at a man cloaked in a superhero costume standing on a beach. Prolific NYC artist Jacolby Satterwhite’s psychedelic, pornographic, and physically impossible surreal animation/video installation En Plein Air: Music of Objective Romance 2015 reminds me of a One Dot Zero project or a Mapping Festival installation. It's a critique of traditional male/female, passive/aggressive romantic narratives that regularly pop up in anime. Apparently, it's also a portentous piece on climate change.

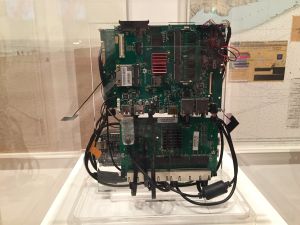

Artist Trevor Paglen and security researcher Jacob Applebaum’s Autonomy Cube 2014, constructed to be seen and used, is bewitching. The clear plastic sculpture contains several Internet-connected computers, which create an open Wi-Fi hotspot. Anyone can join the wireless network, and it routes all traffic to Tor. Once in, I become integrated into an artist statement on privacy and virtual anonymity, but luckily it's in no way reminiscent of the 1997 Canadian B-movie Cube.

Instantly recognisable across the room (courtesy of my years as a designer) is the first ever image to be Photoshopped in 1987, titled Jennifer in Paradise. Conceptual artist Constant Dullaart found during his research for this piece that the original image had been lost through replication and manipulation. He uses the image to explore representation by looping the picture back through random and culturally clichéd Photoshop filters.

Walking to the second floor, I am met on the stairs by Aristarkh Chernyshev’s Loading 2007 circular LED sign—which is clearly a satirical dig at our obsession with information.

Especially given the diversity controversy surrounding the Oscars this year, it suddenly hits me that—even though I've navigated my way through lavishly multicultural Brick Lane to get here—the gallery is full of white faces peering at the works by artists such as Mendi and Keith Obadike, whose Blackness for Sale 2001 (a listing for blackness on eBay) is itself an aspect of the art world that should be opened to scrutiny and criticism.

Next, I find myself gazing at the work of the father of video art, Korean American Nam June Paik, who is credited with the initial usage of the phrase “electronic superhighway." His video sculpture, Internet Dream 1994, occupies a whole wall and most of my peripheral vision. The 52 flashing screens of electronically processed images—clearly intended to elicit viewer participation—are captivating, and they appeal much more to me than Paik's electro-acoustic collaboration in the group Fluxus with John Cage.

Moving even further back in time, Vuk Ćosić’s ASCII: A History of Moving Images 1998 reminds me of my childhood as a MUD crawler and the ASCII dragons who would very slowly scroll down my screen if I took a wrong turn.

Hypnotic, coloured kinetic lights enhance Peter Sedgley's Corona 1970 and Light Pulse no. 3 1968. These huge glowing orbs remind of me of film director Stanley Kubrick’s HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey. They stare menacingly out of the canvas, offering the perfect visual juxtaposition to the detailed circuit board paintings of Ulla Wiggen's, such as TRASK 1967, with its neatly representational lines of capacitors and resistors.

Walking into the final gallery, I'm transported straight to the pages of the Industrial Culture Handbook, published by RE/Search. Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T), founded in 1966, was an interdisciplinary group that collaborated with members such as graphic artist Robert Rauschenberg and physicist Manfred. R. Schroeder. Their performances evolved into the profound thought behind many of the works on hacking, software, surveillance, consumerism, and identity on display at the beginning of Electronic Superhighway.

The copious breadth of the work, and its coverage of constantly evolving platforms with which to explore the symbiosis of technology and art, make this exhibition a valid and extraordinary must-see.

After traversing the realms of the visceral and virtual, I’m feeling peckish. So it’s back to the future as I retrace my steps to the exit to gobble some carrot cake... and continue my stakeout of Douglas Coupland.

Electronic Superhighway (2016-1966) is on from now until May 15 at London's Whitechapel Gallery. Tickets cost £11.95.

* * *

Lucy Orr grew up close to CERN and Fermilab, while her father was busy searching for the Higgs boson (which he eventually found). While waiting for her mutant powers to manifest, Lucy kept herself occupied programming BASIC, reading comics, and playing MUDs. With an extensive career in digital art and animation, she still finds time to pet ferrets, listen to pop punk, and drink cider.

reader comments

22